|

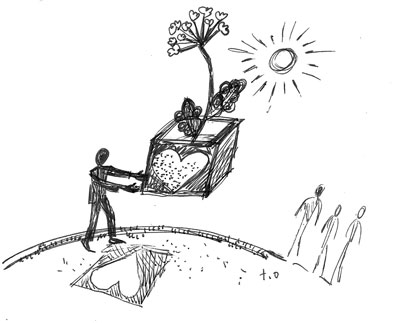

| Toki Oshima illustration |

By Grace Oedel

A celebration of abundance took place at the annual Seed Swap and Scion Exchange held at MOFGA in March. People arrived with bundles of scionwood neatly labeled or jars of seeds rattling cheerfully. Toddlers helped thresh beans by jumping on dry shells; musicians fiddled as dancers swung around baskets of hazelnuts; teachers offered expert knowledge about grafting, orcharding, permaculture and seed saving to packed rooms of eager students. We extended the invitation for people to share anything that generates more of itself – such as kombucha, sourdough starter, compost starter – and the table overflowed.

Because participants did not have to pay to attend the event, and because people offered all the seed, scions and treats free, the swap feel particularly joyful. Plant material itself offers an incredible example of how the principle of abundance can function. While caring for and pruning your trees, you generate scionwood to share. Abundance generates more abundance.

This experience of biological profusion is the opposite of a material scarcity mindset, in which the fear of losing resources makes us hoard and guard rather than share openly.

The feeling of community-supported abundance reminded me of the Jewish commandment for tzedakah. This word is commonly mistranslated in English as ‘charity.’ In Hebrew, tzedakah literally means justice or righteousness. Doing tzedakah, then, is not something that makes you an exceptional, magnanimous person. You do tzedakah to fulfill a basic piece of your duty as a human; you do tzedakah because it is required for a fair world.

According to halakha (Jewish law), everyone should contribute 10 percent of what he or she makes. This requirement most commonly applies to money (many observant Jewish people donate 10 percent of their salary, for example), but I wonder: What if everyone shared 10 percent of everything? If every gardener shared 10 percent of the food she grew? Ten percent of his seeds? Of her compost? Perhaps what felt so delightful about the Seed Swap and Scion Exchange was a sense that a fair, just world was being imagined and inhabited. People offered what they had to share and left with more than they could imagine.

Perhaps tzedakah also offers a partial solution to the question of shmita, the biblical agricultural sabbatical year, which I wrote about in the last MOF&G. How can farmers possibly take off every seventh year to let themselves, and the land, rest? With tzedakah, just as a need exists for people to offer gifts, so does a reciprocal need for someone to receive them. Accepting a gift of tzedakah, then, is not something to be looked down on or shamed, but rather celebrated as a healthy sign of a functioning world. We can then all step into both roles – giving and receiving. Perhaps for six years the farmer could contribute to such a system (say, for example, sharing revenue from CSA shares) and during the seventh year the farmer could draw from it. The Seed Swap and Scion Exchange offered me a taste of a tzedakah-driven food system, a resilient culture in which we all have enough.

About the author: Grace Oedel is MOFGA’s educational events coordinator. She obtained her B.A. at Yale University where she studied ecological theology. She has been involved in agriculture and social justice since her college years.