By Candace Gilpatric

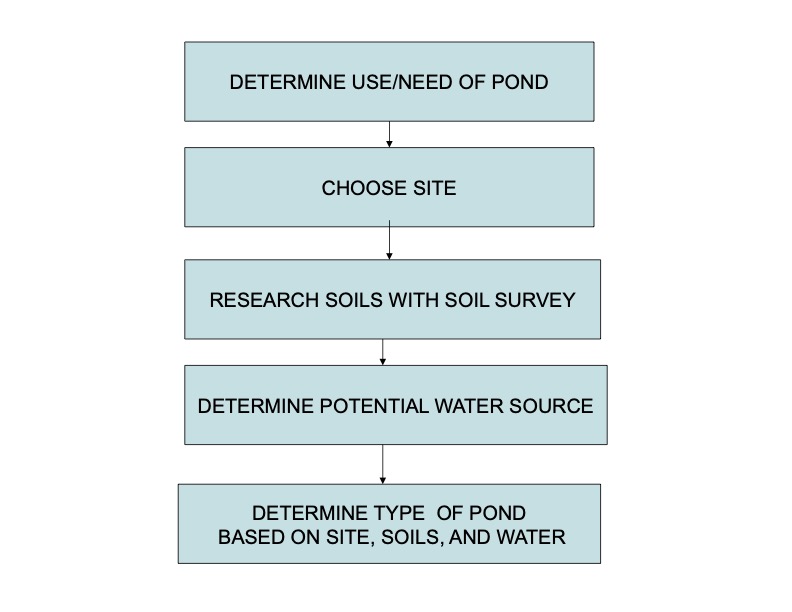

Ponds are desired for many reasons. Some people want a pond for aesthetic purposes, others want it for the peaceful joys of watching wildlife or recreating, and then there are some folks who want a pond for availability of water. Ponds can be a water source for fire protection, livestock watering, or irrigation. There are several factors to consider when trying to site and establish a good pond for these various uses.

Regulations and permitting vary based on location. If you are considering building a pond, it is best if you consult Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) or Maine Land Use Planning Commission (LUPC), or the equivalent in your state, and your local code enforcement officer to determine what regulations need to be followed.

There are two major factors that affect pond siting: the soil and the water source. A good place to start is by checking out the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Web Soil Survey. Find your location on the map and determine the soils. Each described soil will have tables listing where the seasonal high-water table falls, whether it is a permeable or dense soil, and if it is a good pond soil to hold water or not. These soil descriptions are accurate to about a 3-acre area. They only reflect the soils to a depth of 40 inches. Use this information to rule out the obvious.

After you have narrowed your options down to a few locations, it is time to do a test pit with an excavator. Be sure to dig the hole to the desired pond depth. If you are building this pond for trout, you will want a depth of at least 10 feet to ensure they have cold deep water during the summer months. It is also important to dig the hole during the dry season. A lot of times in Maine we have wet soils at the surface in April, but the water table drops in mid-summer. If you build a pond in those areas, you could have a dry puddle come August. Is there bedrock (ledge)? Bedrock is risky business. Water can come in along voids in bedrock, but it also can exit in fractures. How much of a risk taker are you? For me, I walk away from bedrock. Also assess the soil that you will be removing from the pond site. Do you need to use it to build a dam? Is it good-packing, impermeable material or is it full of rocks?

That leads me to my next set of questions. What kind of pond are you looking to build? Is your site relatively flat? Will you just be digging out a big hole and making a small 4-foot-high (or less) berm? If so, this is referred to as a dugout or excavated pond. This type of pond is usually located in a low area with ground water that travels into the pond through the soil. Let’s tie this back to your test pit: If you are going with an excavated pond, you want to have a soil that is, ideally, gray in color. This means that it stays wet throughout the year.

If you have a sloping hillside with an intermittent runoff of water, maybe spring flows, and you want to excavate out some but also install a dam across the gully, you have an embankment or dam pond. These tend to be more expensive to build and potentially more regulated. These also have a higher hazard risk associated with them. Therefore, I won’t go into much detail on embankment ponds, but I will share that it is important to key the dam into the existing landscape; build side slopes at a maximum steepness of 2:1; construct an outlet spillway that sets at least 1 foot below the top of dam; and to be sure to use a good-packing, minimal-seeping soil for dam construction.

