|

| Fava beans, from Thomé, Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz, 1885. English photo. |

By Will Bonsall

So many names for one species: favas, broad beans, field beans, Windsor beans, horsebeans, tickbeans, bell beans, pigeon beans, etc.! And such a long history: Along with wheat and barley, favas have been cultivated by humankind since the dawn of agriculture. Caves in Iraq have yielded fava remains more than 5,000 years old.

Actually, favas are not “true” beans at all; Vicia faba is really a giant-seeded vetch. Nevertheless, before Europeans discovered America, favas were synonymous with “beans” in the Old World. They certainly are widely grown today: From Britain to North Africa, from Latin America to the Baltic to Southeast Asia, different cultures find different ways to use the hardy legumes. Indeed, it has always seemed to me that favas are an important crop nearly everywhere EXCEPT the United States, and I never understood why not here as well.

Although favas occur in an amazing range of sizes, shapes, colors and uses, they basically fall into one of two types, or races: majors or minors. The latter are generally the size and shape of a small peanut, while the former are more like a large lima bean with a swollen end.

I first encountered favas as a teenager, a holiday gift from a Lebanese family friend. My mom and I simply boiled them awhile without soaking. They remained tough and quite forgettable – indeed, I forgot all about them for several years. When I next met up with fava beans, they were from India and properly cooked. I liked them a lot better.

Culture: Cool Conditions

From their origins, I assumed favas must require a long, hot season to mature. How little did I know! Favas are also grown in many cool, short-season regions, such as Scandinavia, and when they are grown in more arid countries, it is as a winter crop, their idea of winter being relatively cool and rainy.

|

| Fava bean plants, their flowers and pods growing at the garden of Primo Restaurant in Rockland. English photos. |

|

|

Favas are actually a rather quick-maturing crop, sometimes earlier than peas. I’ve read that favas require a long (three- or four-month), cool season. That is certainly not my experience in Maine, where I’m often eating green shell favas by the Fourth of July. They not only can tolerate lots of cold, they MUST have cool, moist weather to perform well.

In the western Maine mountains, I must get them in very early (before May 10); otherwise, when the weather turns hot and dry, the plants will be at the stage where they’re most vulnerable to the fungal disease called chocolate spot and to aphids. Of course soap spray can help deter the latter, but tardy blossoms may abort before setting pods. For this reason, later sowings will almost always fail, even though there may be plenty of TIME to make a crop.

However, I have discovered a trick for getting a later crop with comparatively little disease (in the case of green shell as opposed to dry beans). As soon as the main picking is done and the stalks begin to languish, I clip off all the senescent (old) growth and compost it. Most of the root crowns will be making a second flush of new stalks, which I’m careful not to damage. With any luck, these new sprouts will not flower until temperatures have dropped enough so that they will not abort, and the pest and disease issues should be less pressing then. I may give them a second mulch of coarse compost and a heavy watering. For some reason this is much more successful than simply sowing later; it gives a small, late crop at a time when I would otherwise get none at all, plus the plot is well fertilized for whatever crop may follow.

Young fava seedlings are dearly beloved of cutworms, but I find that makes them very useful as a trap crop. Since I space them 5 to 7 inches apart, it is easy to spot a plant that has been toppled recently, and to dig around there and destroy the culprit. Daily patrols during the first couple of weeks after emergence give me complete control over the pest for the entire season, unlike peas, which are sown too thickly to spot individual incursions until it’s too late.

Another pest of favas is the leafhopper. This is a broad-range nuisance on beans, potatoes and much else, but its taxonomic name, Empoasca fabae, should perhaps tell us something. The severity of infestation varies greatly from season to season, as the insects are carried in from the South by jet streams, which don’t always loop this far north. When leafhoppers do threaten to infest, garlic barrier can effectively deter them if you act quickly. Left to their own, the tiny pests will chew on surfaces so you won’t notice them at first, until the plants develop an overall faded, grey-green look and pod production drops.

Under ideal conditions (plenty of humus and ample moisture), I’ve had fava stalks reach 6 feet high. “They” say you don’t need to support them unless it’s windy, but I nearly always run strings and sticks down the rows to keep the stalks from breaking over, and that’s when I’m planting them in wide (4-1/2-foot) beds with three adjacent rows.

By the way, fava blossoms can be quite attractive, white pea-like flowers with a black spot near the base. There are also magenta flowered varieties, but they’re rare.

Cooking with Favas

How does one use favas? Let me count the ways. Home gardeners usually prepare them as green shell, i.e., when the beans have fully filled out but are still green and succulent (like table peas). For this, the “major” types are preferred, if only for the ease of shelling them out. An elderly gardener friend compared the flavor to “peas which were gone by.” I call that flavor “hearty” or “robust,” but not everyone goes for it, just as folks tend to love or despise broccoli or parsnips.

Favas lend themselves very well to Italian cuisine, especially pasta-tomato dishes. A favorite dish of ours, which we call “summer stew,” combines green shell favas with tomatoes, peppers, onions, garlic, zucchini and romano beans, served over freshly baked whole wheat bread. I also love them plain with steamed or roasted root-crops.

