MOFGA Pesticides Quiz and Primer

How much do you know about pesticides and your health?

2024 Edition | By Sharon S. Tisher, J.D.

Dear reader, I hope you find this new edition of the Pesticides Quiz and Primer fun and enlightening, and a pathway to our collective better health. Since the last, 2015, edition, I have become a grandmother, which made completing this update personally more compelling. Coincident with the development of this edition, I am delighted to report that 15 years of Jean English’s MOF&G “Organic Matter” column are now available for your exploration, in a searchable PDF, covering a wide variety of science, policy, and health developments relevant to organic farming and gardening. Just click here to see it. “Organic Matter” was always my first resource in writing and updating the quiz. When MOFGA’s website was redesigned in 2021, the links to this column no longer worked. We have now substituted links to the Organic Matter Archive for cites to Jean’s column in the quiz answers.

False. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring raised public consciousness and understanding of the risks of pesticides and (a decade later) led to the cancellation of the registration of DDT and several other persistent and highly toxic pesticides (although they continued to be manufactured for use abroad). However, according to EPA estimates, 1.25 billion pounds of pesticide active ingredients were sold in 1995 in the United States, more than double the 540 million pounds sold in 1964. Adjusted for inflation, U.S. pesticide expenditures grew about 3 percent annually from the 1970s to the 1990s. The percentage of crop acres treated with herbicides rose from about 50 percent in the 1960s to more than 96 percent in the 1990s. (Benbrook, C.M., Pest Management at the Crossroads, Consumers Union, 1996, at 81-84.)

The EPA reports in 2011 that pesticide use in the United States decreased 8 percent from 1.2 billion pounds active ingredient in 2000 to 1.1 billion pounds in 2007 (https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-10/documents/market_estimates2007.pdf), and held steady at 1.1 billion pounds in 2011 and 2012. These EPA reports are only “occasional” and there is no more recent report available as of April 2023 (https://www.epa.gov/pesticides/pesticides-industry-sales-and-usage-2008-2012-market-estimates) The decrease from 2000 to 2007 was mainly in the agricultural sector and is probably largely due to wider use of genetically engineered crops that incorporate pesticides and that are not counted in these sales reports.

Charles Benbrook notes, however: “While Bt corn and cotton have reduced insecticide applications by … 123 million pounds [between 1996 and 2011] … , resistance is emerging in key target insects and substantial volumes of Bt Cry endotoxins are produced per hectare planted, generally dwarfing the volumes of insecticides displaced.”

Benbrook also concludes, “Overall, since the introduction of GE [genetically engineered] crops, the six major GE technologies have increased pesticide use by an estimated 183 million kgs (404 million pounds), or about 7%. The spread of GR weeds [weeds resistant to the herbicide glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup herbicide] is bound to trigger further increases, e.g., the volume of 2,4-D sprayed on corn could increase 2.2 kgs/ha by 2019 (1.9 pounds/acre) if the USDA approves unrestricted planting of 2,4-D HR [herbicide-resistant] corn.” (Benbrook, C.M., “Impacts of genetically engineered crops on pesticide use in the U.S. — the first sixteen years,” Environmental Sciences Europe 2012, 24:24; https://enveurope.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/2190-4715-24-24)

The brightest news in the 2011 EPA report of pesticide usage is that, thanks to stricter regulation under the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 (FQPA), use of organophosphate pesticides, potent neurotoxins, decreased more than 70 percent in the United States from 2000 to 2012.

In its collection of the 100 most important people of the 20th century, Time magazine wrote: “Before there was an environmental movement, there was one brave woman and her very brave book.” The hundredth anniversary of Carson’s birth was celebrated on May 27, 2007, with the recognition that the struggle for truth and caution that she pioneered is ongoing. In The New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert wrote, “As much as any book can, Silent Spring changed the world by describing it,” but, “Six years into the Bush Administration, it’s basically the ant wars all over again. At key agencies, a disregard for inconvenient evidence seems to be a prerequisite.” (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/05/28/human-nature) Meanwhile, Senator Tom Coburn from Oklahoma blocked a resolution to laud Carson in Congress, blaming her for using “junk science” to turn the public against DDT. (https://www.reuters.com/article/environment-carson-dc/senator-blocks-honor-for-environmental-pioneer-idUKN2547056820070525)

The Trump Administration’s 2017 refusal to follow the EPA staff recommendation that the toxic pesticide chlorpyrifos be banned in agriculture was an early salvo in the escalation of those “ant wars.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/04/12/why-did-scott-pruitt-refuse-to-ban-a-chemical-that-the-epa-itself-said-is-dangerous/ [see answer to Q. 8]

False. Even the EPA concedes that its pesticide registration process is no guarantee of safety. EPA regulations specifically prohibit manufacturers of pesticides from making claims such as “safe,” “harmless” or “non-toxic to humans and pets” with or without accompanying phrases such as “when used as directed.” (40 CFR sec. 156.10(a)(5)(ix))

False. The legal standard for registration set down by the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) is, unlike most other environmental statutes, a “risk-benefit” standard. EPA must register pesticides if they do not pose “unreasonable risk to man or the environment, taking into account the economic, social and environmental costs and benefits of the use of any pesticide.” (7 USC secs. 136(bb) and 136a(c)(5)(C), emphasis added) This means that if a pesticide presents substantial benefits to farmers in terms of increased yields or decreased labor costs, those benefits are weighed against health and environmental risks. Even if there are substantial health risks, the EPA may decide the economic benefits outweigh the risks. The federal Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 (FQPA) did away with the economic benefit analysis for new tolerances for dietary risk but left it unchanged for human occupational exposures and environmental risks.

False. Toxicity tests are performed neither by the EPA nor by independent laboratories contracting with the EPA. Pesticide manufacturers provide the data on which the EPA bases its judgments. An inherent conflict of interest exists between EPA’s need for unbiased data and the manufacturers’ need for data that show their products are not hazardous. For examples of biased and fraudulent testing, see Center for Biodiversity, “Failure to Regulate: Pesticide Data Fraud Comes Home to Roost,” April 9, 2015, https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/media-archive/a2015/pesticides_truthout_4-9-15.pdf

Manufacturers contend that fear of lawsuits keeps them honest, but this argument hardly holds water for long-term, chronic consequences of pesticide exposure, such as cancer or decreased sperm counts, which show up years after exposure.

A March 2013 study by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that EPA oversight of manufacturer toxicity testing was lacking in many cases: “the government has allowed the majority of pesticides onto the market without a public and transparent process and in some cases, without a full set of toxicity tests, using a loophole called a conditional registration. In fact, as many as 65 percent of more than 16,000 pesticides were first approved for the market using this loophole.” The report included case studies of two pesticides –clothianidin and nanosilver – to show how conditional registration has been misused. https://www.nrdc.org/media/2013/130327, https://www.nrdc.org/experts/jennifer-sass/nrdc-reveals-failed-safeguards-pesticides-bad-actor-pesticides-including

False. In 2010, the President’s Cancer Panel, a congressionally mandated panel of experts working under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute, released a landmark report, “Reducing Environmental Cancer Risk, What We Can Do Now.” A letter by the authors to President Obama concluded that the U.S. government has “grossly underestimated” the “true burden of environmentally induced cancers.” (http://abcnews.go.com/Health/Wellness/cancers-environment-grossly-underestimated-presidential-panel/story?id=10568354) The report noted, “Approximately 40 chemicals classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as known, probable, or possible human carcinogens, are used in EPA-registered pesticides now on the market. Some of these chemicals are used in several different pesticides … Thus, the total number of registered pesticide products containing known or suspected carcinogens is far greater than 40, but few have been severely restricted in the United States … Pesticides … approved for use by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) contain nearly 900 active ingredients, many of which are toxic. Many of the solvents, fillers, and other chemicals listed as inert ingredients on pesticide labels also are toxic, but are not required to be tested for their potential to cause chronic diseases such as cancer.” (President’s Cancer Panel, Reducing Environmental Cancer Risk, 2010, p. 45, http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/pcp08-09rpt/PCP_Report_08-09_508.pdf )

Among the formal recommendations of the report are that families reduce their exposure to pesticides by “choosing, to the extent possible, food grown without pesticides or chemical fertilizers and washing conventionally grown produce to remove residues. Similarly, exposure to antibiotics, growth hormones, and toxic run-off from livestock feed lots can be minimized by eating free-range meat raised without these medications if it is available.” (President’s Cancer Panel Report, p. 112)

A 2012 review of the epidemiological literature linking pesticides to cancers in occupational studies including agriculture world-wide found that “Chemicals in every major functional class of pesticides including insecticides, herbicide, fungicides, and fumigants have been observed to have significant associations with an array of cancer sites,” including prostrate, lung, colorectal, pancreatic and non-Hodgkin lymphoma cancers. The authors conclude: “Since use of pesticides world-wide results in exposure to millions of workers occupationally and to hundreds of millions of people through nonoccupational routes of exposure, identifying potential carcinogens among these chemicals should be an important public health priority.” (“Occupational pesticides exposure and cancer risk. A Review,” by Michael Alavanja and Matthew Bonner, J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2012; 15(4): 238–263, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6276799/)

Beyond Pesticides reports that “[w]hile agriculture has traditionally been tied to pesticide-related illnesses, 19 of 30 commonly used lawn pesticides and 28 of 40 commonly used school pesticides are linked to cancer.” (http://www.beyondpesticides.org/health/cancer.php) The Beyond Pesticides website links to specific research reports, broken down by type of cancer.

