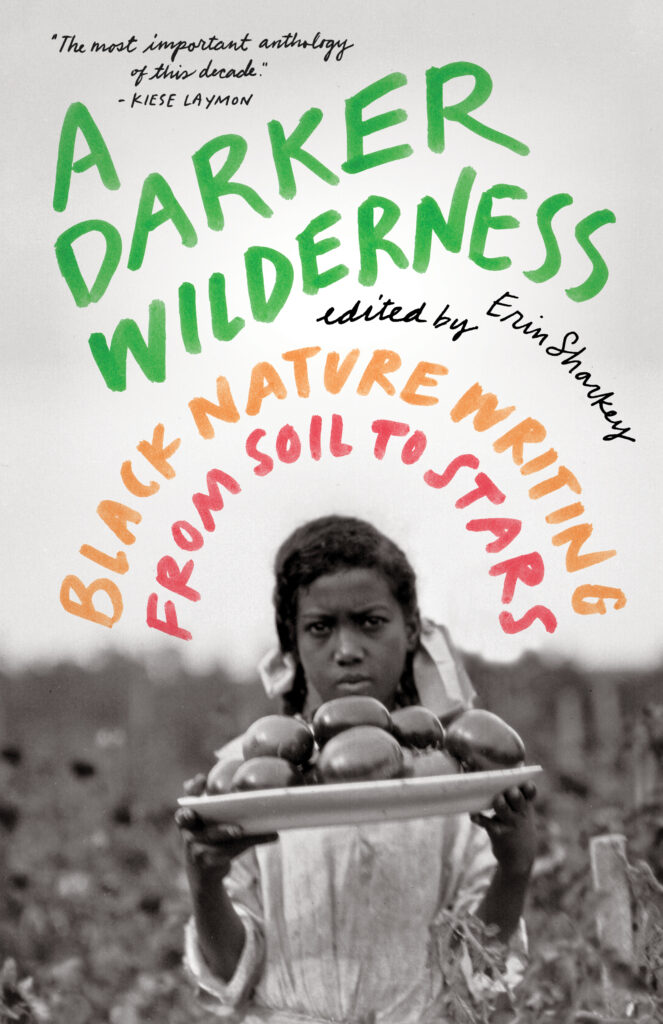

Black Nature Writing from Soil to Stars”

Edited by Erin Sharkey

Milkweed Editions, 2023

312 pages, paperback, $20

For many readers, the idea of “nature writing” evokes elegant prose about living off the land, or taking long treks through mountainous terrain, written by mostly white men and a smattering of heralded women. “A Darker Wilderness: Black Nature Writing from Soil to Stars” flips that paradigm on its head by centering the voices of a range of Black writers. With rich observation and poetic reflection that is characteristic of the form, “A Darker Wilderness” is a collection of beautifully written essays that leads the reader to question what it means to write about — and be a part of — our natural world.

Each essay in “A Darker Wilderness” begins with an image: a scan of a deed dated to the 1760s; the cover of an almanac from 1795; a twisted mermaid sculpture; a photograph of Vulcan’s Anvil, a geographic feature in the Grand Canyon, just to name a few. Structuring the collection this way is not only clever but also helps to ground each essay in a more expansive historical and cultural context that enriches the reading experience.

The writers of the 10 main essays in the collection have a spectacular range of writing styles. Some write straightforward personal essays, and others experiment with form. Some look to the past, others create a guide for the future. The diversity of the essays and the topics that they address is astounding, but the pieces all work together thanks to Sharkey’s masterful curation.

“A Darker Wilderness” aims to expand on what “nature writing” means, particularly in the context of the Black American lived experience. One essay centers on an alley with pockets of nature within a city; another looks at a Black-owned vacation home on Martha’s Vineyard. As is often the case with essay collections, there were certain standouts for me as a reader — I particularly enjoyed Lauret Savoy’s piece about racist language in the names of natural formations and trails, and Sharkey’s reimagining of an “urban farmer’s almanac.” But like all truly great essay collections, the essays that resonate will likely be different for every reader, so it is worth spending time with all of them.

Even so, I confess that, as a frequent reader of so-called “nature writing,” some of the essays didn’t work as well for me within the categorization. Certain essays felt too broad, morphing into more philosophical pieces about “being” in general, and others felt too narrow and introspective, without leaving much room for discussing the relation of the self to the external that feels vital to the genre. However, every time I felt that an essay was not working for me, I was forced to consider why that was. That, in and of itself, felt valuable.

“A Darker Wilderness” is an eye-opening anthology, rich with gorgeous prose, that will bring new perspectives to even the most seasoned reader of nature writing.

Sam Schipani, Bangor, Maine