By Cynthia Flores, Labor-Movement, LLC

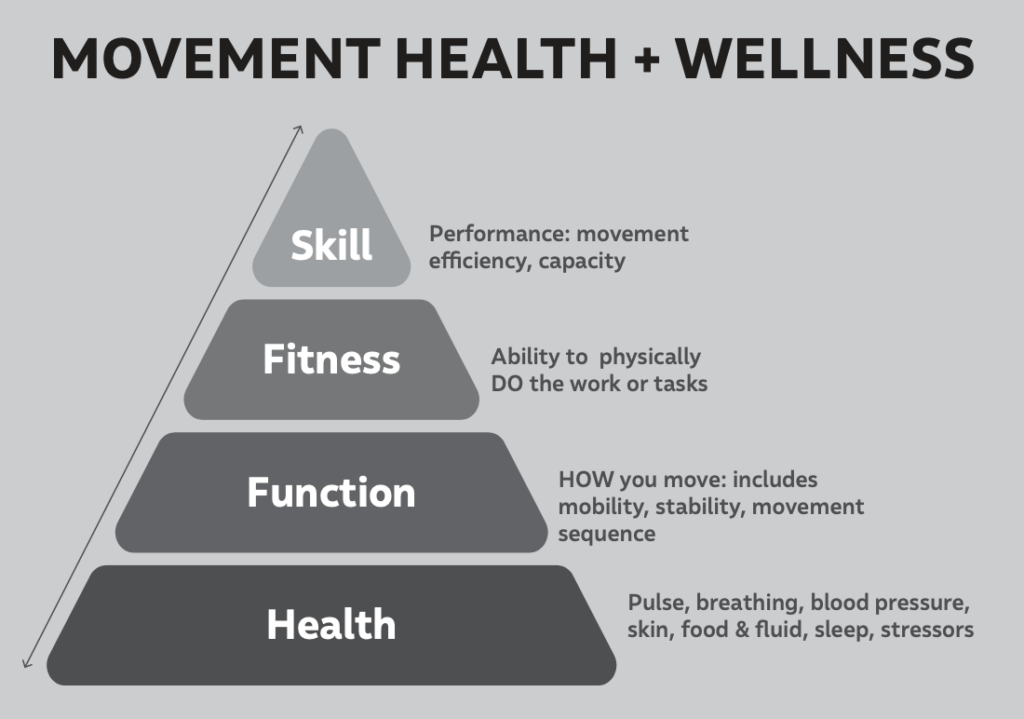

Farmers are athletes. Athletes train for their sport or endeavor. Athletes learn how to move their bodies to maximize strength, movement efficiency, capacity and to reduce injury potential. Farmers, too, can learn about function, fitness and skill to contribute to their health and wellness on and off the field.

Health

Movement health and wellness begins with overall health. Factors include vital signs, such as pulse, respirations, blood pressure and mental status. Other considerations include: food and fluid consumption, electrolyte replacement, accumulated sleep or rest in a day and over weeks, medication interactions, and understanding how stressors and frequency of exposure to stressors may influence mental, emotional and physical health.

Function

Function is how we move. It relates to an individual’s mobility and stability. Mobility is the ability for a joint, such as the shoulder, to go through a full range of motion, both actively and passively. If the arm cannot move up overhead, the primary problem may be reduced shoulder mobility. Stability is the ability to stabilize joints while executing a movement pattern. If the shoulder has overhead mobility, the next consideration is joint stability to lift overhead. Shoulder stabilization includes the arm and torso to maintain normal breathing patterns. Muscle engagement sequence is considered when assessing stability.

Barring any structural or medical compromises, we have full mobility — the range of motion and function of our body and our extremity’s movements. The ability to stabilize relies on muscular contractions and intact neural pathways. Sometimes when there is pain, it is a “feeling of pain” due to stress of actual injury. Other times, the “feeling of pain” is due to brain wiring being messed up. Whether or not an injury is present, the associated pain responses and fluctuations to activity levels can hinder mobility and stability of movement.

Movement is a compromise between what our brain wants to do and our body’s ability to do the task, with or without injury or pain. Our brain will filter down movement pathway possibilities until we accomplish the task. Movement compromise may be a combination of mobility or stability problems, including decreased neural connections or inappropriate sequencing patterns. Movement compromises may occur due to pulled muscles, injury, mechanical constrictions (such as clothing and footwear), working in constrained spaces, and repetitive tasks. Movement compromise for a single occasion may not result in injury, but a compromise may become a movement compensation over time that could lead to problems elsewhere in the body.