One of the most debated and litigated pesticide issues in recent years is whether the herbicide Roundup, with the active ingredient glyphosate, is a carcinogen. The EPA reports that glyphosate is the most commonly used herbicide in the United States, in terms of area treated; that about 280 million pounds of glyphosate are applied to an average of 298 million acres of crop land annually; and that “glyphosate is important for noxious and invasive weed control in aquatic systems, pastures/rangelands, public lands, forestry, and rights-of-way applications. Glyphosate is the leading herbicide used to control invasive species in the United States.” https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-04/documents/glyphosate-response-comments-usage-benefits-final.pdf

In March, 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an arm of the World Health Organization, stunned pesticides proponents by declaring the active ingredient in Roundup, glyphosate along with the widely used insecticides Malathion and Diazinon, “probable carcinogens.” (http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/pdf/MonographVolume112.pdf) The classification is not binding on governments.

The EPA Office of Pesticide Programs released a ‘Glyphosate Issue Paper: Evaluation of Carcinogenic Potential” in 2016, concluding that the herbicide is not a probable carcinogen. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/glyphosate_issue_paper_evaluation_of_carcincogenic_potential.pdf That conclusion has been affirmed in subsequent agency reviews. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/glyphosate

In 2017, Monsanto was ordered to disclose internal emails and email exchanges with federal regulators in a lawsuit by people who claimed they contracted non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma from exposure to Roundup. According to the New York Times, “The records suggested that Monsanto had ghostwritten research that was later attributed to academics and indicated that a senior official at the Environmental Protection Agency had worked to quash a review of Roundup’s main ingredient, glyphosate which was to have been conducted by the United States Department of Health and Human Services. The documents also revealed that there was some disagreement within the E.P.A. over its own safety assessment.” (Danny Hakim, “Monsanto Weed Killer Roundup Faces New Doubts on Safety in Unsealed Documents,” New York Times, March 14, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/14/business/monsanto-roundup-safety-lawsuit.html?_r=0)

Ironically, in the same month as these disclosures, the Trump Administration USDA decided to scrap plans in the works for over a year to test 315 samples of corn syrup, which is predominantly produced from “Roundup Ready” corn, for residues of glyphosate.( http://glyphosate.news/2017-04-06-usda-scrubs-plan-to-test-foods-for-dangerous-levels-of-monsantos-glyphosate.html)

In July 2017, the State of California listed glyphosate as a known carcinogen under California Prop 65, which requires consumer warnings on all packages of products containing listed chemicals. Monsanto sued to overturn the listing, won in the trial court, but the California appellate court upheld the listing in April, 2018. (https://oehha.ca.gov/proposition-65/crnr/glyphosate-listed-effective-july-7-2017-known-state-california-cause-cancer; https://www.commondreams.org/news/2018/04/20/win-science-and-democracy-court-rules-california-can-list-glyphosate-probable) In April, 2019 the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) released the long-awaited Draft Toxicological Profile for Glyphosate, which supported and strengthened the IARC’s 2015 determination that glyphosate is a probable carcinogen. https://www.nrdc.org/bio/jennifer-sass/atsdr-report-confirms-glyphosate-cancer-risks But in August 2019 the Trump Administration EPA flew to the defense of Roundup and similar products, announcing that it will not approve California mandated product labels linking glyphosate with cancer. https://newfoodeconomy.org/epa-california-cancer-glyphosate-monsanto-prop-65/) And in 2020 a federal court sided with Bayer in California litigation and ruled that glyphosate warning labels could not be required under Prop 65. https://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/press-releases/6053/judge-overrides-california-state-warning-label-of-glyphosate-pesticide-as-probable-carcinogen-under-proposition-65#

Writing for the journal Environmental Sciences Europe in 2019, Charles Benbrook took a hard look at why the IARC and the EPA reached such diametrically opposite conclusions as to the carcinogenicity of glyphosate. His conclusions: “(1) in the core tables compiled by EPA and IARC, the EPA relied mostly on registrant [manufacturer]-commissioned, unpublished regulatory studies, 99% of which were negative, while IARC relied mostly on peer-reviewed studies of which 70% were positive (83 of 118); (2) EPA’s evaluation was largely based on data from studies on technical [pure] glyphosate, whereas IARC’s review placed heavy weight on the results of formulated … assays [studies of glyphosate-based herbicides including additives that can enhance the toxicity of the active ingredient]; (3) EPA’s evaluation was focused on typical, general population dietary exposures assuming legal, food-crop uses, and did not take into account, nor address generally higher occupational exposures and risks [such as farmworkers and other commercial applicators, and do-it-yourself homeowners].” Charles Benbrook, “How did the US EPA and IARC reach diametrically opposed conclusions on the genotoxicity of glyphosate-based herbicides?” Environmental Sciences Europe, January 14, 2019, https://enveurope.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s12302-018-0184-7

Despite the EPA’s position, American juries have come down decidedly on the side of plaintiffs in suits against Monsanto claiming their non-Hodgkin lymphomas were caused by exposure to glyphosate, awarding billion dollar punitive damage verdicts that have been reduced by trial judges to millions. (See reports in the Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, Jean English, “Organic Matter,” December 2018-February 2019; June-August 2019; September-November 2019)

As Claire Brown put it in The New Food Economy, “Simply put, it may become too expensive for Bayer [owner of Monsanto] to keep Roundup on the shelves for much longer.”(https://newfoodeconomy.org/epa-california-cancer-glyphosate-monsanto-prop-65/) In 2020, Bayer reached a settlement agreement to pay more than $10 billion to settle tens of thousands of claims while continuing to sell the product without adding warning labels about its safety. (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/business/roundup-settlement-lawsuits.html) In 2021, Bayer announced that it would stop selling Roundup with glyphosate for residential lawns and gardens use in 2023, a move it claimed “is exclusively geared at managing litigation risk and not because of any safety concerns.” “Roundup” will still be marketed, but with an alternative, as of yet unidentified, active ingredient. (https://cen.acs.org/environment/pesticides/Bayer-end-glyphosate-sales-US/99/web/2021/07)

In 2021 the Maine legislature approved legislation sponsored by Maine Senate President Troy Jackson that would have banned the aerial spraying of glyphosate in Maine forests. Governor Janet Mills vetoed the measure. Maine Public quoted Senator Jackson: “‘The science across the country, across the world, says that this stuff kills people, kills wildlife,’ Jackson says. ‘And all that it is, is a giveaway to the large landowners so they can maximize their profits off the lives of the people in Maine and the wildlife in Maine.’…A logger by trade, Jackson has seen the effects of clearcutting and herbicide use in the woods of northern Maine. For years, he and other residents have been raising concerns about possible water contamination and related health effects from the chemical. But they got strong pushback from large landowners and the forest products industry who say the use of aerial herbicides in Maine is limited and that it’s the most efficient way to control vegetation that competes with more valuable timber species like spruce and fir.” Susan Sharon, “Mills Vetoes Bill That Would Have Banned Aerial Herbicide Spraying In Woods,” Maine Public, June 25, 2021, https://www.mainepublic.org/environment-and-outdoors/2021-06-25/mills-vetoes-bill-that-would-have-banned-aerial-herbicide-spraying-in-woods

The Guardian reports that a study published in January, 2023 by scientists with the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control “measured glyphosate levels in the urine of farmers and other study participants and determined that high levels of the pesticide were associated with signs of a reaction in the body called oxidative stress, a condition that causes damage to DNA. Oxidative stress is considered by health experts as a key characteristic of carcinogens.” (Carey Gillam, “People exposed to weedkiller have cancer biomarkers in urine – study,” The Guardian, January 20, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/jan/20/glyphosate-weedkiller-cancer-biomarkers-urine-study)