I often get asked if a pond liner is an option if the natural soils are not conducive for water holding. The answer is yes but at a price. If you line a pond you need to make sure that no water is trying to get in from the soils. Liners can either be 12 inches of clay soils placed and compacted over the entire inside surface of the pond or synthetic liners placed inside an excavated hole. With synthetic liners, if you have water flowing under your liner it can make your liner float up. To prevent this problem, install subsurface drains around the base of the pond excavation and an outlet away from site. A lined pond can only store water delivered to it from surface flows. In most situations it is cheaper to build a pond in a suitable soil and pump the water a distance to fields than to perimeter drain and line a poor location. If there is a clay source nearby, that could be an exception.

We have discussed the soils, now let’s discuss the water source. The pond will fill eventually, and if you are going for wildlife, recreation, or aesthetics, you will be all set. But if you are using this pond for irrigation or livestock use, you need it to recharge frequently. In thinking about irrigation, a safe rule of thumb is that you need 1 inch of water per week over the crop’s growing season. Commonly accepted convention is that a full season of 14 weeks will require supplemental water for 7 weeks or 50% of the crops needs. The math gets a little weird here but bear with me. 1 inch x 7 weeks = 7 inches or 0.6 feet. Let’s use 1 acre of crop = 43,560 square feet. Therefore, the water that you need to store to have an adequate irrigation reserve is: 43,560 square feet x 0.6 feet, which equals 26,136 cubic feet or 195,500 gallons. This would be an 80-foot-long by 80-foot-wide by 8-foot-deep pond. You can downsize water needs if you are irrigating with drip tape, which concentrates water just to where your crop is. Your area to be irrigated would drop from the full acre to just the root area of crop. You won’t be applying irrigation water to travel paths. This is not accounting for any rain events that may help recharge the pond, but it also isn’t subtracting water lost to evaporation. If your pond is recharged by ground water and you feel confident that the water flow is reliable no matter how bad the drought event is, you can downsize your pond to account for 2 to 3 weeks of irrigation, depending how fast the pond recharges.

Maine gets 40 to 50 inches of rain a year, depending on location, and around 18 inches of evaporation over the summer months. Even if your pond has no inflowing water, it will still need a drain-off spot to get rid of the excess water that falls on its surface. To allow excess water to leave the pond, the easiest construction is a grass waterway that is 10 feet wide, at a minimum, and sits 18 inches lower than the top of the dam. It is a level control section that allows the water to leave in a slow, non-erosive flow. It is best to put the spillway on natural ground and not over fill material. This reduces risk of settlement, washout, and damage to the fill. For ponds with greater than 5 acres of ground draining into it, you should consider a rock spillway because flows may run too frequently to allow good grass establishment.

Many times, people opt for a pipe outlet instead of an open channel. If you do install a pipe outlet, I want to emphasize that horizontal pipes (installed like driveway culverts) are a high risk in freezing climates. When water freezes it expands; when your pond freezes, the ice surface lifts. When it does so, it hits the bottom edge of the pipe and lifts it, too. This creates a void under the pipe in the berm, and you now have a failing berm.

The quality of your water source is another important consideration. Is your water coming from sediment-laden flows such as roadside runoff or open, steep crop fields? Is your water coming from areas that are high in nutrient runoff? Is your water coming from heavily paved developed areas? All of these can affect algae growth, increased pond vegetation, and loss of storage. Poor water quality can plug filters and emitters in irrigation systems and deliver containments to produce.

From aesthetics to fire protection to irrigation water, a pond can be a valuable asset on your property. However, a pond is also a significant investment of time and money, and a professional should be consulted before starting a pond-building project. For more information, check out the NRCS publication “Ponds — Planning, Design, and Construction.”

Candace Gilpatric, PE is an agricultural engineer for the United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service. She has spent her 33-year career working in Maine assisting cooperators with conservation efforts including irrigation, nutrient management, forestry, and aquatic organism passage.

This article was originally published in the summer 2025 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.