By Will Bonsall

Ecoefficiency is a word that I once coined, only to learn later that it was already used in a somewhat different context. For me, it encompassed many ideas implied by “organic,” “sustainable” and “natural.” Basically, the term assumes that every living organism, be it mushroom, palm tree, gerbil or giraffe, requires a certain amount of “life-stuff” (including soil, water, air, sunlight, whatever) to become itself, and that the organism in turn releases that stuff when it dies, rots, is eaten, etc. The ratio between those two things (call them “input” and “output”) is what I mean by ecoefficiency.

Here is a simple example: fallen maple leaves add much more goodness to the soil than what it took to create them, whereas pumpkins require a lot more life-stuff to create them compared to what their rotting carcasses (roots, vines, fruit and all) return to the soil. We can confirm that by browsing through the green manure section of a seed catalog. Notice you will see no pumpkins (nor Brussels sprouts, nor leeks) listed there. Those are planted to feed our bellies, not the soil, and there’s a good reason for that. You see, most of the vegetable foods on your plate are what I call “Band-aid species” — nature’s quick fix for ecosystem disruptions like disturbed soil. When the earth is exposed as by fire, flood, hooves or cultivation, nature has an array of plant species held in reserve which immediately germinate and proliferate to cover and protect the soil as swiftly as possible. Those plant species, mostly quick-growing annual and biennial “weeds,” are succulent and digestible (to humans and/or other animals), which is how they (or rather their selected descendants) ended up on our plates. However, these plants tend to not be very eco-efficient; after all their ecological role is not long-term maintenance and building up of the soil but merely to provide a stopgap until the real soil-builders can become established.

And what are those? The perennial grasses, woody shrubs and, ultimately, trees that last. This is why all the climax communities (also known as biomes) on the planet are forests, with one major exception: grasslands/prairies/savannahs. If only we could eat directlyfrom the forests (the ideal of permaculture), we would have the ultimate eco-efficient agricultural system (which is why chestnuts and acorns are so exciting). As for eating from forests indirectly, by feeding forest products to animals and then eating those, that largely negates the biggest advantage of permaculture: ecoefficiency.

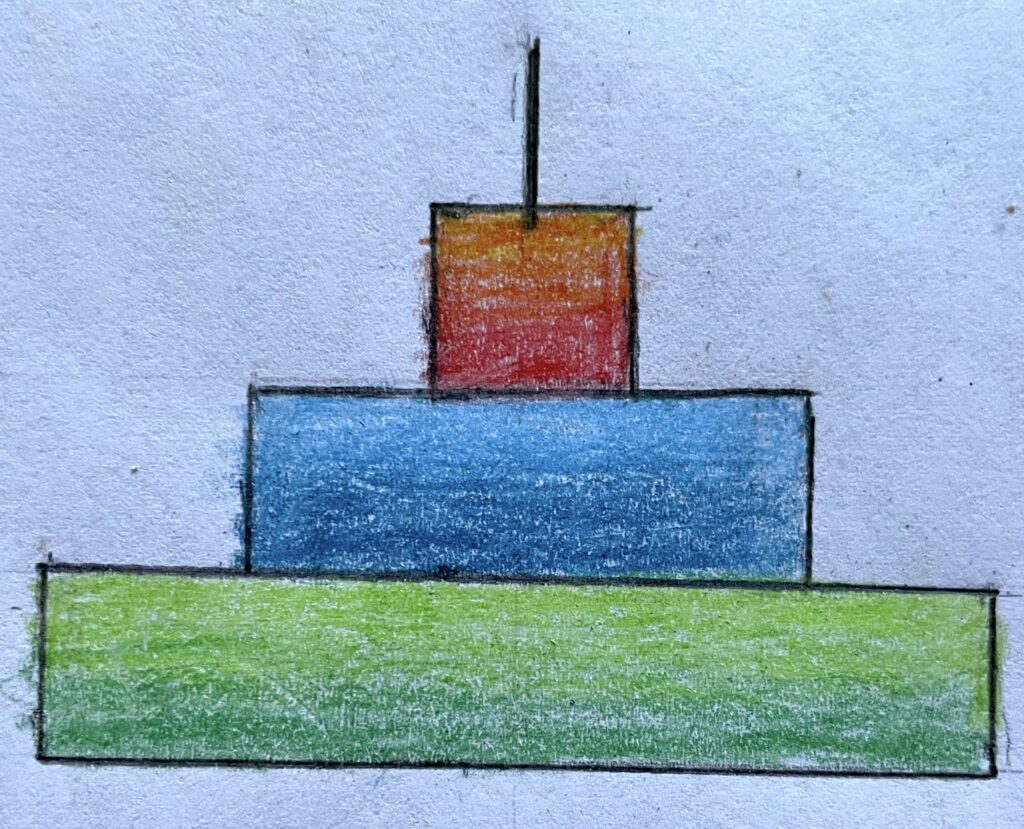

As many of us learned in high school biology, there is a food or energy pyramid ( a more accurate portrayal of the food chain model) in which all the producers are at the bottom, using the magic of photosynthesis to actually create stuff for the rest of the chlorophyll-lacking consumers to enjoy. Let’s be clear on this: no animal, including humans, is a net producer of food energy or soil fertility. We merely concentrate and move fertility around, destroying much of it in the process.