Evidence is mounting that glyphosate residues are pervasive in our food system. In 2017, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency announced that it found traces of glyphosate in nearly one third of 3,188 domestic and imported food products it tested. (http://www.cbc.ca/news/health/cfia-report-glyphosate-1.4070275) A study of residues of glyphosate and its metabolite in the urine of 100 adults found substantial increases in prevalence and amount of exposure over two decades: from 12 detects in samples from 1993-96, to 70 detects in samples from 2014-16. The mean concentration of glyphosate in detects more than doubled during this period. (“Analysis: Glyphosate exposure trends demand a public health driven response,” by Dr. Richard Jackson and Charles Benbrook, Environmental Health News, Oct 30, 2017; http://www.ehn.org/analysis-glyphosate-exposure-trends-demand-a-public-health-driven-response-2502467074.html)

Carey Gillam reported in The Guardian in 2018 that internal FDA documents reveal that the FDA has had trouble finding any food that does not contain traces of glyphosate. Residues have been found in crackers, granola, cornmeal, honey and oatmeal products – sometimes exceeding the legal limit of 5.0 parts per million. (“Weedkiller found in granola and crackers, internal FDA emails show,” by Carey Gillam, The Guardian, April 30, 2018; https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/apr/30/fda-weedkiller-glyphosate-in-food-internal-emails)

Jean English reports in the Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, Winter 2018-2019, that “Independent tests commissioned by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) found glyphosate residues in all but two of 45 samples of products made with conventionally grown oats, such as oat cereals, oatmeal, granola and snack bars. Almost three-fourths of those samples had glyphosate levels higher than 160 parts per billion (ppb), which EWG scientists consider protective of children’s health with an adequate margin of safety, so a single serving of those products would exceed EWG’s health benchmark. About one-third of 16 samples made with organically grown oats contained glyphosate – at levels well below EWG’s health benchmark.” (Jean English, “Organic Matter,” The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, Winter 2018-2019; https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news-release/roundup-breakfast-weed-killer-landmark-cancer-verdict-found-kids-cereals)

EWG updates: https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/2018/10/new-round-ewg-testing-finds-glyphosate-kids-breakfast-foods-quaker-oats;

https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news-release/2018/10/roundup-breakfast-part-2-new-tests-weed-killer-found-all-kids; https://www.ewg.org/childrenshealth/monsanto-weedkiller-still-contaminates-foods-marketed-to-children; https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/glyphosate-contamination-food-goes-far-beyond-oat-products.)

And a 2018 study by government scientists in Canada found glyphosate in 197 or 200 samples of honey they examined. (“Weed killer residues found in 98 percent of Canadian honey samples,” by Carey Gillam, Environmental Health News, March 22, 2019; https://www.ehn.org/weed-killer-residues-found-in-98-percent-of-canadian-honey-samples-2632384800.html) See also, answer to Q. 9, Roundup inerts)

In January, 2024, the highly influential American Academy of Pediatrics, a “go-to source for practicing pediatricians and some parents,” released a guidance urging parents to avoid foods with ingredients from genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The guidance cautioned, as reported in Science, “about potential health harms, especially to infants and children of residues in food from the weed killer glyphosate, which is widely used on genetically engineered crops.” Meredith Wadman, “Pediatrics academy faces pushback on GMO advice,” Science, September 20, 2024, https://www.science.org/content/article/pediatrics-academy-accused-fearmongering-over-gmo-ingredients-kids-diets; Steve Abrams, Jaclyn Albin, and Philip Landrigan, “Use of Genetically Modified Organism (GMO)-Containing Food Products in Children,” Pediatrics, January, 2024, https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/153/1/e2023064774/196193/Use-of-Genetically-Modified-Organism-GMO

For the recent story of the EPA’s handling of another Monsanto herbicide, dicamba, associated with increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and liver cancer in farmers, see Tom Perkins, “EPA accused of failing to regulate use of toxic herbicides despite court order,” The Guardian, April 24, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/apr/24/epa-monsanto-toxic-herbicides-dicamba: “The EPA’s move is another example of the agency “treating the pesticide industry not as regulated companies, but as clients”, said Nathan Donley, environmental health science director with the Center For Biological Diversity.”

False. Developing fetuses, newborns and young children are among the most vulnerable to pesticides in our population, and the least protected. A 1993 study by the most preeminent scientific body in the United States, the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences, found that “infants and children differ both qualitatively and quantitatively from adults in their exposure to pesticide residues in foods. Children consume more calories of food per unit of body weight than do adults. But at the same time, infants and children consume far fewer types of foods … The current regulatory system does not, however, specifically consider infants and children … Current testing protocols do not, for the most part, adequately address the toxicity and metabolism of pesticides in neonates and adolescent animals or the effects of exposure during early developmental stages and their sequelae in later life.” (National Research Council, “Pesticides in the Diets of Infants and Children,” 1993, Pages 1 -13; http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=0309048753)

The Council recommended a 10-fold additional safety factor in setting pesticide tolerances for pesticide residues on foods to protect children. The 1996 federal Food Quality Protection Act mandated revision of tolerances to accomplish this. In 2006 the EPA announced that it had completed a 10-year review of U.S. pesticide safety, focusing on the special risks presented to children. However, environmental activists and some of the EPA’s own scientists question whether the EPA had enough information to set safe tolerance levels. (See answer to Q. 16.)

Concern continues to grow that widespread exposure to pesticide residues in food and home environments contributes significantly to growing rates of childhood cancers, asthma, obesity, autism, and other endocrine and neurodevelopmental disorders in the United States and abroad. (See generally, Andre Leu, “The Myths of Safe Pesticides” (2014), Pages 13-25, 40-47; Pesticide Action Network, “A Generation in Jeopardy: How pesticides undermine our children’s health and intelligence,” 2012; http://www.panna.org/publication/generation-in-jeopardy; and Environmental Working Group reports, answer to Q. 5)

In 2010 the President’s Cancer Panel (see answer to Q. 5) concluded: “There is a critical lack of knowledge and appreciation of environmental threats to children’s health and a severe shortage of researchers and clinicians trained in children’s environmental health.” (http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/pcp08-09rpt/PCP_Report_08-09_508.pdf, Page 98)

A 2016 study found significant decreases in I.Q. and verbal comprehension in seven year olds whose mothers had, during pregnancy, lived within approximately 1 km from agricultural fields in California where multiple neurotoxic pesticides were used. (“Prenatal Residential Proximity to Agricultural Pesticide Use and IQ in 7-Year-Old Children,” by Robert B. Gunier et al., Environmental Health Perspectives, 7/25/2016; https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/EHP504

Researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in a 2017 study of over 500,000 births between 1997 and 2011 in California’s San Joaquin Valley, found that premature births rose by about 8 percent and birth abnormalities by about 9 percent where pesticide use was the greatest. (“Agricultural pesticide use and adverse birth outcomes in the San Joaquin Valley of California,” by Ashley Larsen et al., Nature Communications, Aug. 29, 2017; https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-00349-2)

For a compelling photo essay on the impact of pesticides on children in farming communities in Argentina, where birth deformities increased four-fold after 10 years of intensive cultivation of genetically engineered Roundup Ready soybeans, see “Legal Toxins” by Alvaro Ybarra Zavala (https://vimeo.com/102238995, see also http://www.i-sis.org.uk/Devastating_Impacts_of_Glyphosate_Argentina.php)

A 2020 Environmental Working Group investigation published in Environmental Health found that for almost 90 percent of the most common non-organophosphate pesticides, the agency had neglected since 2011 to apply the Food Quality Protection Act–mandated children’s 10-fold health safety factor to the allowable limits. (“EWG Study: EPA Fails To Follow Landmark Law To Protect Children From Pesticides in Food,” February 12, 2020, https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news-release/ewg-study-epa-fails-follow-landmark-law-protect-children-pesticides-food; Olga Naidenko, “Application of the Food Quality Protection Act children’s health safety factor in the U.S. EPA pesticide risk assessments,” Environmental Health, February 10, 2020, https://ehjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12940-020-0571-6)

False. These products fundamentally contradict the principles and practices of organic cultivation as well as of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), which require least toxic means of pest management to be applied only after a pest problem has been identified, and not routinely. For this reason, and based on a recommendation of Maine Board of Pesticides Control staff, Governor John Baldacci took the important step of banning these fertilizer/pesticide mixtures, and other pesticides used for purely cosmetic purposes, for use on state-owned and managed office buildings and their grounds. (“An Order Promoting Safer Chemicals in Consumer Products and Services,” February 22, 2006, http://www.maine.gov/tools/whatsnew/index.php?topic=Gov_Executive_Orders&id=21193&v=Article)