When squatting to lift a load, we want our feet flat on the ground and our torso upright (shoulders higher than hips). If, for example, there is decreased ankle mobility, our heels may come off the ground during descent. This movement compromise (between brain and body) allows us (the brain) to complete the task (squatting) within the body’s abilities. If this “heels-up” approach then becomes compromised, the brain may avoid a squat pattern and instead, utilize a “bend at the hips” pattern, dropping shoulders to hip level or below, to accomplish the task.

Another movement compromise that could arise involves shoulder pain or injury suffered from a single event or repetitive motion tasks. The shoulder is a complex of muscles, tendons, ligaments and a joint capsule that allows for flexion, extension, rotation and more. If there is pain or decreased range of motion, a movement compromise might include shrugging the shoulders to complete an overhead or reaching task. Left unattended (without mobility exercises, strength exercises, soft tissue work and/or advanced care) this movement compromise could become a movement compensation that then may affect neck and shoulder muscles, alter breathing patterns or cause low back or hip pain.

It is not uncommon for altered movement patterns to cause chain reactions elsewhere in the body. Does your knee hurt because it is injured, or does your knee hurt because of decreased ankle mobility and an altered gait?

Fitness

Without health and function, it is generally more challenging to gain or maintain fitness and skill. Fitness is our ability to physically do the work or tasks. Fitness levels change over the course of a farm season and the experience of multiple years. Fitness in the spring might feel different than in the fall due to repeated exposure to workload and stresses.

Similar to new or returning athletes, considerations for new or returning farmers, such as an onboarding type workload, may encourage longevity by allowing time to maintain or adapt health strategies. Such strategies aren’t just employed in the field — farmers need to lay the groundwork for health at home, including setting aside time for meal prep, laundry, sleep and outside work activities. Gaining fitness by onboarding might also give farmers an opportunity to learn how to move efficiently — especially if farming is new. Finding ways to decrease physical and potential mental stress and allow for acclimatization at the beginning of a season might mitigate the chance of reoccurring aches, pains or injuries mid to late season.

Skill

Skill development is often overlooked in relation to movement health and wellness in farming. Such development should include not only how to be efficient and productive farming, but also how to move one’s body efficiently and effectively. Classes exist to learn how to tend the land, succession plant, cultivate and harvest, operate machinery, and tend to livestock. Often physical ability is assumed, and skill development focused on body mechanics and movement patterns as a risk management tool for injury prevention and career longevity is neglected.

Movement pattern skills for farming include maintaining a neutral spine when picking up, putting down or moving in rotation with a load of significant weight relative to the individual. Maintaining a neutral spine, that is no bends in the back other than naturally occurring curvature, along with core engagement, helps protect the back for repeated lifting and lowering of various loads. How to maintain a neutral spine is one of the first things a strength athlete learns. Swimmers learn breathing patterns and body rotation for efficiency. Driving a tractor to plant or harvest, or loading a market truck, both require body rotation. Exhalation during rotation is a way to decrease neck, shoulder and back pain. Likewise, pitchers learn how to throw, and tennis and golf athletes learn how to grip and swing their racquet or club. Throwing hay bales and milking require shoulder maneuverability. Shoulder packing and lat muscle engagement allow bigger muscles from the torso to be effective. In repetitive hand-intensive work, such as clipping and stripping flower stems, farmers could benefit from understanding grip patterns, including hand flexion and extension, lower arm rotation and shoulder engagement.

Farmers are athletes. But unlike in athletics, in agriculture movement patterns and body mechanics are often not considered until there are aches, pains or injuries, both acute and chronic.

Farmers are athletes who perform during countless hours, endless days, and longer and longer seasons. The number of squats, hinges, pushes, pulls, rotations and lifts with variable loads performed in a single day, without adequate rest periods, exposes farmers to possible function or health concerns. Sports athletes have a limited season of play, typically weeks to a few months, followed by an off-season. Many farmers have very limited off-season time.

Farmers are athletes. Movement health and wellness begins with health. The health of a farm relies on the health of the farmers, including physical, mental and emotional well-being.

Labor-Movement, LLC strives to be a resource, educator and coach to farmers, foresters, tradespeople and industrial athletes, to improve body mechanics and movement patterns for injury prevention, increased efficiencies, and longevity in a day, season or career.

This article was originally published in the winter 2022-23 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.