|

By Jean English

The story is the same, only the crop variety and country have been changed.

The story is one of small scale farmers who were producing primarily for local markets being told by foreign governments and multinational corporations that they have to change their ways: to monocultures; export crops; synthetic pesticide and fertilizer use; and, eventually, to genetically engineered (GE) crops.

In April, MOFGA’s El Salvador Sistering Committee, which links MOFGA with like-minded organizations in El Salvador, was visited by representatives from ENGAGE – Educational Network for Global and Grassroots Exchange – and from Thai activists whom ENGAGE brought to the United States. Those visitors included Mr. Bamrung Kayuta, a Jasmine rice farmer, leader in the Assembly of the poor people’s movement in Thailand, and the southeast representative for Via Campesina, the international peasants’ movement; Mr. Ubon Uwa, a regional representative from the Alternative Agriculture Network, working directly with Thai farmers to promote sustainable agriculture, reduce pesticide and chemical fertilizer use, and prevent exploitation of farmers by governments, corporations and trade regulations; and Ms. Chalida Maneepakorn, a Thai student organizer who is building student involvement in social issues.

Uwa told MOFGA that farmers in Thailand face many of the same issues as those in El Salvador. “Forty years ago, farmers in Thailand grew many kinds of things. Everyone had 7 to 9 acres. They grew for their family. Rice was the primary crop; they grew it once a year and used animals to plow the land.”

In 1961, the World Bank and the Thai government began building roads and dams and suggested that Thai farmers start producing food for export. “In the Northeast, people started cutting down the forest to grow corn and kenaf.” What was once 60% forested is now about 20% forested. The government also promoted use of new corn and rice varieties.

The Thai government has promoted chemical-intensive, export agriculture of such major crops as tapioca, sugar cane and corn for 40 years, Uwa continued. Borrowing to switch to this system has put Northeast Thai farmers into “huge debt – twice the average annual income.” To try to get out of debt, people move to the city, drive taxis, work in factories or clean houses. “Only old people and small children are left in the villages.”

The Green Revolution had further effects, Uwa explained. “Local varieties were lost; agriculture changed from providing for the family to export-driven; and relationships between people in villages changed. The culture of helping one another with work changed to having to hire people for money. People are just thinking of capital. This breaks up the family.”

To add to this insult, the quality of Thailand’s traditional Jasmine rice is being compromised. Chris Deren, a USDA-supported researcher at the University of Florida, is trying to breed the rice so that it can be grown in the United States and be machine harvested (see https://news.ufl.edu/2001/09/11/jasmine/ and www.indiatogether.org/agriculture/articles/noel_jasmine.htm). If Deren’s rice is patented, importing traditional Thai jasmine rice may become illegal, or the “improved” rice may be grown so cheaply in the United States that Thai rice could not compete. “The ideas concerning patenting rights were created here in the United States and create a lot of problems in the Third World, because they allow companies to steal genetic resources,” said Uwa.

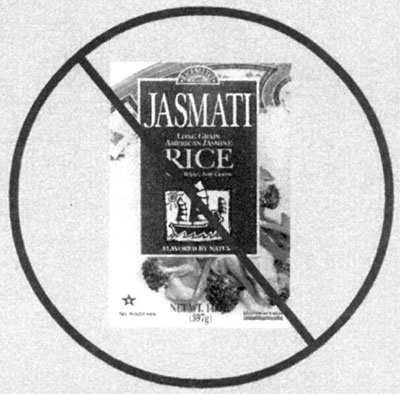

At the same time, a company called RiceTec/RiceSelect is using the reputation of Jasmine rice to mislead consumers into buying its “Jasmati” rice, which capitalizes on the popularity of Jasmine rice from Thailand and Basmati rice from India but contains neither, according to ENGAGE. “Jasmati” rice is actually a variety called Della, an American derivative of Italian Bertone rice. If consumers try “Jasmati” thinking it is Jasmine rice from Thailand and find that it does not taste good, they may stop buying Jasmine rice altogether, impacting Thai farmers. When Thais protested this situation, the Federal Trade Commission ruled in favor of RiceTec, saying that the name ‘Jasmine’ simply relates to a fragrant rice.

Rice farmer Bamrung Kayuta, who spoke out on such issues at the WTO talks in Seattle, says that he met small farmers from the U.S. there who had similar problems. He learned about solutions such as CSAs and Fair Trade products. “Third World countries export sugar cane, kenaf and tapioca, but they’re still hungry,” said Kayuta. The Jasmine Rice Campaign of ENGAGE has a program to export organic, Fair Trade Jasmine rice to Europe and hopes to extend that program.

|

Uwa said that the Alternative Agriculture Network that he works with is similar to MOFGA. It started 11 years ago, when the price of rice was very low and Thais noticed that those practicing integrated agriculture could survive such drops. The Network holds seminars, tries to influence government agricultural policies – even protesting at a government building for 99 days at one point – demanding an end to the use of chemicals in their country that are banned in the United States and Europe, and asking for money to support sustainable agriculture. The economic crisis in the area interfered with much progress, but the Network now has some government money for a pilot project on sustainable agriculture. At the same time, however, the Thai government wants its farmers to grow genetically engineered papaya, corn and soy. “Monsanto is giving letters to farmers now,” said Uwa, trying to get them interested in growing GE crops.

Uwa concluded with a plea for further MOFGA-Thai farmer exchanges. “We want a delegation of MOFGA farmers to go to Thailand!” The ENGAGE trip to the United States was sponsored by Oxfam America.

For more information about ENGAGE and The Jasmine Rice Campaign, please contact Laura Millay at PO Box 336, Surry ME 04684; (207) 266-8064; [email protected]; or visit https://engagetheworld.org/.