|

| Trees need at least 20 percent of their total height to have living foliage to thrive and grow well. English photo |

|

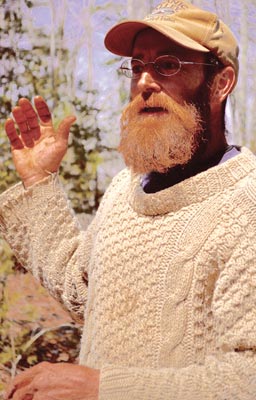

| Maine district forester Morten Moesswilde discussed different uses for a forest, depending in part on soil characteristics and existing species. English photo. |

By Katy Green and Jean English

Maine’s woodlots can provide income, materials for the farm, spiritual inspiration and more, as speakers revealed at a workshop on forestry and soil conservation held in Washington, Maine, in April by the Knox-Lincoln Soil & Water Conservation District. The workshop was presented in cooperation with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), Maine Coast Heritage Trust, the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, MOFGA and the Small Woodland Owners Association of Maine. Morning talks were followed by a tour of Eli Berry’s woodland in Washington; this tour was funded by the USDA NRCS, under number 69-3A75-16-012.

Forestry Resources

Morten Moesswilde, one of 10 district foresters with the Maine Forest Service, serves Waldo, Knox, Lincoln and Kennebec counties. Most Maine farms, he said, are 40 to 60 percent wooded. Sometimes landowners want to convert those woods to fields, or vice versa; or they want to use woods to silvopasture livestock. Some want to harvest biomass, lumber, edibles (e.g., maple syrup) or wreath brush. Forests may provide firewood to heat the home or greenhouse or to boil down maple sap. Woodlands may also provide recreation, wildlife habitat, aesthetics, privacy, and buffers from pesticide drift for organic growers.

A forest management plan – a document usually written with assistance from a licensed forester and usually covering 10 years – can help with those uses, said Moesswilde. Among the basics that landowners should know are their property boundaries, the stand type (beech-birch-maple, etc.) and condition, the volume and value of wood in an area, and a “prescription” for optimizing benefits from the forest. They should also know about wildlife habitats and water bodies.

The Web Soil Survey app (https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/App/HomePage.htm) can indicate, generally, the types of soils likely present and their potential uses, while a visit from state soil scientist David Rocque (see below) can provide more specific information.

Silviculture – culturing the forest – can include planting and pruning, said Moesswilde, but more often involves cutting some trees to favor others. He advised selecting species suited to the site and likely to survive.

Forest structure includes the ages, size classes and arrangement of crowns. Management can enhance available sunlight for desired trees.

Regarding timber harvesting, know who’s responsible for what, have the proper training (including safety training), know how to access the woods, know the market for trees before they’re felled, decide which harvest machinery to use (from pruning shears to large equipment) and how to lay out the trails and log yard, and know how slash – leaves and branches – will be handled. If anyone else is working on your property, have a written agreement clearly outlining the job, and follow up with the agreement, Moesswilde emphasized.

Know the Maine forestry rules, he continued (https://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/publications/index.html), and Best Management Practices (https://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/publications/handbooks_guides/bmp_manual.html).

|

| State soil scientist David Rocque dug several soil pits on Berry’s land to show color and drainage differences. English photo |

Moesswilde can meet with landowners to provide feedback about their woodlands, and help identify plant health issues. He also teaches classes on a variety of subjects. Moesswilde can help landowners learn whether a forest management plan might be useful for them. Both Maine Forest Service and NRCS have financial assistance programs for management plans. When harvesting, Moesswilde said, it’s often important to have a private forester help plan and oversee the job if landowners do not have the background to do it themselves, to obtain the results they want. Moesswilde helps landowners find private foresters to help with management plans and/or with timber harvesting.

Know Your Soils

David Rocque covered basic concepts relating to Maine soils and the importance of knowing about soils on a site – ideally before buying the land.