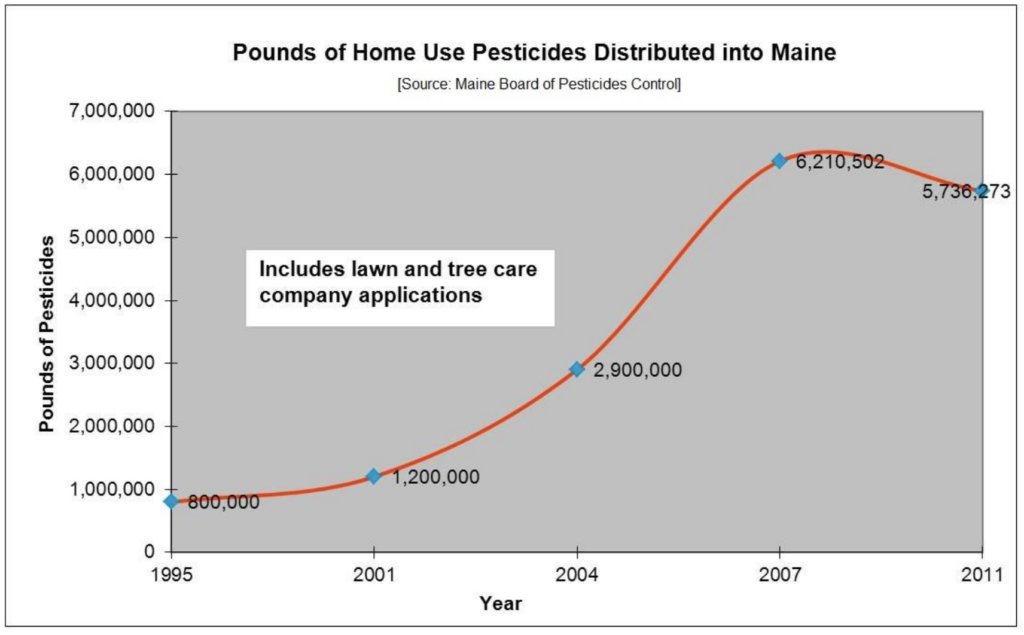

Unnecessary use of lawn and yard care synthetic chemicals is a skyrocketing problem in Maine. According to the Maine Board of Pesticides Control, use of yard care pesticides in Maine increased sevenfold from 1995 to 2007; more than 6.2 million pounds of yard care pesticides were brought into Maine in 2007. (https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-02/documents/pespwire-winter.pdf, p. 5)

For information and resources on how to have a beautiful yard with fewer or no synthetic chemicals, see the BPC’s YardScaping web pages: http://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/pesticides/yardscaping/index.htm

False. Neurotoxicity, as well as risks to the human immune, reproductive and endocrine systems, may be equally or even more significant.

Neurotoxicity

A 2006 analysis published in the distinguished medical journal The Lancet concluded that tiny amounts of common pollutants, including pesticides, may be causing a “silent pandemic” of neurological disorders impairing development of fetuses and infants. Among the potential consequences are lower IQ scores and conditions such as autism, attention deficit disorder and cerebral palsy. (Grandjean and Landrigan, “Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals,” The Lancet, November 8, 2006; http://www.env-health.org/IMG/pdf/06tl9094page.pdf)

A 2014 follow up study by the same authors analyzed strong epidemiological evidence of the neurotoxicity of six industrial chemicals, including the organophosphate pesticide chlorpyrifos (trade names Lorsban, Dursban), banned for most residential uses in the United States under the FQPA but still used in food production. The authors concluded, “To control the pandemic of developmental neurotoxicity, we propose a global prevention strategy. Untested chemicals should not be presumed to be safe to brain development, and chemicals in existing use and all new chemicals must therefore be tested for developmental neurotoxicity.” ( Grandjean and Landrigan, “Neurobehavioral effects of developmental toxicity,” The Lancet, February 14, 2014, http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laneur/article/PIIS1474-4422(13)70278-3/abstract)

A 2016 EPA Human Health Risk Assessment of chlorpyrifos found residues in many foods at levels up to 14,000 percent higher than “safe” limits. “EPA: Toxic Pesticide on Fruits, Veggies Puts Kids at Risk,” by Miriam Rotkin-Ellman and Veena Singla, Natural Resources Defense Council, Jan. 6, 2017; https://www.nrdc.org/experts/miriam-rotkin-ellman/epa-toxic-pesticide-fruitsveggies-puts-kids-risk; “Chlorpyrifos Revised Human Health Risk Assessment (2016),” U.S. EPA, https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454)

Chlorpyrifos is used on about 40,000 farms on about 50 different types of crops, ranging from almonds to apples. EPA scientists concluded that exposure to chlorpyrifos was potentially causing health consequences, particularly learning and memory declines among farmer workers and young children, and the agency in late 2016 proposed to ban all agricultural uses of chlorpyrifos. Under the Trump Administration, one of EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt’s first actions was to reject the proposed ban, commenting that “[b]y reversing the previous Administration’s steps to ban one of the most widely used pesticides in the world, we are returning to using sound science in decision-making – rather than predetermined results.” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/29/us/politics/epa-insecticide-chlorpyrifos.html, https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-administrator-pruitt-denies-petition-ban-widely-used-pesticide-0). Pruitt’s action came 20 days after a private meeting with the CEO of Dow Chemical, the primary chlorpyrifos manufacturer, and two months after Dow contributed $1,000,000 to the Trump inaugural balls. ( https://www.ewg.org/news-and-analysis/2018/03/thanks-scott-pruitt-30-million-pounds-brain-damaging-pesticide-will-be#.WxbExO4vzIU) The American Academy for Pediatrics and the Environmental Working Group sent a letter to Pruitt protesting the rejection of the ban, observing that “[t]he risk to infant and children’s health and development is unambiguous. The clear statutory language of the FQPA requires that EPA revoke tolerances in the face of uncertainty. EPA has no new evidence indicating that chlorpyrifos exposures are safe. As a result, EPA has no basis to allow continued use of chlorpyrifos, and its insistence in doing so puts all children at risk.” (https://www.ewg.org/testimony-official-correspondence/nation-s-pediatricians-ewg-urge-epa-ban-pesticide-harms-kids#.WxbGKu4vzIV)

In June 2021 Maine Governor Janet Mills signed legislation requiring the phase out of chlorpyrifos in agriculture by 2022, a bill sponsored by Representative Victoria Doudera of Camden and strongly supported by MOFGA. The Maine Medical Association lauded the legislation, saying “This bill would ensure that pregnant mothers, babies and young children will not be exposed to this harmful pesticide through chlorpyrifos application in Maine.” Christian Wade, “Maine Approves Ban on Pesticide Chemical,” The Center Square, June 11, 2021, https://www.thecentersquare.com/maine/mills-approves-ban-on-pesticide-chemical/article_36a51606-cab9-11eb-841b-936452383386.html; 7 MRSA sec. 606.

Not to be outdone, in August 2021, the Biden Administration announced that it was banning chlorpyrifos for use on food crops because it has been linked to neurological damage in children. As a result of a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision ordering the administration to halt the agricultural use of the chemical unless it could demonstrate its safety, the ban was expedited to take effect in six months. This is estimated to eliminate more than 90 percent of the use of chlorpyrifos in the US. The federal ban is limited, however– unlike the Maine legislation– to food crops. Coral Davenport, “E.P.A. to Block Pesticide Tied to Neurological Harm in Children,” New York Times, August 18, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/18/climate/pesticides-epa-chlorpyrifos.html

Enter from backstage in the continuing battle over chlorpyrifos: the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals in November 2023 vacated the EPA’s order banning use of the pesticide on food crops, concluding it was “arbitrary and capricious,” and directing the EPA to conduct further review to consider whether it could end some food uses of chlorpyrifos but allow others to continue. Erin Fitzgerald, “In Shocking Decision, 8th Circuit Sends Chlorpyrifos Food Use Ban Back to EPA,” Earthjustice press release, November 2, 2023, https://earthjustice.org/press/2023/in-shocking-decision-8th-circuit-sends-chlorpyrifos-food-use-ban-back-to-epa (For an analysis of the conservative “political-party bias” of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, compared with the lack of such bias in the Ninth Circuit, see Robert Steinbuch, “An Empirical Analysis of Conservative, Liberal, and Other ‘Biases’ in the United States Courts of Appeals for the Eighth & Ninth Circuits, 11 Seattle J. for Soc. Just. 217 (2012), https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1139&context=faculty_scholarship)

