June 4, 2021

Three-Lined Potato Beetles

Three-lined potato beetles are typically a minor pest, but can cause real damage to small plantings of tomatillos or husk cherries. Read more about three-lined potato beetles here.

Leek Moth

Overwintered leek moths had an early first flight this year — about a month ago. That means the first generation of the year is expected to emerge from their cocoons soon. The eggs they lay will hatch out to the second generation caterpillars which typically cause more damage. The pest is still confined to only a few areas in the state (as far as we know … ) but it may be a good idea to make sure they haven’t spread to you, as now would be the critical time to prevent damage from the second generation. Read more about leek moth here.

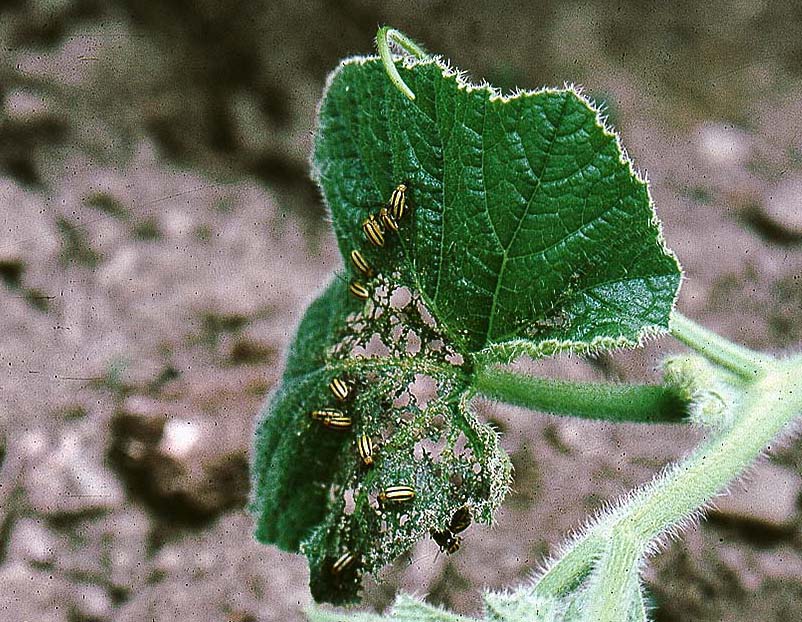

Striped Cucumber Beetle

Striped cucumber beetle is our most serious early-season pest in cucurbit crops. These beetles spend the winter in plant debris in field edges and with the onset of warm days and emergence of cucurbit crops they move rapidly into the field. Densities can be very high, especially in non-rotated fields or those close to last year’s cucurbit crops. Adult feeding on cotyledons and young leaves can cause stand reduction, delayed plant growth and reduced yield. Critically, the striped cucumber beetle also vectors Erwinia tracheiphila, the causal agent of bacterial wilt, and this can be much more damaging than direct feeding injury. Crop rotation, transplants and floating row cover are cultural controls that help reduce the impact of cucumber beetles. Many growers use row covers or exclusion netting on cucurbits for both growth benefit and insect protection, removing them when flowering begins to allow for pollination. Parthenocarpic varieties do not require pollination and can allow for delayed removal of row covers or netting.

Avoid early season infection with wilt. Cucurbit plants at the cotyledon and first one-to- two leaf stage are more susceptible to infection with bacterial wilt than older plants, and disease transmission is lower after about the four-leaf stage. Using row covers to keep the beetles out at this most vulnerable stage can be very effective.

Beetle numbers should be kept low, especially before the five-leaf stage. Scout frequently (at least twice per week before emergence, and for two weeks after crop emergence) and treat after beetles colonize the field. The threshold depends on the crop. To prevent bacterial wilt in highly susceptible crops such as cucumber, muskmelons, summer squash and zucchini, we recommend that beetles should not be allowed to exceed one beetle for every two plants. Less wilt-susceptible crops (butternut squash, most pumpkins) will tolerate one or two beetles per plant without yield losses. Spray within 24 hours after the threshold is reached.

Insecticides that are allowed in organic production (listed by OMRI, the Organic Materials Review Institute) include kaolin clay (Surround WP), pyrethrin (PyGanic Crop Spray 5.0 EC), and a mixture of pyrethrin and azadirachtin (Azera). Surround should be applied before beetles arrive because it acts as a repellent and protectant, not a contact poison. With direct-seeded crops, apply as soon as seedlings emerge if beetles are active. Transplants can be sprayed before setting out in the field.

Perimeter trap cropping with a preferred cucurbit crop (usually a Curbita maxima such as Blue Hubbard or Buttercup) can give excellent control with a dramatic reduction in pesticide use. For details on using perimeter trap cropping, see University of Connecticut Integrated Pest Management Program’s “Directions For Using a Perimeter Trap Crop Strategy to Protect Cucurbit Crops.”

(Modified from the UMass Vegetable Notes Newsletter, written by Ruth Hazzard and Andrew Cavanagh)

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, through the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program under subaward number ONE19-334.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.