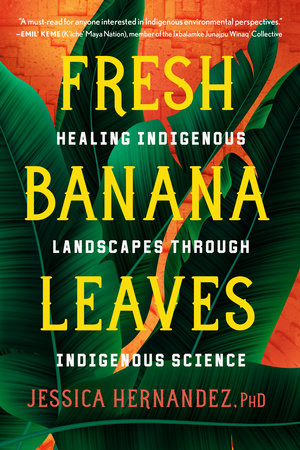

By Jessica Hernandez, Ph.D.

North Atlantic Books, 2022

256 pages, paperback, $17.95

With uncomplicated prose and a distinct perspective, “Fresh Banana Leaves” interweaves a heartfelt narrative about an Indigenous scientist’s journey through academia, and the family and community that have taught her along the way, with a comprehensive primer about the importance of centering Indigenous voices in environmental science and policy.

Author Jessica Hernandez is an environmental scientist of Maya Ch’ortí and Zapotec descent and the founder of the environmental consulting business Piña Soul, which supports Black- and Indigenous-led conservation and environmental projects. In “Fresh Banana Leaves,” Hernandez succinctly and thoroughly introduces a number of ideas important to the intersectional Indigenous environmental movement. Some of these may be familiar to readers with a background in progressive environmentalism, like the fact that local Indigenous tribes should be included in environmental policymaking. Other ideas are likely newer or more radical, such as the Indigenous roots and colonization of permaculture, and the erasure of Indigenous history in the axiom that the United States is a “nation of immigrants.”

Interspersed throughout is the story of Hernandez and her family, and the intergenerational trauma and dissociation from the natural world that is central to their indigeneity. Hernandez also highlights moments in Indigenous environmental movements that are not often discussed in textbooks or newspapers — like the Coast Salish people fighting for fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest during the 1960s “Fish Wars,” and the more recent persecution of the Indigenous Garifuna people in Guatemala over land disputes — as well as featuring voices from current Indigenous-led environmental projects and organizations.

Because of her lived experience, Hernandez’s observations about the hypocrisy of academia are some of her sharpest. She recounts how as a researcher, she and her peers have been told they can study “anywhere in the world,” but “anywhere” often means in impoverished countries, where researchers can effectively helicopter in and collect data without consulting or including local communities. That is not just ethically questionable, she argues — it means that the knowledge gained from generations of research is incomplete, or even erroneous.

True to her background, Hernandez structures her arguments in a straightforward, scientific manner. Like a researcher laying out their thesis and methodology, Hernandez lists the individual points she plans to address at the beginning of new sections and reiterates them throughout. Her prose is intentionally simplistic; she writes that traditional scientific literature is written in a way that is exclusionary, which is one of the many things she hopes to change.

However, the text can be repetitive and some sections could have easily been streamlined.

Still, the power of “Fresh Banana Leaves” resonates, and perhaps most profoundly in its final section. Hernandez mentions how her scientific mentors would poke fun at her incorporation of Indigenous knowledge into her scientific research. They asserted that Hernandez, an Indigenous woman, would have to cite additional research about Indigenous knowledge, often written by white scientists and anthropologists. With this book, Hernandez triumphantly concludes, she has provided an Indigenous voice for the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in scientific conversation — perhaps one that could be referenced by future researchers like her.

Sam Schipani, Bangor, Maine