Rocque noted the usefulness and limitations of the Web Soil Survey. Soils were infrequently visited, so much of the mapping was based on aerial photos of land forms and what soil scientists believed soil types would be – sometimes mistakenly. Also, the smallest area mapped is about 3 acres.

Berry’s land, for example, is mapped almost entirely as Peru soil, which centers on being a moderately well drained sandy loam glacial till with a hardpan and a seasonal groundwater table at a depth of 16 to 40 inches, but the range of characteristics includes somewhat poorly drained soils with a seasonal groundwater table at a depth of 7 to 16 inches. “Eli might tell you that his land is most definitely on the wetter end of the scale,” said Rocque. Soil map units, he added, also have inclusions of other soils that are too small in size to show on the soil map, at the scale of mapping. These inclusions can be wetter or dryer than the named soil series.

Two kinds of groundwater tables can be found in most soils, continued Rocque. “In fairly flat areas, water can sit, and soil can become anaerobic and toxic to plants. On slopes, groundwater can move and may not become anaerobic or toxic but still present management issues. These and other conditions determine which plants will grow well.”

When Rocque visits a site, he can identify, for example, sites suitable for pasture, for excavating gravel, sites that would benefit from fill or that are unsuitable for certain crops. He can help determine how to manage a forest for best return. The potential for the soil, said Rocque, is more important than results of a soil test. The latter can be remedied; the former probably cannot.

In Berry’s forest he pointed out hummocky areas characteristic of wet soils, where red maple, silver birch and other moisture-tolerant species grow on mounds surrounded by pits. He also showed flatter, better drained areas with healthy growth of white pines. Participants viewed several soil pits Rocque had dug, seeing a uniformly dark brown color where level soil had been tilled in the past and then reverted to forest; grey or mottled soils from pits where excess water led to anaerobic conditions (intermittently, in the case of mottled soils) and to reduction and leaching of iron; lighter colored soils from better drained, flatter areas and from mounds; and olive brown soils with streaks of organic matter in them where oxygenated groundwater moves and carries organic matter with it.

Improperly clearing and stumping can lead to a water quality violation, a fine and the requirement to remedy the landscape if soil erodes into bodies of water. Rocque has collected every rule and regulation regarding agriculture – clearing land, putting in a farm pond, etc. – into a document for the public.

Oxygenated groundwater sites – those with enough slope that water moves through them – may support such valuable trees as sugar maple, white birch and northern white cedar – but these soils, which don’t look wet but do carry water, are subject to rutting and compaction if mishandled. If dammed by logging roads, for example, they can turn into wetlands – which the DEP may then require be protected.

“Understand the hydrology of the site, not just the soils,” said Rocque, adding, “Don’t try to manage the wrong species on a particular site. Manage the land for what is adapted there.”

|

| Eli Berry practices low-impact forestry on the most accessible acreage of his land. English photo |

|

| The woods road, with firewood logs in the foreground and a nursery planting of 3-year-old basswood along the shoulder. Photo by Eli Berry |

A “rock sandwich” road can be constructed on a site with a lot of oxygenated groundwater, said Rocque. Along the contour, cut a little on the uphill side, use that material as fill on the downhill side, install a filter pad on the base of the road, then a layer of stone, then another filter pad. Water moves through the stone. “You don’t have to dig big ditches and have water running down the ditch and through a culvert,” said Rocque. Instead, the rock sandwich spreads the water over a larger area and keeps it in the ground where it belongs.

Generational Values

Eli Berry, logger, woodland owner and MOFGA board member, and Stephanie Gilbert, farmland specialist with the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, discussed Berry’s farm in Washington. This was followed by a tour of Berry’s forest, managed using low-impact practices and incorporating innovative ways to increase production in the woods.

Both of Berry’s grandparents’ families moved to Maine with the 1950s back-to-the-landers. One grandfather bought a farm in Bowdoinham; the other in Washington. Berry’s mother, nursery stock grower Sharon Turner, grew up on the Washington farm, and Berry fished and hunted with his grandfather there, which tied him to the landscape and the ecology.

