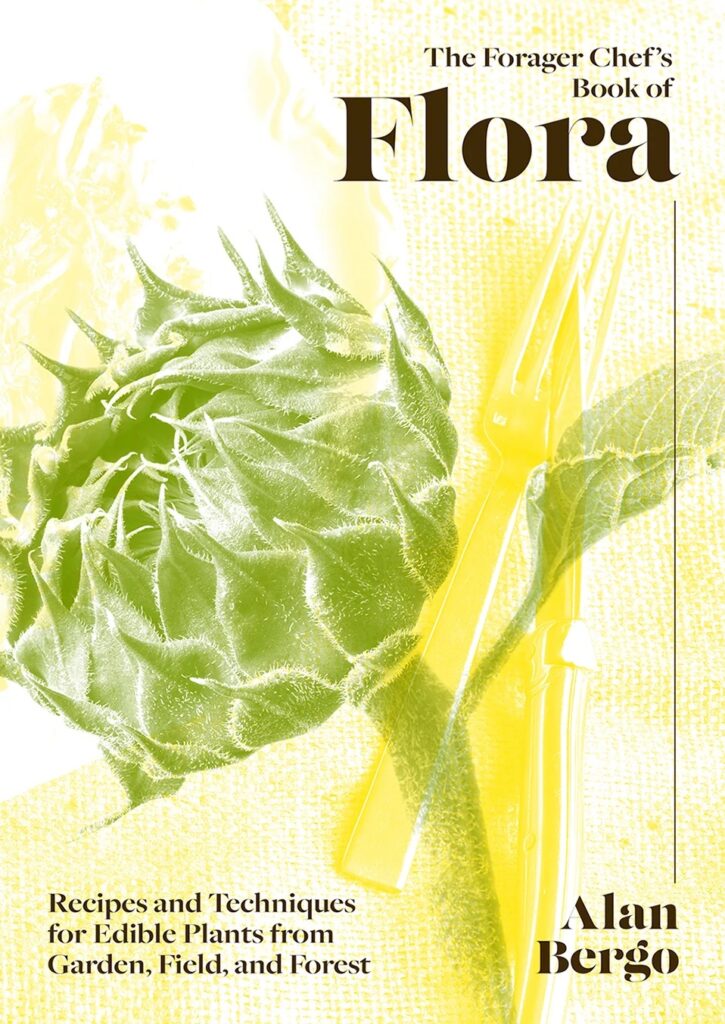

By Alan Bergo

Chelsea Green Publishing, 2021

288 pages, hardcover, $34.95

Alan Bergo’s relationship with food and foraging is influenced by both his background in the culinary arts (he’s worked in high-end kitchens across the Twin Cities) and his insatiable curiosity about the world around him. In “The Forager Chef’s Book of Flora” — which, according to Bergo’s well-known blog, is set to be the first of a three-part foraging series — the author explores plants through observation of the natural world as well as armchair study of anthropology and ethnography.

He writes with candid reverence, “In Italy, entire books have been dedicated to cooking piante spontanee, which translates to ‘spontaneous plants.’” This term, Bergo notes, is more fun than the English catchall for this same category of greenery: “weeds.” And rather than having entire books celebrating cooking these spontaneous plants, as there are in Italy and other places across the globe, Bergo points out that our relationship to weeds in the United States is largely “one of eradication and chemical warfare.” That is not to say that the culture and history of eating wild plants does not exist here — many recipes in the book pay tribute to their roots in Indigenous cultures.

This is not a manual for identifying wild edibles — and Bergo makes it clear that all foragers should proceed with caution (as well as respect). Instead, “The Forager Chef’s Book of Flora,” like most cookbooks, is organized by recipes. He does, however, intersplice snippets of lore and botany along with gorgeous photography throughout.

While this book is intended for seasoned cooks and novices alike, it is without a doubt a book for those who are willing to experiment in the kitchen. While many recipes put to use the usual repertoire of culinary skills — chop, blanche, sauté, etc. — others call for more creative techniques. For example, a recipe for an unleavened corn pastry, the Italian mignecci, details how to use the bottoms of two cast-iron skillets to make a press in which to cook the cakes. (This recipe, along with at least one other, prescribes slightly oversized batches to accommodate for human error.) Though Bergo is quick to offer tips to make the recipes accessible for all. Not interested in awkwardly balancing two heavy skillets over an open flame? No problem. You can fry the mignecci in a skillet instead — though the texture might be different.

Similarly, Bergo lists common substitutes for wild plants in case you’re unfamiliar with a plant, it grows outside your region or it’s out of season. In this way, the recipes have a choose-your-own adventure flare. This thoughtful approach also makes it so you can revisit the recipes again and again, all year long, perhaps trying versions of the “wild greens cake” or “green meatballs” with different combinations of foliage: kale in winter, nettles in spring and so on.

While not a foraging field guide, “The Forager Chef’s Book of Flora,” did introduce me to several plants that I want to get to know better, including sochan (Rudbeckia laciniata). It further tantalized me with thoughts of treating familiar flora in new-to-me ways. I’m excited to introduce cedar cones to my sauerkraut, hosta shoots to my kimchi, angelica stems to my rhubarb crisp, burdock to my mashed potatoes, and purslane to my Panzanella.

These unusual twists bring me to perhaps my favorite takeaway of all: Bergo’s culinary ethos. In the introduction, he writes: “Foraging, in my mind, isn’t just an act—it’s a mindset and a healthy way of life. It’s about the willingness to look beyond the status quo for exciting and unconventional ingredients; an eagerness to make the best possible uses of all the edible parts of plants and animals; and a desire to have a more personal, meaningful, and gratifying relationship with our food.” Bergo inspires readers to not be afraid of the unfamiliar and instead to embrace it (with appropriate care, of course).

Holli Cederholm