|

| Strawberries growing in a matted row system. MOFGA file photo. |

David Handley, UMaine Extension small fruit and vegetable specialist, and David Pike, who grows strawberries in Farmington, Maine, talked about this crop at MOFGA’s November 2011 Farmer to Farmer Conference.

Handley noted that aside from wild blueberries, strawberries are the most popular berry grown in Maine; the most popular pick-your-own crop here; they have a reasonable labor requirement, require a relatively low investment, and have a high potential return per acre. Vegetable and strawberry production use similar tools and knowledge.

Systems

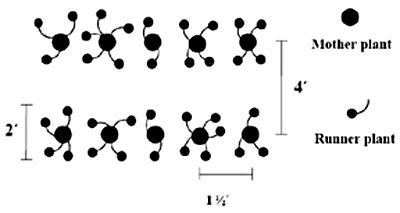

Most Maine growers use a matted row system: Plants are set and allowed to send out runners that produce a bed full of plants.

The alternative, plasticulture, involves setting plants closer together through black plastic mulch, usually on raised beds, and removing runners.

Because organic growers don’t use the herbicides that conventional growers do, they tend to rotate out of strawberries in a two-year cycle (a planting year and a fruiting year) to control weeds, rather than the conventional three to five years. So organic growers must plant annually to maintain production.

Handley and Pike talked about both June-bearing and daylength neutral strawberries.

Plant Morphology

Handley explained that this herbaceous perennial has a crown – a compressed main stem – with different types of buds to form leaves, flowers, runners, branch crowns (small crowns branching off the side of the plant) or roots, depending on daylength, temperature and where buds are on the crown. Primary buds at the tip of the crown form leaves until short fall days and cool temperatures induce them to produce branch crowns and flower buds, which overwinter and produce fruit the following spring. A plant with more branch crowns produces more flower stalks – good to a point; but with more than three or four branch crowns, fruit will be smaller.

Fruiting potential depends on yield per plant, number of plants per acre (although too many plants will create competition, impairing quality) and variety.

Sites and Soils

Strawberries do best on a well drained soil with more than 2 percent organic matter and a pH of 5.8 to 6.5; with full light exposure, a gentle slop (8 percent maximum; and not at the bottom of a slope or in a frost pocket) and slight elevation. Having water nearby helps with irrigation and frost control.

Eliminate weeds before planting, and do not plant where nightshades (potatoes, tomatoes, eggplant or peppers) grew within three years, since these can carry the soil fungus Verticillium, which attacks strawberries.

Incorporate needed amendments (including lime or dolomite if needed; strawberries have a high demand for magnesium) before planting.

After growing strawberries, that ground should grow another crop for four to five years. Good summer rotation crops include grasses, legumes, buckwheat and non-nightshade cash crops; winter rotation crops include winter ryes and mustards; the latter, planted as late as September and incorporated in spring a couple of weeks before planting strawberries, helps reduce weeds and soilborne diseases.

Matted Rows

To plant matted rows, order dormant crowns by January 1. When they arrive, check for healthy yellow roots (not black, rat-tailed or moldy) and firm white crown tissue.

By mixing early, mid and late-season varieties, the harvest season can be three to four weeks longer – possibly even longer using row covers.

Popular early varieties are ‘Sable,’ vigorous plants with some resistance to red stele, with medium to large fruit, very good flavor, high yield potential, a long picking period, but soft fruit that may decline in size sharply after the first harvests; and ‘Wendy,’ vigorous plants with an early berry with good color, firmness and flavor, very good yield, later flowering than some other early varieties, with some tolerance to red stele but some problems with leaf spot.

Popular early to midseason varieties include ‘Honeoye,’ vigorous plants that produce many runners and high yields of large, very attractive, firm fruit but possibly a tart to flat flavor; plants are very susceptible to red stele and Verticillium and don’t tolerate wet feet, so they do better on raised beds; and ‘Brunswick,’ vigorous, high yielding plants with medium to large, blocky, attractive, dark red, somewhat tender fruit that may be tart if not picked fully ripe; these have some resistance to red stele.