And green shell is only the beginning. The “minor” types are especially good as a dry bean, presoaked and boiled like pintos or navy beans. They’re often sold like that, salted and canned, in Near Eastern grocery stores.

The dry beans, whether major or minor, can also be ground into flour in a grain mill and used to replace soy in veggie burgers, or to replace chickpea flour in falafel. I’ve read that fava flour is also used as a “conditioner” in traditional French bread, and we have used it that way with success.

|

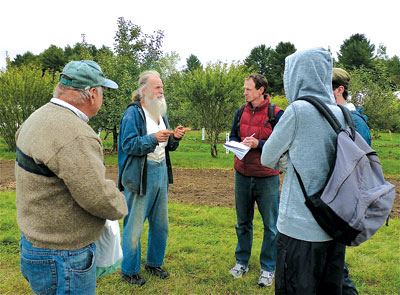

| Will Bonsall (center left) talking with Common Ground Country Fair attendees. English photo. |

My Peruvian sister-in-law tells of a way of preparing “abas tostadas,” which are somehow fried in a clay pot until they puff up, sort of like popcorn. I’ve never figured out how to do it right.

Some people recommend eating the immature green pods, much like green beans or snap peas. I’ve tried them and found the taste and texture to be distinctive and not unpleasant, but I greatly prefer the filled-out bean seeds.

Favas are not grown exclusively for human food; they’re also raised for stock feed, especially in cool regions where soy doesn’t mature well, such as western Canada and northern Europe. [Treble Ridge Farm in Whitefield, Maine, is trialing the crop to feed to pigs; see the feature story in this MOF&G.] I also read that they can be used instead of soy to make tempeh and miso, presumably using the same cultures.

Favas are full of easily digestible protein. They also contain high levels of L-dopamine, a substance used to treat Parkinson’s disease; plus they’re rich in omega-3 oils, which are heart strengthening and anti-inflammatory.

As healthy as favas are for most of us, they aren’t for everyone. For a very small percent of people of certain ethnicities (including Greeks and several other Mediterranean groups as well as some southeast Asians and Africans), favas and even the pollen of favas can act as a neurotoxin, causing a condition known as “favism” – an abnormal breakdown of red blood cells – which is thrice as common in men as in women. Although in those rare individuals it causes cumulative and irreversible damage, in others it confers a resistance to malaria by reducing the oxygen absorption of red blood cells. People who react badly to eating favas (fatigue, vomiting, etc.) should quit eating them and check with their doctor; the rest of us should just continue to enjoy them. I find it interesting that populations with the gene for favism are some of the very longest, heaviest users of favas.

Feeding Soils, Too

Favas are also used as a soiling crop, or green manure, due to their ability to produce lots of quick, lush, leguminous growth in the cold, early season. Indeed they are unusually efficient as a nitrogen fixer and yield lots of biomass in proportion to what they themselves require. The smaller seeded minor types are preferred for this because they are, well, smaller seeded, so it takes fewer pounds to sow an acre.

I have some tiny-seeded, purple-black varieties from Finland and Poland (not currently available for distribution). I find these distasteful for food, but that’s not what they’re meant for. The purple pigment is either tannin or anthocyanin, either of which acts like cellular antifreeze, enabling the seed to germinate in colder soil. (The same applies for purple-skinned field peas.) If the pests mentioned earlier are not serious problems, a mixture of favas with field peas, hay oats and barley is a particularly strong soil humus builder.

Finding Seed

The main type of fava offered by seed companies is Windsor, which is not a variety at all, but rather a generic name for large-seeded, green shell favas. There are many varieties of the type, but they all have light-green to buff seed coats. Some people prefer to peel the green shell favas before cooking, but I consider that about as sensible as peeling table peas or lima beans. I enjoy the texture of the skins (I don’t have a particularly macho digestion, but neither am I a complete wimp), which also contain a lot of the rich flavor and nutrients. Anyway, you do as you’ve a mind to; I have no opinion on the matter.

As curator of the Seed Savers Exchange fava collection, I’m responsible for maintaining more than 250 varieties, of several types, from all over the world. It is truly exciting to see the enormous variation in seed alone: giant, flat, thumb shapes and small, peanut-like seeds; seed coats of olive, buff, brown, bright red, lemon yellow, dark maroon, purple-black, bright green, violet; some seeds with purple speckles, red cheeks or brown spirals.

Unfortunately, most of the collection is not currently available for distribution until I can regenerate the aging samples, but commercial seed suppliers offer a good selection. You can locate suppliers in the Garden Seed Inventory, available from Seed Savers Exchange, 3094 North Winn Rd., Decorah, IA 52101, or at www.seedsavers.org).

About the author: Will Bonsall lives in Industry, Maine, where he directs Scatterseed Project, a seed saving enterprise. His extensive, bountiful and beautiful gardens are open for tours two days each summer. Dates are listed in the “Daytripping” feature in the June-August MOF&G. He is also a favorite speaker at the Common Ground Country Fair, and author of Through the Eyes of a Stranger, Yaro Tales Book One, available from Bonsall at 39 Bailey Rd., Industry, ME 04938.