By C.J. Walke, Orchard Program Manager

Sometimes I feel like a broken record, skipping back to the same themes and concepts, but always out of concern for organic growers and backyard orchardists who are just as susceptible, if not more so, to the common challenges of growing organic tree fruit in the Northeast as we are at MOFGA’s Maine Heritage Orchard. As I write this, on a cold, rainy day in April, we are in a reboot of plans and ideas for the 2025 growing season, looking over last year’s notes and activities, and thinking of improved fruit cultivation strategies for the Maine Heritage Orchard. Currently there are two strategies at the top of my mind for the beginning of the season that we will continue throughout the year: building soil health and battling fire blight.

Building Soil Health

Soil health is essential for organic growers, in terms of supporting diversity for the biological soil-dwelling buggers, balancing the levels and ratios of the chemical components, and working with the characteristics of the physical structure beneath our feet. The Maine Heritage Orchard originated a decade ago in a former gravel pit, requiring extensive earthwork to establish terraces and tree rows, and to date our fertility strategies have focused primarily on the tree-planting holes and a 2-to-3-foot radius around tree trunks.

The oldest trees, all grafted onto seedling Antonovka roots, are just coming into their bearing years, filling out the rows with scaffold branches reaching 8 to 10 feet out from their trunks. Last fall, we collected a series of soil samples throughout the orchard to learn fertility levels and what needs to be addressed this season. Our assumption was that levels close to the trunks would be decent, considering the focus of applications and observations of healthy “weed” growth in that region, so we took soil samples from the areas between the trees, roughly from the drip line of one tree to the drip line of the next.

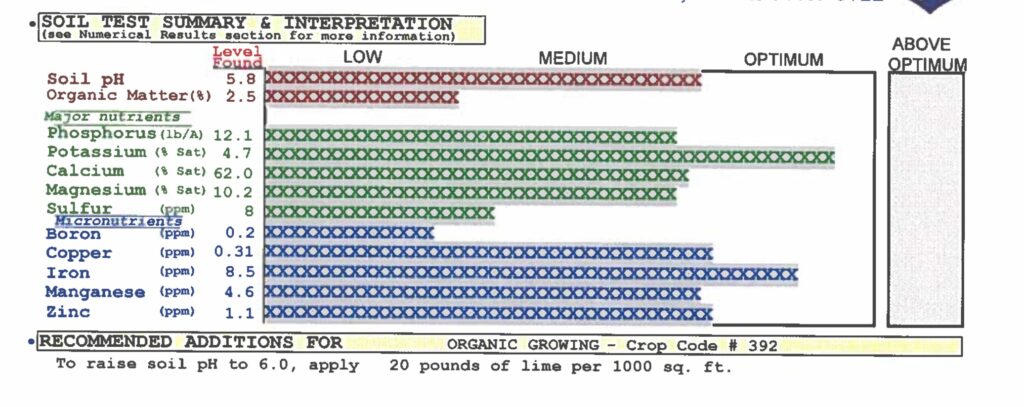

This is the region the trees will be growing into over the coming years and where we have focused less on building fertility. Soil pH ranges between 5.5 and 5.8 throughout the orchard in this inter-tree zone, calling for 20 to 50 pounds of lime per 1,000 square feet to raise the pH to 6.0. Some areas have sufficient magnesium levels, so we’ll use a calcitic lime to raise the pH and add calcium. Others need both calcium and magnesium, so we’ll use a dolomitic lime to raise the pH. We will add these amendments this spring, when the ground dries out and we can safely get equipment around the orchard.

The other soil gauge of interest is organic matter, which ranges from 1% to 3.4% in the Maine Heritage Orchard. We would like to see it around 5%, but considering the site started as a gravel pit and the original topsoil was removed, organic matter is on the rise. We tend to add organic matter in the form of two 5-gallon buckets of compost and two wheel barrows of wood chips per tree, per year. Material expense and availability are limiting factors here, but we are also shifting our mowing strategy to let the understory grow so we have more of a mulch left behind after mowing. Key mowing times are: early June to make dropped fruit easier to see and collect; early August to make summer apple harvest a little easier; and late fall for post-harvest orchard sanitation. There are always a few lush areas that need a touch up in between these primary times.