“I was really lucky,” said Berry. “I had land that was intimately known to my family, that I was able to become acquainted with. I learned very early on that it’s a relationship, it’s not a utility. My relationship with my woodlot was informed by my relationship with adults when I was little,” including his grandparents and a neighbor-logger who came with his oxen.

After graduating from Bowdoin College in 1993, Berry worked out West for a few years, found that he liked physical work and working with resources and with people who want a long-term relationship with the land. “I traveled enough to know that we have something special in Maine. For one thing, this landscape that’s incredibly diverse; [and] we have water!”

He returned to the long, narrow, 74-acre site that includes a level area near the road but drops off to steep forest land that straddles the headwater drainages of the Damariscotta and Medomak rivers.

He has reclaimed fields and has harvested and sold firewood and lumber. He enrolled the farm in the Maine Tree Growth Tax Program, which saved the land economically and forced Berry to make a plan rather than use the land reactively.

Now 46, he is reassessing his tools and methods. To date he has harvested with a mix of human (his own and neighbors’), animal and mechanical power. “The big change for me going ahead,” said Berry, “will be adjusting to harvest at a bigger scale, further into my lot, and by a contractor. I have to make decisions as I get older about how to do this and keep it fun.

“The thing about forestry,” he continues, “is that you have to look at the long term every year, because you might get a heavy, wet snow like we got two Thanksgivings ago that essentially flattened 6 acres.”

Berry said he sees in “tree time,” which is between geologic and human time, or three or four human generations. “I remember pruning trees with my grandfather in the ’70s, harvesting and milling [lumber for] an old barn in the ‘90s and seeing the stump that the tree came from.” He also deals with tree-time challenges, including his grandfather’s decision to cut in 1978 to pay bills. Skidder ruts from that operation left behind “parallel vernal pools.”

The Washington land is an important wildlife corridor in an area populated by gravel pits, said Berry, and his field edges are also important refuges for pollinators and wildlife. Along his fields and woods road, “I’m trying to replace that edge margin and make it one where I can get 50 quarts of blackberries, or [make it a] tree nursery where the soil is good and it’s close to the road.”

Berry noted that the highest part of his land consists of marine shale soils, so the house basement can hold water while a brook down below is dry. “The water doesn’t really want to leave,” he said. He used an NRCS cost-sharing program to build a 900-foot rock sandwich road. NRCS paid $5.82 per foot – half the cost. He has also used NRCS cost-sharing to build a fence, thin trees, improve the timber stand, create wildlife brush piles and put up hoop houses.

|

| A solar dryer for wood products. English photo |

|

| Berry built a small, efficient house rather than remodel the old farmhouse. English photo |

|

| Some of Berry’s perfect piles of firewood. Photo by Eli Berry |

|

| Firewood ready for boiling down maple sap. English photo |

The woods road solved the perennial issue of getting firewood out of the forest when the upper land was wet. Now, instead of trying to manage all of his forest, much of which is on steep land, he is using the road to maximize production in the 5 or 6 most accessible acres.

The 12-foot-wide road left a 40-foot gap in the woods, so paralleling that road is a 900-foot-long, 12-foot wide, stump-free, prepped seedbed for shade-tolerant nursery stock. “It’s not a ditch or an edge or a rough spot,” said Berry. “It’s a resource, a tree nursery!” He now digs young hemlocks from his woods, transplants them there and later sells them as landscape plants – rather than dealing with them as undergrowth simply to be controlled. Some of his mother’s nursery stock can also be grown alongside the woods road.

Gilbert noted that Berry’s business plan includes a vision and steps to achieve that vision. She quoted him as saying, “The revolution of the food economy is incomplete without thinking about fuel and building materials.” His holistic view of the forest reflects his idea that a woodlot needs a shepherd and that no management is a poor management decision, added Gilbert.

She also cited Berry’s orderly manner of work. For example, “No resource is cut without knowing how he’s going to use it.”

