Copyright 2006 by the author

When I first spotted it, I thought it was an unlikely place for an organic farmstand: still within Ellsworth city limits, right off a fast stretch of Route 1, across the street from a hotel and in a residential neighborhood. Pulling up, I assumed the Blackstone Gardens farmstand would be just another folding tray full of excess zucchini.

|

| Jay Barnes. Photo courtesy of Mary Blackstone. |

But the variety on the whiteboard was evidence of a real farm enterprise, and the lineup on the table was mouthwateringly impressive, including delicate lavender eggplants, batches of leafy herbs and heaps of ‘Cherokee’ tomatoes.

Salad greens were also advertised on the board, but I didn’t see any on the table. I assumed they were out, but asked the moustached man working in the garden.

“We pick it fresh for you,” he said matter-of-factly. “We don’t hold anything over.”

I ordered as much as he could pick, then roamed the spacious, 1-acre back yard filled with raised beds of beautiful flowers and vegetables. Soon, the man handed me two heaping bags filled with every type of green imaginable.

As he totaled my haul, I prepared for sticker shock, but the figure he gave me didn’t seem right. If it were, I would have been paying less for fresh organic goodies than for conventional vegetables at the supermarket. I tried to reason with him. He made me pay less.

I left with my bags, mourning that the stand was probably a one-shot harvest operation. No one could keep up this kind of quantity in an acre lot.

I returned every week for more, well into the fall

A Remnant Farm

Co-owned and operated by Mary Blackstone and Jay Barnes (the moustached man), Blackstone Gardens is a remnant from Ellsworth’s agricultural past. At the beginning of the 20th century, the property was part of a large dairy farm; the house and gardens were once an apple orchard. Hotels and houses now crowd together where the farm once stood, and a busy street cuts the land in two.

“This whole street was little more than a cowpath,” says Blackstone.

Her mother, Hazel, grew up next to the farm and rode around on the dairy’s milk-wagon as a child. When Hazel married Albert Blackstone, they bought a corner of the farm and built the little white house that stands there now.

One of the first things the Blackstones did when they moved in was plant their first raised bed, an asparagus bed. They harvested the first asparagus five years later to celebrate the birth of the their daughter, Mary.

“I sort of date my life according to the things planted around the house,” Blackstone says.

The bed is still in use.

Blackstone grew up helping her mother in the garden. Eventually, she moved to Canada, where she now works at a screenplay-development center at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan. During breaks and in the summer, Blackstone came home to help her mother in the garden.

|

| The Blackstone home in Ellsworth. Photo courtesy of Mary Blackstone. |

Just a Half-Day a Week

Hazel kept the garden going successfully after her husband’s death, always having surplus vegetables and flowers to give away or barter. She also worked at the Ellsworth Library–where she met Jay Barnes. Every time Barnes came in for a book, Hazel tried to convince him to work for her at the Gardens.

Barnes was no stranger to gardening. “That’s what I always did. I grew vegetables,” he notes.

Farming is a family tradition for Barnes. His father farmed 3,000 acres in Aroostook County before buying a farm in Lamoine, where the Barnes family farmed land that had been in continuous production since 1880. But when his father used chemical fertilizers and pesticides on the land, the soil quickly collapsed.

“There weren’t any earthworms or anything,” Barnes laments.

After seeing neighbors succeed with organic gardening, Barnes’ mother was convinced it was the way to go, but his father was not–so the two divided a garden plot and had a friendly competition. His mother’s organic plot trounced the conventional one, and the family farm converted. To build the soil, Jay Barnes used crop rotations, cover crops, seaweed and horse manure.

“All the earthworms came back,” says Barnes.

Barnes finally surrendered to Hazel Blackstone’s entreaties 15 years ago and agreed to help at the gardens. Originally, he was to work a half-day a week. Then it became a day, then three.

A Great Location for a Farmstand

Mary Blackstone came to spend more time at home since her mother’s diagnosis with Alzheimer’s in 1995, carrying on the garden when Hazel was no longer able. The gardens were not organic until the mid-nineties. Barnes said the change happened overnight.