Battling Fire Blight

Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) tends to be the primary concern for the majority of the growing season. Most pests and pathogens will do some damage or decrease fruit quality, but fruit production is not the primary goal in our preservation orchard. Fire blight is the one pathogen that can infect a tree badly enough that we need to cut it down. This has happened a few times over the years and we’ve had replacement trees in MOFGA’s nursery or at collaborating farms to replant the cultivar, but it is not fun to start back at square one with a newly planted tree.

Fire blight is an aggressive bacterial disease of apple and pear, as well as many other plants in the Rosaceae (rose) family. The bacteria overwinter on established cankers on the trees. When temperatures reach 70 degrees Fahrenheit, cell division rapidly increases, with 80 degrees F being optimal for bacteria reproduction. With Maine’s current climate change trends, these temperatures and conditions are now very common during bloom in mid-May, which is the primary infection period for fire blight. Ten-plus years ago, fire blight was uncommon in backyard orchards and not present here in Unity, but now it’s a perennial challenge for most.

Our preparations begin in mid to late April, during the dormant or delayed dormant period, before buds open and new green tissue is roughly a quarter inch long. We use a liquid copper fungicide (Cueva) at one gallon per 100 gallons of water and we also mix in one gallon of horticultural oil (JMS Stylet) to double our efforts in one spray: Copper will kill bacteria overwintering on the trees and the oil will smother any overwintering pests or eggs. Dormant oil application is a classic organic pest management approach in orchards.

At the start of bloom, we use a newer product called Blossom Protect combined with its partner material called Buffer Protect. These products contain microbes that competitively colonize the open flowers, essentially taking up available space and nutrients, and blocking the fire blight bacteria from taking hold. Manufacturer recommendations are to apply these materials four times during bloom (10%, 40%, 70%, and 90% bloom), but realistically we are lucky to get two full applications of coverage during bloom considering weather, timing, and the orchard terrain. It is worth noting that Blossom Protect is harmless to humans, bees, and beneficial insects. We wear appropriate personal protective equipment for all materials sprayed in the orchard and spray primarily starting at sunrise with occasional evening applications if needed.

After bloom, we focus on another spray application of Cueva with a preventative biofungicide/bactericide called Double Nickel. We mix 2 quarts Cueva and 2 quarts Double Nickel in 100 gallons of water. From this point on, our focus is on scouting for shoot strikes for the rest of the summer, which usually does not end until terminal buds are set and shoot growth has ceased for the year by early September. Shoot strikes are the classic “shepherd’s crook” curling over and turning brown to black.

We prune these strikes out and remove them from the orchard to burn when possible or bag and dispose of them in the dumpster. Recent research suggests that pruning tools do not need to be sanitized between cuts, but we sanitize with isopropyl alcohol often. Strikes should be pruned out 12 inches below the start of the strike, which is completely nuanced and not always the most straightforward measurement to make. We tend to prune out more than less, to be on the safe side. In a worst-case scenario, we end up pruning out so much of an infected tree that we end up cutting it down while pruning in the dormant season. That’s the most painful cut, and it makes all the other work seem in vain, but sometimes that is the reality of life in the orchard.

Please note: Any reference to commercial products or trade or brand names is for information only and no endorsement or approval is intended. Pesticide registration status, approval for use in organic production, and other aspects of labeling may change after the date of this writing. It is always best practice to check on a pesticide’s registration status with your state’s board of pesticide control, and for certified organic commercial producers to update their certification specialist if they are planning to use a material that is not already listed on their organic system plan. The use of any pesticide material, even those approved for use in organic production, carries risk — be sure to read the label and follow all instructions. The label is the law. Pesticides labeled for home garden use are often not allowed for use in commercial production unless stated as such on the label.

This article was originally published in the summer 2025 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.