For midseason, growers like ‘Cavendish,’ moderately vigorous plants with high yield potential of large, firm, flavorful fruit that ripens unevenly. “Convince people that even if fruits have a little white on them they are still flavorful,” said Handley. These resist red stele and Verticillium but not gray mold, especially when flowering in a wet spring. ‘Jewel’ is moderately vigorous with very good yields of large, glossy, attractive, firm fruits; it is susceptible to red stele, Verticillium and winter injury, especially in an open, northern Maine winter.

Mid to late-season varieties include ‘Cabot,’ which needs good soil fertility and a dry area to produce its very large (eight berries per quart), rough, bright red, firm fruits with tender skin; it is susceptible to gray mold; and ‘Mesabi,’ a vigorous plant with good yields of large, attractive fruits that may be difficult to spot under the foliage; this variety resists red stele and leaf spot, so is good for less-well-drained clayey soils.

‘Valley Sunset,’ the favorite late season variety, is very productive over a long period and has large, attractive fruit with good color and firmness.

Set plants in a trench (or use a bulb planter) at a depth of about halfway up the crown, in April or May, as soon as the soil can be worked without harming it. Don’t plant much after June, since plants weaken in storage, and plants set late are more easily heat stressed. Mechanical transplanters, including a potato planter, can speed transplanting.

For matted rows, set plants in 4- to 12-inch-high beds that are 1 to 2 feet wide; space plants 1 to 2 feet apart (close for less vigorous varieties; wider for more vigorous); space rows 42 to 60 inches apart. This requires 7,000 to 8,000 plants per acre. (Plasticulture, covered below, may use up to 18,000 plants.)

Water plants in and water them often as they become established. Trickle irrigation buried 3 inches deep is popular, especially on raised beds, but will not protect against frost as overhead can.

Cultivation tools include Buddingh finger weeders for very small weeds, Reggie weeders against bigger weeds, and Lely cultivators after plants have well established roots and before they runner.

About a month after planting, when tissues are soft, pinch flowers clusters out with your finger and thumbnail at the bud stage, three or four times over two to three weeks. Waiting longer requires clippers and takes longer. Removing flowers encourages runners to grow, reduces plant stress, and reduces disease potential, since no fruits will grow this year and leave overwintering disease spores behind.

Runners emerge from July to mid-September, rooting between mother plants. Let four to six runners root around each mother plant. Attention to soil moisture promotes rooting.

Rows should ultimately be 2 feet wide, with only primary runners (not secondary or tertiary runners coming from other runners; remove these with a hoe). Hold runners that grow out of the bed back in place in the bed with rocks, hairpins, etc. Remove late-produced runners.

Most fertilizer is incorporated before planting. An early to mid-August application of about 20 pounds of nitrogen (e.g., from Chilean nitrate, fish meal, alfalfa meal) per acre over plants may help as plants finish setting runners and start producing flower buds. Control weeds all summer.

When plants are dormant (usually between Thanksgiving and the second week of December, when leaves are red and wilted), apply 6 to 10 inches of mulch for winter protection. Use 3 to 5 tons per acre of non-weedy straw (not hay, which has weed seeds). Sawdust or shavings work but are harder to apply and to remove in spring; are not as nice to walk on as straw in paths; require added nitrogen (N) to compensate for their high carbon content; and may encourage Phytophthera root rot. Leaf mulch won’t break down enough the following year and can keep the soil too cold and wet. Pine needles can work.

In the second year, in late March or early April, move mulch into walkways and under and around plants. Leaving it on plants later can reduce frost problems but will also reduce yield – although a little left in the bed can keep berries cleaner.