In May 2023, researchers from UCLA and Harvard Researchers reported a study that pinpointed 10 pesticides that significantly damage neurons involved in the onset of Parkinson’s disease. “The study utilized California’s extensive pesticide use database and innovative testing methods to identify pesticides directly toxic to dopaminergic neurons, which are crucial for voluntary movement. Combinations of pesticides used in cotton farming were more harmful than any single pesticide.” (Jason Millman, “Identifying Pesticide Culprits in Parkinson’s Disease,” Neuroscience News.com, May 18, 2023, https://neurosciencenews.com/parkinsons-pesticides-23276/; Kimberly Paul et al., “A pesticide and iPSC dopaminergic neuron screen identifies and classifies Parkinson-relevant pesticides,” Nature Communications, May 16, 2023, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-38215-z) See also, Carey Gillam, “Revealed: The secret push to bury a weedkiller’s link to Parkinson’s disease,” The Guardian, June 2, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/jun/02/paraquat-parkinsons-disease-research-syngenta-weedkiller, reporting Syngenta’s effort to “secretly influence scientific research regarding links between its top-selling weedkiller [paraquat] and Parkinson’s.”

For a fascinating examination of the challenges of connecting outbreaks of brain diseases in New Brunswick, Canada, to environmental causes, with forest applications of the herbicide glyphosate among the potential culprits, see Greg Donahue, “They All Got Mysterious Brain Diseases. They’re Fighting to Learn Why,” New York Times, August 14, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/14/magazine/canada-brain-disease-dementia.html

Hormone disruption

While Rachel Carson wrote of the hormone (“endocrine”) disrupting and reproductive effects of pesticides in Silent Spring in 1962, it took an astonishing 34 years, until the 1996 Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA), for Congress to mandate that the EPA consider these effects in regulating pesticides. It took another nine years before the EPA announced in June 2007 that it would begin screening 73 pesticides, including chlorpyrifos, malathion and atrazine, for their risk of endocrine disruption, once it finalized its standards for review. (72 FR 33486) While some regulatory actions by the EPA under the FQPA have considered endocrine effects, a 2011 report of the Inspector General found that the EPA’s Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program, 14 years after passage of the FQPA, had missed many deadlines and “has not determined whether any chemical is a potential endocrine disruptor.” (https://www.epa.gov/office-inspector-general/report-epas-endocrine-disruptor-screening-program-should-establish) A 2012 study published in Endocrine Reviews argued that the approach the EPA was taking to identify endocrine disrupting chemicals and assess their risk was fundamentally flawed, because it relied on the centuries old notion that the “dose makes the poison,” or that smaller doses create less risk: “For decades, studies of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) have challenged traditional concepts in toxicology … because EDCs can have effects at low doses that are not predicted by effects at higher doses … Thus, fundamental changes in chemical testing and safety determination are needed to protect human health.” (Laura Vandenburg and coauthors, “Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses”, Endocrine Reviews, Volume 33, Issue 3, 1 June 2012, p. 378–455, https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/33/3/378/2354852 ) The EPA has largely rejected this assessment, in a draft report praised by the American Chemistry Council.

It was not until June, 2015 that EPA published its first preliminary results for testing for “estrogen receptor bioactivity” on 1,800 chemicals. That report, 19 years after Congress mandated consideration of endocrine disruption effects, cautioned that “[t]hese data do not provide a scientific basis, by themselves, supporting a conclusion that chemicals or substances have potential for endocrine disruption.” (https://www.epa.gov/endocrine-disruption/endocrine-disruptor-screening-program-edsp-estrogen-receptor-bioactivity)

In March, 2023, 27 years after passage of the FQPA, the EPA released the results of its “Tier 1” testing of 52 chemicals for potential endocrine disruption, culled from the original 1,800 selection: “Of the 52 chemicals evaluated, there was no evidence for potential interaction with any of the endocrine pathways for 20 chemicals, and for 14 chemicals that showed potential interaction with one or more pathways, EPA already has enough information to conclude that they do not pose risks. Of the remaining 18 chemicals, all 18 showed potential interaction with the thyroid pathway, 17 of them with the androgen pathway, and 14 also potentially interacted with the estrogen pathway.” Those 18 chemicals are slated for further, “Tier 2” testing. The EPA release cautioned that “the screening results for these 52 chemicals are only determinations of their potential to disrupt endocrine function. A result indicating potential should not be construed as meaning that EPA has concluded that the chemical is an endocrine disruptor.” (https://www.epa.gov/endocrine-disruption/endocrine-disruptor-screening-program-edsp-tier-1-assessments)

A comprehensive report by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Health Organization, State of the Science of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals 2012, pointed out the alarmingly “high incidence and the increasing trends of many endocrine-related disorders in humans,” including “large proportions (up to 40%) of young men in some countries have low semen quality, which reduces their ability to father children;” “genital malformations, such as non-descending testes (cryptorchidisms) and penile malformations (hypospadias), in baby boys;” “the incidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm birth and low birth weight;” “increased global rates of endocrine-related cancers;” and “the prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes [which] has dramatically increased worldwide over the last 40 years.” Put simply, the report noted that “[h]uman and wildlife health depends on the ability to reproduce and develop normally. This is not possible without a healthy endocrine system.” The report identified industrial chemicals, including pesticides, as a probable cause of these disruptions of the endocrine system: “[c]lose to 800 chemicals are known or suspected to be capable of interfering with hormone receptors, hormone synthesis or hormone conversion. However, only a small fraction of these chemicals have been investigated in tests capable of identifying overt endocrine effects in intact organisms. The vast majority of chemicals in current commercial use have not been tested at all.” (http://www.who.int/ceh/publications/endocrine/en/).

For a summary of the evidence that pesticides play a significant role in impairing the endocrine system, see Andre Leu, “The Myths of Safe Pesticides,” 2014, Pages 34-47.

False. Inerts are almost always chemically functional and are added intentionally to enhance the performance of the “active” ingredient. They are generally solvents, emulsifiers, synergists or compounds that in some way make the active ingredient work better. Recent research demonstrates that the inerts not only enhance the intended effect of the active ingredient; they also may enhance its toxicity to humans and wildlife. Hence our regulatory system, which bases safety reviews primarily on testing active ingredients and which fails to even inform consumers of the identity of the inerts, is fundamentally flawed.

In 2006, the attorneys general of fifteen states, including Maine, petitioned the EPA to require that inert chemicals be disclosed in pesticides labeling. The petition stated that 360 chemicals used as inerts in pesticides had in fact been identified by the EPA or OSHA as hazardous under regulatory schemes other than the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. The petition argued that the public interest in knowing about these hazardous additives trumped any claim the manufacturers asserted about trade secrets: “the public’s interest in disclosure of a hazardous ingredient overrides any commercial interest in preserving confidentiality.” (https://ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/court-filings/Petition.As_Submitted._8_1_06.pdf) In 2009, in response to this and a similar petition by environmental organizations, the Obama Administration EPA requested public input on two alternative proposals regarding inert ingredient disclosure: one to disclose only ingredients identified as hazardous; the other to require disclosure of all inerts. The EPA noted that it “agrees with the petitioners that inert ingredient disclosure should be greatly increased.” The EPA proposal astutely noted that disclosure “may lead to less exposure to … hazardous inert ingredient[s] because consumers will likely choose products informed by the label.” In turn, “pesticide producers will likely respond by producing products with less hazardous inert ingredients.” (74 FR 68215 – Public Availability of Identities of Inert Ingredients in Pesticides, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/FR-2009-12-23/E9-30408) When the EPA failed to take further action on this rulemaking for the next three years, on March 5, 2014, the Center for Environmental Health, Beyond Pesticides, and Physicians for Social Responsibility, represented by Earthjustice, sued the EPA. (http://www.beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/?p=12888) In the last weeks of the Obama Administration, the EPA announced that it was removing 72 inert ingredients from its list of approved ingredients in pesticide products, noting that “Many of the 72 inert ingredients removed with this action are on the list of 371 identified by the [environmental ngo] petitioners as hazardous.” (https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-prohibits-72-inert-ingredients-use-pesticides_.html)

On January 9, 2017, the EPA announced that it would begin rulemaking to require that so-called “inert” ingredients be listed on the label with the “more neutral term ‘Other ingredients.’” In encouraging manufacturers to substitute “other” for “inert” on their labels before rulemaking becomes final, the EPA noted that “… EPA has long known and acknowledged that some inert ingredients are not benign to human health or the environment. The “inert” ingredients in some products may be more toxic or pose greater risks than the active ingredient.” ( PRN 97-6: Use of Term “Inert” in the Label Ingredients Statement, https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/prn-97-6-use-term-inert-label-ingredients-statement).