Therefore, if you choose to keep animals for food, labor, entertainment or whatever, then go for it, but don’t delude yourself that they are producing soil fertility: that ultimately comes from the plants they ate, minus the great amount that was lost or destroyed though their (and our) life processes.

Now back to the exception I mentioned earlier: grassland. There are certain regions of the world, like Patagonia, Kenya, Mongolia and Wyoming, where the climax community is grassland, not forest, even though forest would be more eco-efficient. All those regions share one feature: lack of water. Move that mountain range or shift that jet stream and they will begin to evolve toward forests. After all, trees have the advantage of height and a meters-deep canopy of horizontal leaves poised to maximize capture of solar energy. Their deep-delving root systems reach down beyond the biosphere — the land of the living — to dissolve and pump up minerals that were deposited by long-gone glaciers and volcanoes or other geological processes. Furthermore, grass dies back down to the ground every year and most of its biomass is tied up in relatively shallow sod. In other words, forests are nature’s best invention so far for soil-building; prairies are second best.

What implications does all this have for our farms and gardens? If we wish to farm as sustainably as possible, given that animal products are not a net source of fertility (nor of nutrition for that matter, but that’s another issue), what materials shall we use to not only maintain but actually build soil tilth? Obviously the products of the pasture — grass and all the associated broadleaf weeds — are an excellent source, especially if used without being put through an animal first. Unlike the dairy farmer who aspired to make hay from timothy and clover for finicky cattle, I’m delighted to have lots of goldenrod, buttercups, daisies, and even ferns in my mix (which is technically not hay as I don’t cure or bale it). The variety of plants is more nutrient-diverse than a pure grass-legume mix, and the earthworms, molds, bacteria, etc. that break it down are much less fussy than ruminants. I feed such plants to my crop soil either as mulch or compost.

Given that forest ecosystems are much more eco-efficient than grassland/pasture, then my woodlot is an even more obvious source of soil-building material. The key to using woodland materials — leaves and ramial wood — is in reducing them to smaller sizes, both for ease of application and to accelerate decomposition. With leaves it is less critical; whole leaves can be used though they’re nowhere near as good as shredded. If one has a shredder, that’s ideal. But lacking that, one can get fairly satisfactory results using a push lawnmower and turning a leaf pile repeatedly between passes to get a more thorough and uniform size. That’s fine for composting and adequate for mulch, but for mulch a more confetti-like texture is ideal, and hard to get without a shredder. (This texture is important with my intensive garden spacing: rows are only 8 to 12 inches apart.)

Ramial wood is more problematic as it really must be reduced to moderately fine chips, which requires a chipper/shredder. Even the chips which I often procure from the highway crews are a bit too coarse and variable for most of my uses and need to be re-chipped. This is extremely quick and easy in my Amerind-McKissick chipper/shredder. If I use ramial chips in my compost, I usually leave them in a heap for a year, often dumping buckets of urine on them. However, I usually apply chips as a groundcover in late fall and till them in shallowly in spring.

There seems to be an obvious connection between ecoefficiency and veganic (stock-free) farming and gardening. However, I don’t like just preaching to the choir, especially when the ideas could be utilized to advantage by others, so I want to emphasize that even if you’re not a vegan (as I am), and even if you keep livestock and have manure (as obviously you will), that certainly doesn’t mean you cannot apply the concept of ecoefficiency, whether instead of or in addition to your animal inputs. After all, I still use the only animal manure I have — my own composted humanure. (Read my previous article in The MOF&G, titled “Humanure: It’s Not a Four-Letter Word,” at mofga.org for more on that topic.) Either way, you will be more sustainable — more eco-efficient — than you are already, and will be utilizing materials like tree leaves and ramial chips which are otherwise going to waste. It is literally taking “organic” to new heights and depths.

About the author: Will Bonsall lives in Industry, Maine, where he directs Scatterseed Project, a seed-saving enterprise. He is the author of “Will Bonsall’s Essential Guide to Radical Self-Reliant Gardening” (Chelsea Green, 2015). And indeed, he is also a distant cousin of another exemplary Maine horticulturist: Tom Vigue. You can contact Will at [email protected].

This article was originally published in the fall 2022 issue of The Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener.