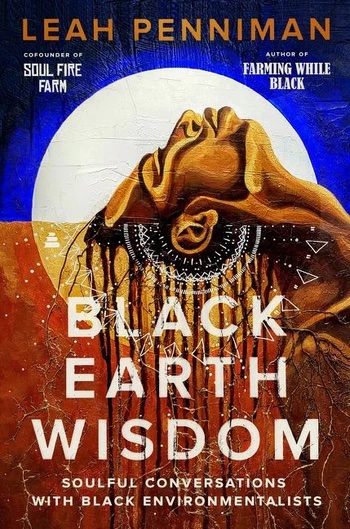

By Leah Penniman

Harper Collins, 2023

352 pages, hardcover, $26.99

With “Black Earth Wisdom,” the brilliant Leah Penniman does something that most successful writers aren’t inclined to do for their sophomore books: pass the mic. In doing so, Penniman has created an essential primer for intersectional environmentalism that should be required reading for anyone who cares about protecting the Earth.

The book is made up of a series of conversations, written in a Q&A style with Penniman leading the interviews. For “Black Earth Wisdom,” Penniman gathered an impressive array of Black intellectuals, writers, activists and more, from late activist Ibrahim Abdul-Matin, to legendary Gullah artist and chieftess Queen Quet, to Pulitzer-prize-winning fiction writer Alice Walker.

Penniman groups the conversations by theme — Spirit, Wilds, Soil, Defense and Witness are the main categories — and pairs (or triples-up) interviewees together under specific topics, such as queerness in nature, Black access to public lands, the relationship between religion and environmental protection, and the link between music and the environment. Penniman’s questions are extremely thoughtful, if over-curated at times, but the wealth of knowledge and perspectives given in the responses are so enlightening that even her most pointed queries are more than forgivable. Penniman prefaces each conversation with either a personal story or an essay contextualizing the topic at hand, or a combination of both. She ends most of the conversations by asking her guests, in some iteration, what they hear when they listen to the Earth. If ingesting multiple sections in a single sitting, this framework could feel repetitive, but it also works to tie the conversations together.

The opening and closing sections of the book are equally impactful. In the preface, Penniman lays out a historical timeline in the form of a Yoruba prayer detailing how the environmentalist ideals of today have originated with or been strengthened by forgotten Black voices, from the African farmers whose techniques laid the foundation for modern permaculture to the stories of activists like Robert Bullard and Hazel Johnson, who are considered the father and mother of the environmental justice movement. The ending includes a Jewish exegesis reflecting on the greater meaning of a rotting log, as well as a poem entitled “Mama Nature Told Me” by Naima Penniman, the author’s sibling. Together, they poignantly connect the overarching philosophy in all the conversations: that human beings are part of nature, and we need to listen to what the Earth is trying to tell us.

The book covers more breadth than depth of any given topic, but that, it seems, is part of the point. Once a reader gets a taste of a voice that resonates with them or challenges their worldview, they can explore more on their own. Certain sections will resonate more with some readers than others. While the conversations about Black land ownership and food sovereignty might be particularly salient for agriculturally-minded readers, I personally learned a lot from the section about environmental justice for communities that rely on aquatic resources. Still, every conversation builds on one another in enough ways that every word feels essential in the end. All together, “Black Earth Wisdom” manages to thread the needle between philosophy, poetry and practical action.

“Black Earth Wisdom” is a book that readers can come back to time and again, to serve as a reference or a guide to even more knowledge by way of introduction to voices often overlooked in the landscape of white-washed environmentalism.

Sam Schipani, Bangor, Maine