|

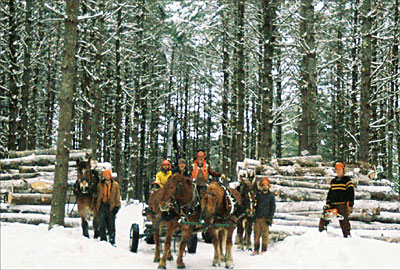

| The logging crew at MOFGA’s Common Ground Education Center, Feb. 2008. Photo by Nick Zanstra. |

by Pete Hagerty and Sam Brown

A Little History

“We had a lot of fun, made a pile of wood, and didn’t nobody get hurt. Now, pay attention because it gets complicated for a while before it gets plain.”

Jason Glick brought his horse Dan and his chainsaw from Appleton, and cutter Jim Ostergard also came from that little town. Nick Zandstra drove from Vermont with his saws and axes. John Cullen brought his saw from Topsham, as did Joel Tripp from Saco. Brad Johnson and his mare Sal (who live at Chewonki, on the coast), Pete Hagerty and his team of Nick and Willie from Porter, Pete Stratton and his mare Princess from Sidney, Jim Hawkes and his oxen Storm and Thunder of Albion, and Paul Birdsall of Penobscot, fresh from a hernia operation, set choker chains. “They said I could lift 20 pounds ok,” said Birdsall with a boyish grin. All these creatures (and more) collectively improved part of MOFGA’s Unity woodlot during five days in February. Andrew Marshall, the MOFGA staff and Sam Brown from Cambridge organized the cutting.

The pine stand through which many thousands of Common Ground fairgoers walk, from the large south parking lots to the Pine Gate, was abandoned from pasture in the 1930s and ‘40s and grew up all at once. After MOFGA purchased the property in 1997, Barrie Brusila prepared a forest management plan for the 100 or so acres of woodlands that accompany the fairgrounds. Over the last decade, MOFGA’s Low Impact Forestry (LIF) committee has taken on the responsibility of implementing Brusila’s recommendations for improving the woodland quality, but it never had enough time or energy to fully implement them – until the crew, mentioned above, assembled on February 6 for five intensive days of cutting and yarding over a small portion of the woodlot.

|

| Peter Hagerty with Willie and Nick. Photo by Jennifer Glick. |

The Plan

John, Nick, Joel and Jason (and sometimes Sam) spread out over about 3 acres as choppers, cutting marked trees for logs and pulpwood while maintaining clear trails where the draft animals could operate. Trail clearing required lots of brush management, which meant chopping brush small enough to move it by hand if necessary, providing the additional aesthetic benefit of smaller, lower brush piles.

The harvesting system had been planned ahead of time, but the actual methods used were fine tuned due to weather and as crew members got more comfortable with each other. Many had been working together for almost a decade and quickly established a natural rhythm.

The initial idea was to cut single trees and mark or cut them to length at the stump, and the animals would haul them to the woods road, where a truck could take them to market eventually. The ground was perfect: about 4 inches of a hard, crusty, solid snow base, not too deep or sharp to slow travel or cut hooves. Weather that was bringing record snows to towns south and west of us magically passed us by. Up in the pine branches, though, the same crusty ice and snow formed dense adhesions, which made felling much more difficult, especially during the first few hours and days when the forest canopy was still closed and dense. Initially, almost every tree had to be pulled down by a horse, which slowed production until large enough openings in the canopy allowed choppers to get trees on the ground unassisted.

|

| Brad Johnson with Sal. Photo by Jennifer Glick. |

The Challenge

Horses and oxen were replaced in Maine woods operations sometime after WWII, when heavy machinery arrived. Although horses have maintained a presence in logging, their numbers are a small cry from the day when all pulp and saw logs were hauled from the stump by four-legged animals. The LIF group began using horses and oxen at MOFGA’s woodlot because its members were passionate about these animals’ role in sustainable, responsible forestry management, but LIF was equally interested in integrating appropriate and more modern machinery with the animals when this made sense.