The Trump Administration did not proceed to prohibit the use of the term “inert,” or require public disclosure of those ingredients. Nor has the Biden Administration. In July, 2017, the Center for Food Safety (CFS) filed a rulemaking petition with the EPA asking it to fundamentally revise pesticide approval procedures, to require and assess safety data on the entire formulation, rather than just the “active” incredients. (https://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/press-releases/5012/center-for-food-safety-demands-trump-administration-close-pesticide-loopholes)

In a July 2022 EPA web page, “Basic Information about Pesticide Ingredients,” the EPA states that “the name ‘inert’ does not mean non-toxic. All inert ingredients must be approved by EPA before they can be included in a pesticide. We review safety information about each inert ingredient before approval. If the pesticide will be applied to food or animal feed, a food tolerance is required for each inert ingredient in the product, and we may limit the amount of each inert ingredient in the product.” The public, however, is not entitled to identification of those inert ingredients: “Under federal law, the identity of inert ingredients is confidential business information. The law does not require manufacturers to identify inert ingredients by name or percentage on product labels. In general, only the total percentage of all inert ingredients is required to be on the pesticide product label.” https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/basic-information-about-pesticide-ingredients

In October, 2022, the Center for Food Safety sued the EPA for failing to respond to its 2017 petition, and failure to adequately consider and regulate the toxicity of “inert” ingredients. Contrary to the language in the above EPA web page, the CFS contends that “most EPA regulations only require toxicological data from a pesticide’s active ingredients, rather than requiring data from active, inert, and adjuvant ingredients in the pesticide. The [CFS 2017] petition alleges that without considering the effects of all ingredients, the EPA cannot determine whether a pesticide formulation will have unreasonably adverse effects on the environment.” (Walker Livingston, “Center for Food Safety sues EPA over unanswered petition on inert ingredients in pesticides,” AgencyIQ, October 18, 2022, https://www.agencyiq.com/blog/center-for-food-safety-sues-epa-over-unanswered-petition-on-inert-ingredients-in-pesticides/)

Research on the controversial herbicide Roundup has focused on disturbing evidence concerning one of its inert ingredients. As reported by Beyond Pesticides, “About 100 million pounds of Roundup are applied to U.S. farms and lawns every year and until now, most health studies have focused on the safety of glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup, rather than the mixture of ‘inert’ ingredients found in the herbicidal product. In this new study, ‘Glyphosate Formulations Induce Apoptosis and Necrosis in Human Umbilical, Embryonic, and Placental Cells,’ researchers found that Roundup’s inert ingredients amplified the toxic effect on human cells – even at concentrations much more diluted than those used on farms and lawns, and which correspond to low levels of residues in food or feed. One specific inert ingredient, polyethoxylated tallowamine, or POEA, was more deadly to human embryonic, placental and umbilical cord cells than the herbicide itself – a finding the researchers call ‘astonishing.’ POEA is a surfactant, or detergent, derived from animal fat. It is added to Roundup and other herbicides to help them penetrate plants’ surfaces, making the weed killer more effective.” (http://www.beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/?p=1997; Nora Benachour and Gilles-Eric Séralini, “Glyphosate Formulations Induce Apoptosis and Necrosis in Human Umbilical, Embryonic, and Placental Cells,” Chem. Res. Toxicol.200922197-105, December 23, 2008, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/tx800218n.) POEA is not one of those inert ingredients removed by the Obama Administration from permitted use in pesticides in 2016.

Even more disturbing is the fact that after publication of this research, in May 2013, the EPA granted Monsanto’s petition to increase maximum residue limits of glyphosate on food and other crops. (78 FR 25396, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-05-01/pdf/2013-10316.pdf)

A 2018 study of inert and active ingredients in Roundup and other pesticides published in Toxicology Reports concluded that “the difference between ‘active ingredient’ and ‘inert compound’ is a regulatory assertion with no demonstrated toxicological basis.” (“Toxicity of formulants and heavy metals in glyphosate-based herbicides and other pesticides,” N. Defarge et al., Toxicology Reports, Vol. 5, 2018; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221475001730149X)

False. The Maine Board of Pesticides Control and similar agencies in other states regularly apply to the EPA, at the request of pesticide applicators, for “emergency approval” of unregistered pesticides to meet “special local needs,” or “FIFRA 24c Special Local Needs Registrations. To accommodate applicators because of administrative delays in formally registering products, these applications are often granted, repeatedly for the same product. These products have been registered for some agricultural and other uses, but not for the “special local needs” use, so no tolerance setting “safe” levels of residue has been set. https://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/pesticides/24C_registrations.shtml

False. It may reduce some residues, but definitely not all. The Environmental Working Group’s 2023 Shoppers Guide to Pesticides in Produce reports on pesticide contamination of fresh produce using USDA and FDA testing data. EWG reports: “The USDA peels or scrubs and washes produce samples before testing, whereas the FDA only removes dirt before testing its samples. Even after these steps, the tests still find traces of 251 different pesticides.” In this year’s report, nearly 75 percent of non-organic fresh produce sold in the U.S. contained residues of potentially harmful pesticides. Blueberries and green beans joined the Dirty Dozen list of the 12 fruits and vegetables sampled that have the highest traces of pesticides. Those most contaminated foods were: Strawberries; Spinach, Kale, Collard and Mustard greens; Peaches; Pears; Nectarines; Apples; Grapes; Bell and hot peppers; Cherries; Blueberries; Green beans. Consult the website for more on the pesticides detected, and the “Clean Fifteen.” (“Environmental Working Group’s 2023 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce,” https://www.ewg.org/foodnews/summary.php#summary)

A 2012 study in Europe also found that washing did little to remove pesticide residues; peeling was more effective, but most vitamins are found in the peels of fruits and vegetables. (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2112767/How-pesticides-persist-wash-fruit-veg.html)

Washing and peeling would have little effect, moreover, on systemic pesticides (pesticides that are absorbed by plants and distributed throughout all parts of the plants), such as neonicotinoids, introduced in 1998 and growing in use significantly. (http://www.motherearthnews.com/nature-and-environment/systemic-pesticides-zmaz10onzraw.aspx#axzz39ztnmMjA)

False. This was thought to be the case, as many pesticides illegal in the United States are still manufactured in the United States and elsewhere for use in other countries. The developing world has a far less comprehensive system of pesticide regulation than the United States. However, a 1999 study by Consumer Reports found that, surprisingly, domestic produce had more, or more toxic, pesticide residues than imported in two-thirds of the cases studied. Domestic peaches had a pesticide toxicity score 10 times higher than imported peaches. (Consumer Reports, March, 1999, p. 28)

A 2009 study published in the Journal of Food Chemical Toxicology reached similar findings: “Of the 15 pesticides for which quantifiable residues were detected from both domestic and imported fruit and vegetable samples, domestic exposures were significantly higher for 11 pesticides while imported exposures were higher for the remaining four. The five pesticides showing the highest exposures all demonstrated greater domestic exposures than imported exposures.” (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19059451)

The 2022 report of the Food and Drug Administration’s Pesticide Residue Monitoring Program, which tests for 750 different pesticides in domestic human food samples from 35 states and imported human food samples from 79 countries/economies, found that “no pesticide residues were found in 40.8% of the domestic samples and 48.4% of the import samples.” However, where residues were found, imported foods were somewhat more likely to violate U.S. standards: “96.8% of domestic and 88.4% of import human foods were compliant with federal standards, that is, the pesticide tolerances set by EPA.” (FDA Releases FY 2020 Pesticide Residue Monitoring Report, August 10, 2022, https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-releases-fy-2020-pesticide-residue-monitoring-report)

Not necessarily– unless you’re careful about the source of your seeds or plants. A study released in June 2014 by Friends of the Earth, “Gardeners Beware, 2014,” revealed that 51 percent (36 out of 71) of “bee-friendly” garden plant samples purchased at top garden retailers (Home Depot, Lowe’s and Walmart) in 18 U.S. and Canadian cities contained highly controversial neonicotinoid insecticides – a key contributor to recent bee declines: “Some of the flowers contained neonicotinoid levels high enough to kill bees outright assuming comparable concentrations are present in the flowers’ pollen and nectar.” (https://foe.org/resources/gardeners-beware-2014/) The same month, a meta-analysis of 800 studies by a Task Force on Systemic Pesticides convened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature found that neonicotinoid pesticides “are causing significant damage to a wide range of beneficial invertebrate species and are a key factor in the decline of bees.” (https://saiplatform.org/our-work/news/systemic-pesticides-pose-global-threat-to-biodiversity-and-ecosystem-services/)

