|

| Nicholas Butler of the USDA NRCS Soil Science Division discussed forest stand improvement practices, the relationship of tree species in the woodlot to soil profiles, and the Ecological Site Survey (similar to the Web Soil Survey) that USDA is developing. English photo |

By Katy Green, Kacey Weber and Jean English

In 2016, MOFGA cosponsored four Conservation Farm Tours with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and local Soil and Water Conservation Districts to highlight conservation strategies used on Maine farms and woodlots. Each tour focused on a specific conservation theme and showed how farmers manage their land to support soil health, wildlife and the natural environment. The tours, which will continue in 2017, are supported by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under number 69-3A75-16-012.

We reported on the workshop and tour of Eli Berry’s Washington, Maine, woodlot and farm in the fall 2016 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer and Gardener. Here we report on the conservation forestry tour of the Brochu Homestead held in Dover-Foxcroft in June 2016.

The Brochus purchased their Bear Hill Road property in 2010. About half the land is in fields and half is forested.

During the tour, Kirby Ellis of Ellis Forest Management and Nicholas Butler of the USDA NRCS Soil Science Division discussed forest stand improvement practices on the homestead and the relationship of tree species in the woodlot to soil profiles.

Ellis noted that the target of the NRCS Crop Tree Release Program is to have about 20 to 40 trees per acre. He explained that a site index and class index determine the value of a stand. Many of the trees we saw in one stand on the Brochu Homestead were 65 to 70 feet tall at 60 years of age – “very good,” said Ellis. At another site, which was at the bottom of a hill and was wetter, the 60-year-old trees were about 25 feet tall, so this area would have a lower site index.

Butler had dug a soil pit in this lower area, highlighting a thick, dark surface comprised of highly decomposed organic matter over a loamy gray soil profile indicating that the site is saturated with water annually for an extended period of time. This contrasted with a pit he had dug on higher, drier ground where the soils had vibrant hues of yellow and red indicating more aerobic and suitable growing conditions.

Ellis told tour participants that in order for NRCS to allocate funds for conservation projects, individuals must have a Conservation Activity Plan (CAP) and a Forest Management Plan specific to the site. A Forest Management Plan may take two years to create and, for 100 acres, may cost about $1,500. Funding may be available from NRCS to cover 75 to 90 percent of this cost.

Applications for forestry cost-sharing programs are ranked with respect to soil quality, potential income generation and other site characteristics. Those with good soils and good tree species rank higher than poorer sites and species. A minimum of 10 acres of forest is required to apply for the NRCS program.

Sites ranking high enough for funding may participate in the NRCS Crop Tree Release Program or in the Pre-Commercial Thinning Program.

Butler discussed his work on ecological site evaluation. Just as NRCS has mapped soils throughout the United States and created soil survey maps (now online as the Web Soil Survey), it is currently developing an Ecological Site Survey. Scheduled to be completed nationwide by 2020, the survey will show which species favor a particular site. This will help with land-use decisions about what to expect in terms of tree growth, for instance, in 60 to 100 years.

|

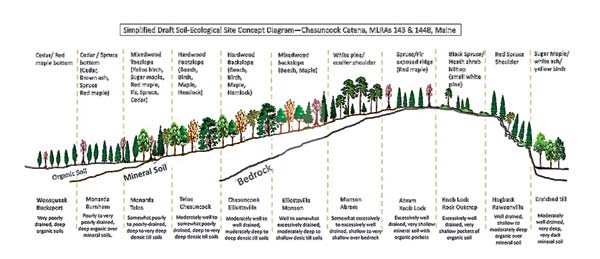

| A simplified draft diagram of preliminary ecological site concepts for 11 distinctive land types found on till soils in Maine. Courtesy of Nicholas Butler of USDA NRCS Soil Science Division |

According to a handout Butler distributed, “An ecological site is a land type classification based on recurring patterns in soils, climate, topography, hydrology, and geology. Each ecological site is distinctive from other land types in its ability to produce distinctive kinds and amounts of vegetation, and in its ability to respond to management and disturbances. Ecological site classifications are based on the assumptions that certain plant species grow better than others on certain soils and landscape positions, and that land with similar soils, climate, and landscape position can be expected to produce similar plant communities over time.

“Ecological site classes provide a baseline for the expected composition, productivity, and ecological function of a piece of land. For forests in Maine, that means explicitly stating which combinations of soils and topography are best suited to grow white pine, for example, compared to sites that are moderately or poorly suited to grow white pine (though they may grow other species very well) … ecological sites represent an effort to document what is known about soil-vegetation patterns in an organized manner.”

Butler presented a diagram of a simplified Chesuncook catena (a sequence of soil profiles down a slope) showing tree species associated with those soil series.

Landowners who would like to partner with NRCS in developing ecological site concepts in Maine by sharing data, land access, time and expertise to improve the ecological knowledge base for sustainable forest management may contact Butler in the Dover-Foxcroft soil survey office at [email protected].

Katy Green of MOFGA and Leslie Nelson, district conservationist for Piscataquis County NRCS, answered questions about NRCS practices and programs available to Maine residents, including the high tunnel cost-share program and Green’s work in helping write organic transition plans. Green said that Conservation Activity Plans can be written for transitioning to organic agricultural production, and that NRCS cost-share can help growers who want to work with her on these plans.

The Brochu Homestead tour concluded with a brief discussion of invasive species and a visit to a high tunnel. Funding is available from NRCS for controlling invasives and for constructing high tunnels.

In 2016 Katy Green was MOFGA’s organic transitions coordinator. Kacey Weber is the educational coordinator for the Piscataquis County Soil and Water Conservation District. Jean English edits The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.