Some growers fertilize with 10 to 20 pounds of readily available N per acre in the spring, but excess N will produce many tall leaves that cover flowers and fruits and promote rot. Phosphorus, calcium and boron – nutrients critical for flower and fruit production – should be readily available in spring.

Beginning in spring, watch for fruit rots, tarnished plant bugs (TPB), strawberry clippers and weeds. Keep plants dry but irrigated.

For frost protection, sprinklers should be about 24 inches high, have frost nozzles and cover the planting without soaking the field. Turn them on when the temperature at bud height is 33 F; turn them off when ice that formed on plants has melted. Frost injured flowers turn black in the center and will not produce fruit.

Harvest berries from mid-June to mid-July, starting three weeks after bloom, when they’re fully ripe. Pick regularly and often to minimize the number of rotting fruits staying in the field. Irrigate between harvests in dry springs.

Have neat, easily read signs that clearly tell pick-your-own customers where to go; have plenty of parking, field access free of hazards (drainage ditches, irrigation pipe, farm machinery) and transportation to fields. Post picking rules and instructions. Never allow pets in the field, for food safety reasons. Have plenty of picking containers, clean restrooms with handwashing stations, shade, seating and drinks. Let your insurance agent and, possibly, local police (because of potential effects on traffic) know what you’re doing.

The biggest complaint about pick-your-own operations and farmers’ markets, said Handley, is waiting too long in line, so have friendly, fast, efficient checkout personnel.

If you plow under strawberries in the second year, you can then plant a late vegetable crop.

Some organic growers try for a third-year harvest, but plots are usually too weedy then to be productive. Flame weeding may help control weeds enough that a third year is possible.

If you are going to renovate (i.e., if weeds are under control), remove in-row weeds by hand or with a hoe. Between mid-July and early August, mow strawberry plants about 2 inches above the crown with a flail mower, weed whacker, etc., to remove leaves and stimulate new vegetative growth and to enable fertilizer to get into the soil. Don’t mow if plants are stressed from drought or other factors. Apply N, P and K based on a soil test – usually about 30 to 40 pounds N per acre.

Till the sides of the rows, narrowing rows to 10 inches. Throw about an inch of soil over the remaining crowns, since they tend to grow out of the ground over time.

Alternatively, a reduced or no-till renovation can reduce weed pressure. Mow and fertilize, then, to narrow rows, flame weed or apply a contact herbicide, such as an acetic acid product approved for organic use; use a shield to protect strawberry plants. Some growers plant a cover crop between rows. Then water the planting and continue weed and runner control all summer with an organically approved herbicide or flaming. This no-till approach does not throw soil over plants; you could apply compost to cover roots that appear as crowns grow out of the soil, but doing this at Highmoor Farm resulted in excess soil fertility.

|

| Strawberry spacing in matted rows (above) and in a day neutral planting (below). From “Growing Strawberries,” by David Handley, UMaine Cooperative Extension, https://umaine.edu/publications/2067e/ |

|

Annual Plasticulture for June-Bearing Strawberries

Instead of matted rows, strawberries can be grown on plastic covered beds, from dormant crowns or from plugs.

From Crowns

Dormant crowns, about half the cost of plugs, are planted in June or July (later than for matted rows). Many varieties are available, and disease is not a big issue, but heat stress can be.

In year one, prepare the soil and beds, apply trickle irrigation, then mulch (generally with black plastic; check with your certifier about how long the plastic can stay in place).

David Pike uses a single-row bed shaper to make beds that are about 5 inches high. Two rows of 15 ml drip tape with 12-inch emitter spacing run down each bed, under plastic mulch.

Between the plastic rows, Pike sows dwarf perennial ryegrass before he punches holes in the plastic mulch for the strawberries to ensure that the grass doesn’t get into the planting hole. He mows the grass with a rotary mulching mower periodically. To control grass along the edge of the plastic where he can’t mow, he has used long-handled shears and, at times, herbicides with a shielded applicator. (Pike is not certified organic.) Between mowing the grass and mulching with plastic, some 90 percent of the ground won’t produce weeds. He’d like to try landscape fabric between plastic strips.