One challenge a teamster always faces when coming out of the woods with a hitch is how to pile this wood fast enough that it is readily accessible to the trucker. The obvious way – to pile it by hand in long, high rows – was an option back when the paper industry wanted pine pulp in 4-foot lengths, but for this cut, we were producing pulp in 8-foot lengths, with some sticks weighing over 300 pounds, and saw logs up to 16 feet long weighing over 500 pounds. The solution was to hook a log forwarder (a heavy-duty trailer with hydraulic log lifting boom) loaned by PenBay Tractor in Burnham to Andrew Marshall’s diesel tractor and tow it to various landings along the woods road to sort and pile logs and pulpwood.

Back in the woods, after the chopper felled a tree, a single horse or team arrived to hitch up the wood and haul it to the yard. The horses or oxen would arrive at the wood yard where they would unhitch their load next to Andrew’s rig. As they headed back into the woods, Andrew would expertly pick up, sort and pile the logs and pulp, leaving the wood yard clear for the next teamster.

|

| Jason and Dan pull a log from the woodlot. Photo by Jennifer Glick. |

We began operating with three yarding areas along the road but soon discovered that Andrew had to move too frequently and could not keep ahead of the flow, so yards began to get plugged up. So we consolidated the three yards into one, requiring the teams to cover a bit more distance and sometimes creating a small traffic jam – but giving everyone a little rest and time to check on each other.

Transferring information from forester to chopper to teamster in order to get the best value from each piece of tree and not damage any remaining trees was tricky, but a system developed. Sam, working in the wood yard, sent comments about log lengths and quality to the choppers via the teamsters, and eventually three good, consistent products piled up: pulpwood for paper, low grade saw logs for sale to a local mill, and high grade saw logs for MOFGA’s future buildings.

Draft animals, being living creatures, give feedback through body language about decisions the humans around them make. The LIF crew used this feedback numerous times to adjust travel routes (uphill or downhill), adjust load sizes, decide when to start and stop for the day and how much brush to clear from trails and when to just relax and smell the proverbial flowers.

The Social Part

Pete Hagerty parked his stock trailer nearby on the roadway. With a tiny woodstove inside, it served as a lunchtime shelter for the crew and a welcome concentration point for tools, repairs and supplies. MOFGA’s shop building provided a warm space for saw and harness maintenance at night.

Grub for the crew was a major draw, as MOFGA is famous for hearty meals of excellent food. Patti Hamilton, the LIF chef of recent years, cooked days’ worth of quality, high-carb meals in advance, and the resident loggers did the final preparations in the kitchen for breakfasts and suppers, with lunches warmed by dedicated MOFGA staff and lugged to Pete’s trailer. Loggers make great eaters and can do dishes like nobody’s business – even inheriting the remains of a vast banquet after a separate MOFGA event.

|

| The logging crew at the loader. Photo by Nick Zanstra. |

During evening meals on a long table hauled into the kitchen, we enjoyed reflection and humor. Those who did not fall asleep in their dessert were tucked in bed by eight in MOFGA’s warm and cozy farmhouse (vacant during this spell) with only the ripe smells of fellow loggers (and a few of their dogs) to cause concern. The draft animals bunked in the open barns. The only night that high winds, snow and low temperatures hit, the horses were stabled in the poultry barn, which has solid sides and a tight door.

Some of the logging crew volunteered, while others contracted with MOFGA on an hourly basis. Everyone had worked together before, sometimes for years, at the annual November LIF workshops, and that familiarity kept the operation flowing smoothly. Some members could work for only a day or two, others for the duration.

We harvested about 60 cords of pine products from the 3 acres. One-third was logs. About 10 cords per acre remain standing – trees of much higher quality than those we removed – and those trees will grow faster (having more crown space) and will be more valuable. We cut relatively heavily in order to encourage other species to grow in the newly opened areas, where MOFGA plans to plant desired species (red oak and maybe American chestnut, for instance).

The economics of the operation are in the accompanying table (please click on the link below). One unique factor that profoundly affected the profitability of the operation was that each crew member could bill for his services at the end of the harvest ($25/ hour plus $10 for each animal) or could volunteer his labor. Of 11 participants, five requested reimbursement (133.5 hours) and six volunteered (146.5) – suggesting that professional woodsmen can work well together profitably irrespective of personal finances. An overriding contributing factor was the great deal of time and energy put into preparing the event to ensure a safe, efficient and enjoyable environment. The bottom line included lots of smiles on people’s faces and an occasional whistle heard above the drone of saws. Plans are under way for another harvest this summer.

LIF February 2008 Logging Summary (Table of Expenses and Income)