In May 2014, a study released by the Harvard School of Public Health replicated a 2012 finding from the same research group linking low doses of the neonicotinoid imidacloprid with Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), in which bees abandon their hives and eventually die. The study also found that low doses of a second neonicotinoid, clothianidin, had the same negative effect. The study’s findings suggest that the pesticides, rather than mites or other bee pathogens, are a primary factor in triggering CCD. (http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/study-strengthens-link-between-neonicotinoids-and-collapse-of-honey-bee-colonies/)

Since these findings many major retailers with thousands of U.S. locations have made commitments to keep neonicotinoid-treated plants out of their stores. Consult the Friends of Earth’s webpage on Retailer Commitments on Pesticides and Pollinator Health for up-to-date information on these commitments. https://foe.org/nursery-retailer-commitments/

The EPA’s regulatory actions to protect pollinators by restricting the use of neonicotinoids as of July, 2022 are summarized at https://www.epa.gov/pollinator-protection/epa-actions-protect-pollinators

On June 11, 2021, Maine Governor Janet Mills signed the nation’s strongest restriction on bee-killing neonicotinoids into law, which was strongly supported by MOFGA. Sponsored by Rep. Nicole Grohoski of Ellsworth the legislative resolve prohibits the use of the most harmful neonic pesticides in residential landscapes. Environment Maine, Maine governor signs bill to save the bees, June 11, 2021, https://environmentamerica.org/maine/media-center/maine-governor-signs-bill-to-save-the-bees/; see also, Beyond Pesticides, https://beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/2021/06/maine-bans-consumer-use-of-neonicotinoid-insecticides-with-some-exceptions/; Maine Board of Pesticides Control, https://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/pesticides/applicators/neonicotinoids.shtml See MOFGA Deputy Director Heather Spalding’s summary of this and other accomplishments in the 2021 legislative session, and the need for yet further progress: “Time for an Intervention with Pesticide Regulators: 60 Years After “Silent Spring,” We Need Systemic Change,” https://www.mofga.org\/news/time-for-an-intervention-with-pesticide-regulators/

True. In September, 2016, the FDA issued a final rule that prohibits consumer antiseptic wash products (including liquid, foam, gel hand soaps, bar soaps, and body washes) containing the majority of the antibacterial active ingredients, which are legally classified as pesticides. The FDA concluded that “there isn’t enough science to show that over-the-counter (OTC) antibacterial soaps are better at preventing illness than washing with plain soap and water. To date, the benefits of using antibacterial hand soap haven’t been proven. In addition, the wide use of these products over a long time has raised the question of potential negative effects on your health.” (https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm378393.htm)

Of particular concern is the pesticide triclosan and its chemical cousin triclocarban, which since the 1990s have been added to numerous consumer products, including soaps, body washes, toothpaste, deodorant, facial cleansers and other cosmetics. The Natural Resources Defense Council reports that surveys have found residues of triclosan in more than 75 percent of Americans tested, and that the chemical has been associated with lower levels of thyroid hormone and testosterone, which could result in altered behavior, learning disabilities or infertility. https://www.nrdc.org/media/2013/131122)

After the 2016 ban on washing products, triclosan remained allowed in many other consumer products, including Colgate Total toothpaste and hand sanitizers, as well as surgical scrubs. (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/07/well/live/why-your-toothpaste-has-triclosan.html?_r=0) The FDA banned it in hospital soaps in 2017 and hand-sanitizer in 2019 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is now removed from virtually all products.

The National Institutes of Health has awarded a team of researchers at the University of Maine $420,000 to research the potentially negative effects of triclosan on the body’s mast cells – cells that respond to cancer, fight bacterial infections and play a role in central nervous system disorders such as autism. These researchers have also found that triclosan disrupts mitochondria, the energy powerhouses of the cell in many species, including human skin cells.(http://vitalsigns.bangordailynews.com/2014/08/01/public-health/is-your-antibacterial-soap-safe-umaine-researchers-study-common-ingredient/, email from Professor Julie Gosse, 3/27/17; https://umaine.edu/news/blog/2018/05/25/biochemist-physicist-team-see-antibacterial-tcs-deform-mitochondria/; https://umaine.edu/news/blog/2020/12/30/gosse-caps-decade-of-research-into-troublesome-triclosan/)

True. PFAS — “per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances” — are any of a family of more than 9,000 synthetic chemicals widely deployed since,the 1950s in a multitude of industrial and consumer products. They are extremely stable and hard to break down in the environment, and hence known as “forever chemicals.” And highly toxic. Beyond Pesticides reports that “PFAS is present in the bloodstreams of 97% of the U.S. population. Exposure to these compounds has been linked to a variety of human health anomalies, including cancers, kidney dysfunction, neurodevelopmental compromise in children, immunosuppression, pre-eclampsia, increased risk of cardiometabolic diseases (via exposure during pregnancy), and respiratory system damage.” https://beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/2022/04/maine-moves-to-ban-pesticides-and-fertilizers-contaminated-with-pfas/ PFAS have been identified as contaminants in soil and water in Maine and across the nation. Using municipal and industrial sludge as fertilizer is a major source of this contamination, but use of synthetic pesticides is likely a significant source as well.

On October 21, 2022, Pamela J. Bryer, Ph.D., the Pesticides Toxicologist for the Maine Board of Pesticides Control reported to the Board that the federal pesticide product registry database (NSPIRS) identified 69 active ingredients contained in a total of 1,493 registered pesticide products that are likely to contain PFAS. Additionally, pesticide products that do not contain PFAS by intentional addition are likely contaminated by PFAS in the containers in which they are stored and sold. Approximately 20 to 30% of the plastic containers used for pesticides are fluorinated. An EPA study concluded that oil-based and water-based fluids are both likely to contain PFAS following storage in fluorinated plastic containers.

A report of a study released in May, 2023 by the Center for Biological Diversity and Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility revealed that California’s most-used insecticide, Intrepid 2F, along with two other pesticides, Malathion 5EC and Oberon 2SC, were contaminated with potentially dangerous levels of PFAS. Center for Biological Diversity, “High Levels of Dangerous ‘Forever Chemicals’ Found in California’s Most-Used Insecticide 40% of Tested Agricultural Pesticide Products Contain PFAS,” May 2, 2023, https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/high-levels-of-dangerous-forever-chemicals-found-in-californias-most-used-insecticide-2023-05-02/, https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/pesticides_reduction/pdfs/J113812-1-UDS-Level-2-Report-Final-Report.pdf; Matthew Rozsa, “How did nonstick “forever chemicals” get into our food? Blame pesticides,” Salon, May 16, 2023, https://www.salon.com/2023/05/16/how-did-nonstick-forever-chemicals-get-into-our-food-pesticides/

Help is on the way, but it may be a long and winding road. In 2021, the Maine legislature passed a landmark law banning carpets or rugs, or fabric treatments containing PFAS effective January 1, 2023, and providing that effective January 1, 2030 “a person may not sell, offer for sale or distribute for sale in this State any product that contains intentionally added PFAS, unless the department has determined by rule that the use of PFAS in the product is a currently unavoidable use.” 38 MRSA sec. 1614. The legislature also passed a resolve, sponsored by Representative Bill Pluecker, “Directing the Board of Pesticides Control To Gather Information Relating to Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the State.” The resolve required the BPC to require companies registering pesticides annually with the Board to distributors to “provide affidavits stating whether the registered pesticide has ever been stored, distributed or packaged in a fluorinated highdensity polyethylene container and to require manufacturers to provide an affidavit stating whether a perfluoroalkyl or polyfluoroalkyl substance is in the formulation of the registered pesticide.” http://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/getPDF.asp?paper=HP0185&item=3&snum=130 Representative Pluecker followed this up with legislation in 2022 that requires the BPC to adopt rules related to pesticide containers, and provides that pesticides that have been contaminated by PFAS, by its containers or otherwise, may not be registered for use in Maine. It also requires separate registration of all “spray adjuvants” – such as wetting agents or spreading agents – that have been added to pesticide formulations, and that may contain PFAS. https://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/pesticides/documents2/bd_mtgs/May22/8a-LD_2019.pdf For a BPC slide show on its various legislative mandates regarding PFAS and pesticides, see https://legislature.maine.gov/doc/8215