Grower Nate Drummond once sowed a red clover winter mulch between his rows, but it winterkilled. Now he uses landscape fabric.

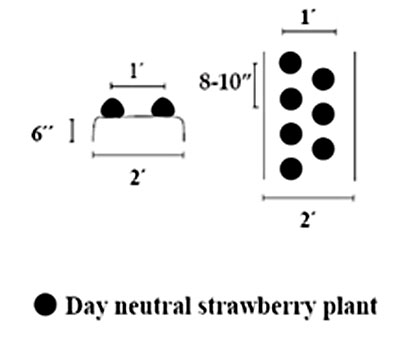

Handley recommended planting double rows of crowns 10 to 12 inches apart, through the plastic. Pike uses a two-row punch wheel machine, with baseball cleats screwed into a wheel and centering guide wheels, to make small dimples rather than holes in the plastic, in two rows 24 inches apart, with dimples 9 inches apart within rows for June-bearers (‘Cabot’ and ‘Honeoye’) or 13 inches for day-neutrals.

“Row edges produce,” said Pike. His two rows per bed have four row edges, which will out-produce a big matted row.

The baseball cleats make such small dimples that soil doesn’t get muddy during rains or dry out during droughts.

Pike uses a strawberry planting tool developed in North Carolina to set the plants. (See www.smallfruits.org/Strawberries/production/strbry_Settingplantswithahandtool.pdf)

For June-bearing strawberries, he soaks dormant bareroot plants in a transplant solution of SeaCure and Agri-Gel (not approved for organic production), then transplants them around June 22 so that they establish three or four branch crowns but few runners.

Pike warned growers not to put composted chicken manure or other fertilizer in the planting hole with the strawberry plant, but to place it a couple of inches away (possibly in a hole made with the planting tool) to prevent burning plant roots.

In May and August, Pike injects 250 million parasitic Hb nematodes per acre through the dripline to counter strawberry root weevils. He buys nematodes from Koppert in Michigan for about $90 per acre – much less than from The Greenspot in New Hampshire, said Pike.

Handley advised removing the filter from overhead irrigation when applying nematodes that way (which you wouldn’t, if plants were on black plastic). Also, make sure the soil is moist so that the nematodes survive.

Remove flowers and runners from July through September. Pike uses long-handled edging shears to cut runners during establishment and renovation. (Some people let plants fruit the first year; yields won’t be high, but if pickers are available, this can be worthwhile.)

Handley recommended covering plants with row cover in September or October (a cost of $800 to $1,200 per acre). Straw mulch is difficult to apply and tends to blow off plastic. Some of Pike’s floating row covers have lasted more than 10 years. This minimizes weed seeds that might come in, even with straw, and the lower weed pressure enables three harvest seasons if he renovates. By the third or fourth year, few runners are being produced.

To apply row cover by himself, Pike unwraps the 1.2-ounce material from a wooden spool that electrical wire comes on. He secures the fabric every 12 feet with mesh bags holding rocks. The bags come from Paris Farmers Union via Berry Hill Irrigation in Virginia. Pike ties a knot in one end of the bag, puts in 5 or 6 pounds of round (not sharp) rocks, ties another knot, puts in more rocks, then ties the end, making a “handle” in the middle. He stores these rock bags outside on a pallet until he needs them in the fall. A 35-foot-wide fabric covers five 6-foot-wide beds, said Pike. It should last three to five years, so the $600 per acre for the fabric, $200 for the rock bags, and, each year, $100 for labor makes this system more economical than using 400 bales of straw per acre annually at $2 each, plus the labor to apply and remove it.

Remove row covers in April or May. Pike pulls his back as soon as the snow melts to delay production until kids (his labor) get out of school. He sweeps dead debris off with a hydraulic broom and sets up overhead irrigation for frost protection.

