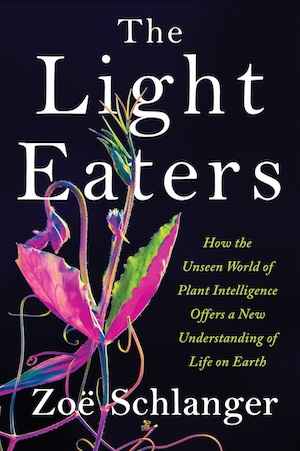

by Zoë Schlanger

Harper, 2024

304 pages, hardcover, $29.99

After being inundated with too many tomatoes this past summer, I told a friend that tomatoes are weeds that have domesticated us. I might not be far off the mark. The idea that rye and other crops entangle us in long-term coevolutionary relationships is just one of the many plant strategies Zoë Schlanger considers in her new book, “The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth.”

We marvel at how fungi create communications networks between trees and the agricultural services of pollinators. Now Schlanger asks us to marvel at how plants, rooted in place, communicate with each other, blend into their surroundings, and trick animals into behaving to their benefit. She takes us into the field and laboratories to meet scientists who are asking questions that, just a few years ago, sounded more mystical than scientific: Do plants have memory? Do they communicate with insects? And how do they make food out of light and air?

As for that last one, Schlanger details the process of photosynthesis in language so delicious that you’ll want to read it more than once. Leaves, she explains, siphon carbon dioxide out of the air through pore-like openings called stomata. Look at them under a microscope and those stomata resemble “small parted mouths, fish lips that open and close.”

One of the topics Schlanger grapples with is how science changes its mind. As an example, she shows how scientists have evolved their thinking about animal intelligence over the past 40 years. They openly discuss ways to test whether bees, crows, and other animals can learn and solve problems. Schlanger wonders if this openness will extend to the plant kingdom. Currently, the idea that plants have memory and consciousness elicits snickers. Plants have no centralized nervous system. On the other hand, researchers have shown that plants can time their flowering to specific windows of bee activity and can increase their nectar production to attract pollinators.

Schlanger devotes two chapters to plant communication — one about how plants talk to each other, one about their conversations with animals. Researchers have shown that when a plant is being nibbled by caterpillars it produces more tannins to make the leaves taste bad to the caterpillars and, in some cases, makes them toxic to the pests. Neighboring plants also produce more tannins in their leaves, repelling caterpillar invasions. How do they know to do this? Nibbled plants release a chemical that alerts other plants of the pest invasion. Some plants, notably corn and tomatoes, go even further. They release “a finely tuned chemical gas” that alerts parasitic wasps who then arrive and lay their eggs in the caterpillars.

Light reading it’s not, but “The Light Eaters” will have you opening your mind to new ways of looking at the plant kingdom that dominates our planet.

– Sue Smith-Heavenrich, Candor, New York

This review was originally published in the winter 2024 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener. Browse the archives for free content on organic agriculture and sustainable living practices.