“A lot of what I do is incremental,” said Berry, and it does not always deliver a fat check. In 2016 he did his first saw log harvest. Before Berry cut, Ron Fickett, owner of Premium Log Yards Inc. of Coopers Mills, which buys high-end hardwood, “spent an hour and a half walking around, saying, ‘that one, cut it at 8 feet; that one, cut it at 16 …'” Loggers are aware, said Berry, that bigger, older trees are now to be found in more populous parts of the state and on smaller parcels of land rather than up north or in areas accessible to large equipment. So for the first time, Berry had someone pick up his logs and give him a check for $900.

Your income increases when you save time by working efficiently, Berry continued. For instance, he drops trees where he wants the brush to remain and deals with the brush first. He may use it to surround and protect a seedling tree that he wants to save, or to make wildlife brush habitat. Then he cuts off badly curved parts of the trunk – parts “truly unworthy of the necessary effort” – and throws these “knuckles” into the woods. Curved, forked or ungainly pieces of firewood end up in piles for outdoor boilers and camp wood. He splits the remaining straight wood with his maul.

“I believe that your habits are what make your habitat,” said Berry. He learned from his grandfather to leave something better than you found it – to think beyond your own immediate desires. “That’s where tree time comes in,” he said.

Engaging with trees in a relationship “helps me make sense of other things that can only be solved incrementally, whether building community or re-acclimating with neighbors.” The quick fix is not characteristic of the natural world, he said. Looking toward the hard work needed to address various issues, “we’re going to have to do it together,” Berry concluded, and “the woods are a great place for team work to happen.”

Resources

Eli Berry, Human Powered Forestry Tools, 207-242-5927, [email protected]

David Fuller, agriculture and non-timber forest products Extension professional, University of Maine Cooperative Extension Franklin County Office, 138 Pleasant Street, Suite #1, Farmington, ME 04938-5828; 207-778-4650; [email protected]

Stephanie Gilbert, farm viability and farmland protection specialist, Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, State House #28, Augusta, ME 04333; 207-287-7520; [email protected]

Morten Moesswilde, Maine Forest Service district forester, Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, 536 Waldoboro Road, Jefferson, ME 04348; 207-441-2895; [email protected]

David Rocque, state soil scientist, Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, State House #93, Augusta, ME 04333; 207-287-2666; [email protected]

Andy Shultz, landowner outreach forester, Maine Forest Service, Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, 22 State House Station, Augusta, ME 04330; 207-287-8430; [email protected]

|

| A boundary white pine with Eli and one of his nephews, Anibal Berry-Gaviria. Photo by Lisandro Berry-Gaviria |

“Forest Trees of Maine”

https://maine.gov/dacf/mfs/publications/handbooks_guides/forest_trees/index.html

Knox-Lincoln Soil & Water Conservation District

www.knox-lincoln.org (Includes the NRCS Web Soil Survey Tutorial at

https://www.knox-lincoln.org/usda-web-soil-survey-tutorial)

Maine Association of Conservation Districts

https://maineconservationdistricts.com

Maine Tree Farm Program

https://www.treefarmsystem.org/maine

MOFGA’s Low-Impact Forestry Program

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/site/me/home/

New England Forestry Foundation

https://www.newenglandforestry.org/

Small Woodland Owners Association of Maine (SWOAM)

https://www.swoam.org/

(“Know Your Soils: Woodland Tour Explores Growing Maine’s Most Perennial Crop,” by Jeanne Siviski, covers the “Beyond the Field Edge” workshop. See https://www.swoam.org/LandownerResources/tabid/94/ID/161/Know-Your-Soils-Woodland-Tour-Explores-Growing-Maines-Most-Perennial-Crop.aspx)

Soil and Water Conservation Districts (SWCD)

https://www1.maine.gov/dacf/about/commissioners/soil_water/index.shtml

Katy Green is MOFGA’s organic transitions coordinator.* Jean English is editor of The MOF&G.

* In 2017, Green moved from MOFGA’s agricultural services department to MOFGA Certification Services LLC, where she is now a certification inspector.