Harvest in June and July, then remove the plastic, plow down the crop and plant a rotation crop.

If your certifier allows, consider keeping plastic down for another year. North Carolina growers found that these plants produce so many branch crowns that fruit size and quality decline tremendously, and diseases are very difficult to control; but for Pike, plants with 10 or 12 crowns still produced good fruit size.

To renovate, Pike mows with a modified rotary mower, cuts runners with long-handled edging shears (which takes 40 hours per acre), and sweeps clippings off with a hydraulic broom. With the plastic still in place, any added nutrients come through drip irrigation or from foliar sprays.

From Plugs

Plugs come from runner tips clipped from mother plants, grown under mist in a greenhouse for three to four weeks and set in the field in late summer. Plug plants are expensive, not as available as crowns; only limited varieties, such as ‘Chandler,’ are available; and many come from the South – already diseased.

Pike grows his own plugs by harvesting runner tips with scissors around August 1, setting them in trays right away and keeping them under mist outdoors (or putting them in the refrigerator until he has time to put them in planting media). He keeps them moist until they’re rooted, then cuts back on watering. Handley noted that growers cannot legally propagate patented varieties.

If using plugs, prepare the ground and apply mulch in spring or summer. Plant plugs in late August or in September through the plastic and water them right away.

Flowers and runners usually don’t have to be removed, since few grow from such late plantings, although one grower at Farmer to Farmer did have runners grow; Handley said to remove them in that case.

Provide winter protection (usually fabric row covers) in September or October.

In year two, remove row covers in April or May, providing frost protection when necessary.

Harvest berries from June through July.

Then remove the plastic, plow down the plants and plant a cover or rotation crop.

Day-Neutrals on Plastic

“People say day-neutral strawberries taste so much better than June and July bearing plants,” said Pike, adding that they hold in the refrigerator for at least a week.

Three to five months of fresh strawberries are possible in Maine by growing day-neutral varieties. By combining June-bearing and day-neutral strawberries and using hoops and floating row covers, Pike said that “last year we had fresh strawberries on our table for about six months.”

Pike likes ‘San Andreas’ and ‘Albion’; ‘Seascape’ did well initially but then dropped off; other varieties available include ‘Monterey,’ ‘Portola’ (which he will not try again) and ‘Evie-2.’

To grow day-neutral varieties from crowns – almost all that’s available here – with annual plasticulture, prepare the ground and apply mulch in fall or spring; plant through the plastic in May or June; remove flowers for four to six weeks; remove runners from July through September; and harvest from August through October or, with row covers, into November.

Day-neutrals like a cool climate, so Pike sprays his black plastic with calcium carbonate around July 2. Most washes off with rains to expose the black plastic by late summer or early fall. He hasn’t determined the effectiveness of this practice yet.

To extend the season, Pike sets wire hoops ($3 each from Johnny’s) 10 feet apart in early September. When cold nights are forecast, string baler twine between hoops helps support the 1.2-ounce fabric row cover and anchors it at the ends, and mesh rock bags hold the row cover edges down; this should provide protection to about 20 F. The row cover also sheds water during storms; less water going on plantings means fewer soft berries produced.

This year Pike is trying low tunnels to extend the growing season. Every 5 feet along the ridge line, mist nozzles apply foliar fish emulsion and, at times, Oxidate for disease suppression. Pike will remove the tunnel and apply floating row cover for the winter to prevent the plants from growing then. Next spring he’ll replace the hoops, harvest a crop, renovate after the spring harvest, then next fall take the tunnel down again. He’ll pull or kill the plants next fall, then replant, getting two more years out of the black plastic mulch. (Check with certifiers before leaving mulch down so long.) The tunnel should pay for itself in four years. In the second season, an early spring crop with day-neutral berries under floating row covers and hoops will produce before June bearers. If you can keep the plastic on, you won’t lose crops due to heavy rains, said Pike.