“Mary took a master gardening course,” explains Barnes. “Once she did, that was the end of commercial fertilizer.”

The garden prospered with the switch. Blackstone carried on the bartering tradition and sold some produce to a local restaurant. Yet despite the greater surplus each year, the farmstand idea didn’t take hold until a couple of years ago.

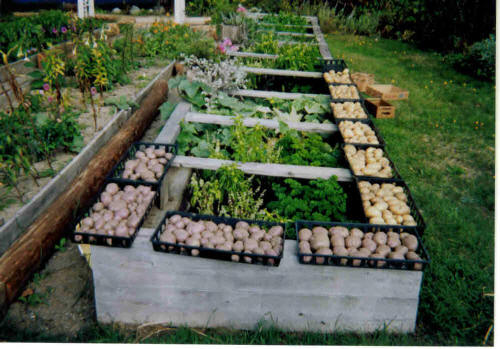

|

| Sweet basil grows in coldframes, newly harvested potatoes. Photo courtesy of Mary Blackstone. |

It was Barnes’ idea. He’d had some success with a farmstand in Lamoine, “but there wasn’t much volume,” he explains. He saw that Blackstone Gardens had a much better location and suggested a stand to Blackstone. She was cool to the idea at first, but “he kept needling away,” she said. Eventually Blackstone gave in and she’s happy she did. While she could always find a home for her vegetables, she no longer has to worry about distribution; her customers come right to her door. The social aspects of having a farmstand have been fun, too. “I met my neighbors,” she says. “I kind of enjoy the contact.”

She also enjoys watching people get in touch with their food while they wait for her to pick it. “It grows like that, does it?” is the most frequently asked question. “This way, I think the stand makes more of an in impact,” she says.

The Ins and Outs of Urban Gardening

The vegetable choice at Blackstone gardens comes down to taste. “To be honest, my attitude was to grow things I liked and I could use,” Blackstone admits.

Everything is grown in raised beds, which helps extend the growing season and prevent problems with flooding and slugs. To further extend the season, Jay starts longer-growing crops, such as tomatoes and eggplant, indoors with 16 growing lights. When the crops are transplanted into the ground, they’re shielded from frost and pests with plastic IRT (infrared transmissible) mulch.

Barnes and Blackstone enrich the soil with seaweed that Barnes trucks himself from Lamoine, compost (made with seafood waste from Gouldsboro) and crop rotation. In the fall, they plant winter rye to prevent nutrients from leaching.

Many of the crops grown at Blackstone Gardens are trellised, including such wide-spreaders as cucumbers. This maximizes space and minimizes pest damage, but also helps save on wear and tear for the gardeners. “I’m not as young as I used to be,” Blackstone explains. Larger spreading crops such as squash are grown at Jay’s farm in Lamoine. The gardeners also sell a multitude of herb seedlings and flowers.

Despite gardening in city limits, Barnes and Blackstone still have to protect their produce from animals. Mesh fencing on tall poles holds deer off, at least until rutting season. “A buck will go right through it,” Barnes observes. The fencing also protects the garden from rambunctious children; when the fencing went up, vandalism vanished.

A Gardening Partnership

Hazel Blackstone passed away last fall. Her daughter plans to continue the gardens despite splitting time between Saskatchewan and Maine, since she enjoys the balance between academic and organic. “[Gardening] is a nice antidote to the politics of the university environment,” she says—although she looks forward to retiring in Maine and devoting herself to the gardens full time.

Despite the scarcity of room for expansion, Blackstone hopes to plant at least a couple of apple trees to restore the orchard symbolically, and customers will find more produce at the stand this year, as Barnes plans to devote more Lamoine farmland for farmstand veggies. The business partners have also undertaken a new project this year: They’re co-presidents of the Ellsworth Garden Club. Blackstone says the stress of running a garden together is one thing, but laughs and says, “That’s nothing compared to managing a garden club.”

Craig Idlebrook is a freelance writer who worships his baby daughter, especially when she takes a nap. He can be reached at [email protected].