Mofga.org News quotes Bill Pluecker on these legislative successes, responding to a comment in a public hearing: “Describing PFAS as ‘something that’s not so good’ is perhaps inaccurate, said the bill’s sponsor Rep. Bill Pluecker of Warren, who also worked hard to pass the ban on sludge spreading. ‘PFAS causes cancer, it causes low birth weight, it causes high cholesterol — all things that Maine is struggling with. It has poisoned our farmers, it has poisoned our deer and our fish, it has poisoned our land, water and food. This seems a little worse than ‘not so good.’” And also quotes Sen. Stacy Brenner, a champion of the successful legislation to ban spreading sludge on Maine farmland, an organic farmer and a member of MOFGA’s board of directors: “We say that dilution is the solution to pollution, but when we talk about chemicals that are dangerous in the parts per billion level, chemicals that bioaccumulate in our bodies and chemicals that react on the body’s endocrine system, dilution is not the solution. Containment is. Elimination is.” “Mofga Celebrates Landmark PFAS Policies, Mofga.org News, April 26, 2022, https://www.mofga.org\/news/maine-pfas-legislation/

Maine is a national leader in tackling PFAS in pesticides. This, from the June 6, 2023 Maine Public: “Under a law passed last year, pesticides that contain ‘intentionally added’ PFAS cannot be sold in Maine starting in 2030. In the meantime, Maine’s Board of Pesticides Control has begun compiling a list of chemicals that the state has flagged as belonging to the PFAS family. The Environmental Working Group, which is a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that is heavily focused on chemical safety, used that growing list and pesticide registrations in Maine to identify more than 1,400 pesticides that contain active ingredients that meet the state’s definition of PFAS. The group released a list of those 55 active ingredients on Tuesday as part of its campaign to highlight potential PFAS exposure to agricultural workers, gardeners and consumers. Lillian Zhou, a law fellow with the group, said she believes Maine is the first state to begin collecting this information on PFAS in pesticides. ‘But we hope that other states will follow too and take the protective approach that Maine has to ban intentionally added PFAS from all pesticides,’ Zhou said. ‘And we also hope that this will really give pesticide manufactures a push to start phasing out PFAS from their products.’” (https://www.mainepublic.org/environment-and-outdoors/2023-06-06/national-group-uses-maine-data-to-highlight-pfas-in-pesticides)

An excellent resource on regulating and avoiding the risks of PFAS is Marina Schauffler’s newsletter, ContamiNation. See, for example, the August 4, 2024, issue: “Reducing PFAS Exposure from Food,” https://marinaschauffler.substack.com/

For the 2024 update on MOFGA’s campaign against PFAS contamination, including actions you can take and a webinar on PFAS on farms and food, see https://www.mofga.org\/advocacy/pfas/

True, although even some organic food has tested positive for trace residues of synthetic pesticides, as a result of the background exposure to these chemicals in our soils, air, waters and transportation vehicles and storage facilities. Organic foods are much less likely to have residues, and when found, residue levels are well below those found and legally permitted in conventional food. (See Baker et al., “Pesticide residues in conventional, IPM-grown and organic foods: Insights from three U.S. data sets,” Food Additives and Contaminants, Volume 19, No. 5, May 2002; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12028642)

A University of Washington study analyzed pesticide breakdown products (metabolites) in pre-school aged children, comparing children eating at least 75 percent organic food with children eating at least 75 percent conventional food. The study found median concentrations of organophosphate metabolites six times lower in the children with the organic diets, and mean concentrations nine times lower, suggesting that some children eating conventional produce had much higher concentrations of metabolites. (See Curl et al., “Organophosphorus pesticide exposure and suburban pre-school children with organic and conventional diets,” Environmental Health Perspectives, October 13, 2002; https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.files/fileID/13642) A 2006 study in Environmental Health Perspectives similarly concluded that, “Organic Diets Significantly Lower Children’s Dietary Exposure to Organophosphorus Pesticides.” (Chensheng Lu et al., Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 114, n. 2, February 2006, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3436519?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents)

There have been similar findings for adult populations. A 2015 study of 4,500 adults from six U.S. cities examined long-term dietary exposure to 14 organophosphate pesticides. (Curl et al., “Estimating Pesticide Exposure from Dietary Intake and Organic Food Choices,” Environmental Health Perspectives, February 5, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25650532 ) The scientists found that people who reported eating organic fruits and vegetables at least occasionally had significantly lower organophosphate residue levels in their urine when compared to people who almost always ate conventionally grown produce.

Since 2009, six major meta-analyses have been published comparing the health and safety of organic versus conventional foods. Only two of these considered pesticide residues, and both found that pesticide residues are four- to five-fold more common in conventional food. The six studies also found higher nutrient levels in organic food. A large study published in 2016 in the British Journal of Nutrition found that organic dairy and meat contain about 50 percent more omega-3 fatty acids than conventional products, and a study published in 2014 in the same journal found that organic foods have substantially higher concentrations of a range of antioxidants and other potentially beneficial compounds. (Benbrook, “New Meta-Analysis Identifies Three Significant Benefits Associated With Organically Grown Plant-Based Foods,” July 11, 2014; http://csanr.wsu.edu/significant-benefits-organic-plant-based-foods/; http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/02/18/467136329/is-organic-more-nutritious-new-study-adds-to-the-evidence)

A 2019 study conducted by researchers at the University of California at Berkeley School of Public Health and published in the journal Environmental Research found that families eating a 100 percent organic diet rapidly and dramatically reduced their exposure to four classes of pesticides—by an average of 60 percent—over six days. (Meg Wilcox, “Can Eating Organic Lower Your Exposure to Pesticides?” Civil Eats, February 11, 2019, https://civileats.com/2019/02/11/can-eating-organic-lower-your-exposure-to-pesticides/; Carly Hyland et al., “Organic diet intervention significantly reduces urinary pesticide levels in U.S. children and adults,” Environmental Research, April, 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935119300246)

An April 22, 2022 assessment by the Mayo Clinic confirms that organic foods generally have fewer pesticide residues than conventional, and discusses other potential health benefits from organic foods. Mayo Clinic, “Organic foods: Are they safer? More nutritious?,” Nutrition and Healthy Eating In-Depth, https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/organic-food/art-20043880#

Also keep in mind that some conventionally grown foods are riskier than others See the Environmental Working Group’s 2023 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce, answer to Q. 11. Also check the Beyond Pesticides resource “Eating with a Conscience,” which identifies all the pesticides that can legally be applied to various non-organic food crops in the United States, with links to the health and environmental risk profile of each pesticide. (http://www.beyondpesticides.org/organicfood/conscience/navigation.php)

Probably false. The FQPA was hailed on passage by Commerce Committee Chairman Bliley as a “landmark bipartisan agreement that will bring Federal regulation of the Nation’s food producers into the 21st century.” But the EPA’s response to congressional mandates under the FQPA has been fraught with criticism from the beginning. The long, controversial history of regulation of azinphos-methyl (AZM) is a case in point. AZM, an organophosphate, was used on a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, including “wild” blueberries in Maine, most often under the brand name Guthion. In the late 1990s, a number of environmental and farmworker protection organizations resigned from a top-level EPA advisory committee over dismay at the EPA’s decision not to suspend registration of AZM immediately. The EPA had concluded that dietary risk from food alone for AZM exceeded the reference dose “safe” level for nursing infants and children age one to six in the United States., without consideration of other exposures, such as pesticide drift or the cumulative effects of other similar chemicals. However, it opted for minor changes in use of the pesticide rather than suspending it. The August 2, 1999, EPA press release urged the American public to continue to eat fruit with AZM residues, even before these “mitigation measures” are implemented: “The food supply is safe; this action just makes it safer.” On environmental and worker protection issues, the EPA was somewhat less reassuring: “Azinphos-methyl also poses unacceptable risks to birds, aquatic invertebrates, fish, and terrestrial mammals. It poses a very high risk to aquatic organisms, perhaps the highest among all the organophosphate pesticides. Azinphos-methyl is also one of the most persistent of the organophosphates applied foliarly. The voluntary risk reduction measures should help reduce many of these risks.” The press release also noted that “Azinphos-methyl is hazardous to workers … Estimated risks remain unacceptable despite the use of additional protective clothing, equipment, and engineering controls. Post-application risks to reentry workers greatly exceed EPA’s level of concern.” (EPA, “Azinphos Methyl Risk Management Decision,” August 2, 1999, https://archive.epa.gov/pesticides/reregistration/web/html/azmfactsheet.html)