In the second year, after the early harvest, Pike mows day-neutral plants – even if they still have berries on them – as soon as the June-bearers come on. This allows day-neutral plants to regrow and produce soon after June bearers finish. Pike sweeps plant residue into the row middles; it decomposes when he mows with a mulching mower.

To double crop day-neutral strawberries, Pike plants in fall, harvests the following spring, renovates, and then harvests a summer and fall crop from the same plot.

He kills plants in early November. Early the following spring, he replants between where the old plants were. This eliminates preplanting costs; increases profits for the life of the bed; and enables early planting.

Pike picks day-neutral berries over three months in late summer to early fall, peaking in September. He gets 0.6 to 1 quart per plant, or 10,000 quarts minimum over three months. Some days he picks 100 quarts on 1/4 acre; some days 40 to 50 quarts. Plants produce well from mid-August through September and slow down in October, when a week may pass between picking any given plot.

Bottom Line

Penn State, said Handley, shows establishment costs for a conventional matted row system of $2,500 to $4,000 in years one and two, and maintenance after that at $6,500 to $8,000 per acre, mostly for harvesting and weeding.

Net returns from a matted row range from $2,000 to $6,000 or more per acre, depending on yield (usually 5,000 to 10,000 pounds per acre; some get much more) and price (usually $0.90 to $1.50 per pound). In some affluent areas, growers get $5 or $6 per quart (1.5 pounds). Handley said economic figures vary widely with producers and markets.

Pike presented hypothetical costs for day-neutrals of $13,400/acre for plants; $12,000 for establishment; and $9,000 for harvest. At 0.8 quarts per plant and $4 per quart wholesale, gross profit is $42,800 and net is $21,880.

In early summer, Pike sells about 600 quarts per day from his roadside stand. In August he could sell 100 quarts per day of day-neutral plants. As people get used to the idea of having strawberries for a longer season, he believes growers will be able to sell more day-neutrals. Growers should get $5.50 to $6 per quart retail, he said.

One grower raised strawberries on plastic with row covers and sold 100 to 200 pints per market at $4 each at the Brunswick Farmers’ Market two weeks before other growers who used matted rows. Some customers bought more than 20 pints to process, even at that price.

Another said day-neutral berries did not sell well at the Portland market. Pike said that customers may not believe that such early berries are local.

Yet another said that early and June-bearing strawberries work great on his farm because little vegetable harvesting occurs then, and the berries allow him to hire a full crew earlier in the season. But the vegetable harvest that comes later is so time-consuming that later-producing day-neutrals didn’t work for him.

And yet another said that picking strawberries interfered with weed control on the farm.

Insect Control

Pike said that his day-neutral plants produce a spring crop before strawberry clippers arrive; and a couple of sprays of Pyganic in late August and early September control them then.

Handley said that tarnished plant bugs (TPB) peak when day-neutrals come into production. Row covers stop the adults from laying eggs, and netted row covers (e.g., ProtekNet from Orchard Equipment and Supply in Mass. or from DuBois Agrinovation in Quebec – www.duboisag.com) are probably effective against TPB, Handley added, if applied before adults lay eggs – in spring for June-bearing plants and as soon as plants start to flower for day-neutral.

“As long as there’s good wind movement, strawberries are self-fertile and don’t need pollinators,” Handley added, so they can be covered.

Disease Control

Handley recommended using Oxidate – a peroxide sanitizer, with some formulations OMRI-approved for outdoor use – to protect plants at bloom and when rain or fog is present, when Botrytis spores germinate. Oxidate burns existing spores but must be reapplied to be effective. A row cover that sheds water also helps protect plants, if temperatures aren’t too high.

Oxidate is very corrosive, so wash sprayers after applications to preserve nozzles, said Handley; and MOFGA’s Cheryl Wixson said to protect your skin when using it too.

Serenade, said Handley, reduced Botrytis infection from 100 to 75 to 80 percent.

Bicarbonates were almost ineffective against Botrytis but can help fight powdery mildew.

Copper, applied at bloom, offers some protection, but check the label for days to harvest, said Handley. Pike cautioned growers not to burn plants with copper. Another grower noted that copper can accumulate in heavy soils. And certified growers using copper need to test their soil to make sure it’s not accumulating, said Jacomijn Schravesande-Gardei of MOFGA Certification Services LLC.

Since Botrytis overwinters on dead and decaying vegetative material, spring cleanup helps, as does Oxidate applied in the fall, before mulching, to burn some overwintering spores. At UMass, fall flaming increased Botrytis in some cases, possibly by wounding tissues so that the disease survived in plants.

One grower noted that raised beds and well spaced plants encourage air flow, which helps control disease.

Removing diseased tissue from the field helps too, as does avoiding standing water in the field. Turf between the rows absorbs excess moisture, said Handley. Dave Pike’s beds are slightly crowned so that water rolls off the plastic, away from strawberry plants.

Deer

Grower Nate Drummond said that deer and mice are his biggest pest problems, while they don’t bother a neighbor’s matted row strawberries. Drummond puts up electric fencing as soon as strawberries are planted and keeps them on all fall. Deer also trample plastic.

Another grower uses two rows of electric fencing, putting strips of foil coated with peanut butter on the fencing to train the deer. This worked for years, but wasn’t foolproof last year, “the worst year for deer ever.”

Strawberry crowns are full of sugars that deer want, Handley explained. He said that Tiger Industries of Rhode Island has a new fish oil-based deer repellent that is said to last for six weeks; Handley is trying it at Highmoor Farm this year.

Another grower said that rotted egg yolks deter deer.

Mice

Drummond uses two layers of row cover in winter, which attracts more mice, so he traps mice. Every mousetrap is flagged, and every time workers picked, they also check the traps.

Another grower roots out mice, harassing them with sticks and water, as close as possible to the time the ground freezes hard so that they won’t nest in the area.

Handley suggested making mice expose themselves to predators as much as possible by cutting grass low around the planting and using landscape fabric between rows.

Birds

Cedar waxwings love strawberries. Handley said that netting keep them off plantings.

To frighten crows, one grower runs a row of flash tape down the center of the bed, supporting it on stakes about 6 inches above plants. Grower Jan Goranson runs VHS tape in a random pattern on high stakes.

“Birds hate to have something over their head when they’re pecking,” Handley said.

Handley noted that songbirds are protected, so you need a permit from APHIS (which takes about 8 months to get) to shoot them, but shooting probably won’t work very well. Having numerous trees and power lines around increases the problem. Handley heard anecdotally that placing strawberry-size rocks painted red between strawberry rows in spring, before berries turned red, will fool birds, which will give up on the plot.

Resources

Cornell Berry Diagnostic Tool, www.fruit.cornell.edu/berrytool

New England Small Fruit Pest Management Guide, www.umass.edu/fruitadvisor/nesfpmg/index.htm

Strawberries: Organic Production, ATTRA, https://attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/summaries/summary.php?pub=13

“Strawberry Production,” Penn. State (includes enterprise budget sheet),

https://agalternatives.aers.psu.edu/Publications/Strawberries.pdf

Strawberry Production Guide for the Northeast, Midwest and Eastern Canada, NRAES-88, $45, www.nraes.org/nra_order.taf?_function=detail&pr_booknum=nraes-88

“Strawberry Varieties for Maine,” by David T. Handley, https://umaine.edu/publications/2184e/

“Strawberry Variety Performance in New England,” by David T. Handley, Mark G. Hutton and James F. Dill at https://newenglandvfc.org/pdf_proceedings/2009/SVPinNE.pdf

David Handley: [email protected]

David Pike: [email protected]

– Jean English