|

| Sunflower seed is planted in rows 30″ apart using a tractor-mounted corn planter and cultivated several times with mid-mounted sweeps. These plants were growing at UMaine’s Rogers Farm. Rick Kersbergen photo. |

by Polly Shyka

If the pinecone is Maine’s state flower, then the sunflower, a native, useful, generous and beautiful plant, should be the national flower. Much to my chagrin, in 1986 President Ronald Reagan proclaimed the rose to be the national flower.

Earliest traces of sunflowers date from 3,000 BCE in the American Southwest. According to the National Sunflower Association, they were revered and used by Native Americans as a food source, medicine, dye and fiber plant and building material. Following Spanish exploration of the Americas, the sunflower began its global tour. Mere ornamental curiosities for centuries in Europe, plant variety selection began with Russian farmers in the early 19th century – for oil content, seed size and flavor. In 1880, U.S. seed catalogs began offering ‘Russian Mammoth’ sunflowers to American gardeners. Not until Canadian farmers had been growing sunflowers on thousands of acres did Midwestern farmers take an interest in this “new” oilseed. The first hybrid was bred in the 1970s, and since then much research has gone into sunflower breeding. In 2007, 1.7 million acres of U.S. soil grew sunflowers.

My high regard for sunflowers led me on a goose chase this past year. At a conference on grain growing in January 2008, I overheard several dairy farmers talking about “Henry’s press.” Being curious, I followed up with Henry – Henry Perkins, that is – who lives in Albion. Sure enough, he had purchased an oil press, or “extruder,” and was gearing up to grow soybeans and sunflowers in 2008 so that he could press oil from them.

What would a dairy farmer want with sunflower oil? Fuel independence AND a lower grain bill. Vegetable oils can fuel diesel engines, and what is commonly called the by-product from pressing oil, a high protein meal that can be fed to livestock, is more accurately a co-product on Perkins’ farm. In fact, he considers the oil the by-product and the meal as the sought-after substance. Oilseeds now join various grains as annually planted crops for this sustainability-minded farmer. As dairy farmers everywhere try to lower their costs of fuel and purchased protein, growing both of these inputs becomes interesting to the more pioneering types.

|

| Sunflowers coming into bloom at Perkins’ Bull Ridge Farm in Albion, Maine. Rick Kersbergen photo. |

On-Farm Learning

Perkins is an award-winning organic dairy farmer, current president of the Northeast Organic Dairy Producers Association, an agricultural pioneer and a great storyteller. People belly-laugh and cringe simultaneously as he describes farmyard fiascos. His often self-deprecating tales are entertaining, but they also chronicle a farmer’s “mistakes” and his willingness to help others learn from his mishaps. “Don’t let this happen to you” could preface many of his stories. His experiments with dozens of varieties of grains and oilseeds over the past decade, often under SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education) grants or otherwise partnered with university faculty, have informed many New England researchers as well as farmers.

Perkins grew his first few acres of sunflowers in 2007. “Just a few acres, planted with a grain drill. I sent my son out to mow the adjacent field, and he came back with bad news. He had mowed the sunflowers. They grew back, and even though I didn’t cultivate them, I did combine them and got enough seed to press.” As expected, the sunflower seeds came out of the combine with a full crop of weed seeds. Perkins did run the harvest through his seed cleaner, but his oil pressing did not go well. “Nobody told me that the seeds had to be warm. I pressed them in the cold and got next to nothing. Then I warmed them and the press, and the meal was nice. Hard to believe that I bought a bigger press based on this outcome. But I did. I don’t like to give up.”

|

| Henry Perkins transfers meal from the mixer wagon on the right to the hammermill on the left. The hammermill pulverizes the meal and mixes it with kelp and minerals. This powder is then mixed with silage and fed to the dairy herd. Polly Shyka photo. |

Sunflower Culture

Equipped with a larger model oil extruder, purchased from the same Swedish company, Täby Pressen, as his first, Perkins readied himself for another year of growing and processing oilseeds. In early 2008, he sourced organic ‘Defender’ sunflower seed from a farm in North Dakota. “A one-time-only deal,” he was told; due to a crop failure, the seed he got was “the only they had. But then… it wasn’t really a deal for me, since I had to put so much money up front for three or four years worth of seed.” Nonetheless, he purchased the seed and planted 35 acres in early and late May with a corn planter set for 30-inch rows. He adjusted the planter to drop 22,000 and 40,000 seeds per acre in different plots. The higher populations resulted in smaller heads, which seemed to dry faster than larger heads. Fewer weeds grew in the rows, as well. The planter placed the seed 2 inches deep in soil that was at least 50 degrees F. Sunflower seedlings can take temperatures as low as 24, so late season frosts are not a concern, according to Dr. Heather Darby of UVM Extension.

Perkins cultivated the sunflower acreage several times with mid-mount sweeps as he does his organic corn plantings. Regarding cultivation, “Timing is everything,” he says. “I know what to do, and if I can get to it, I’ll do it. And it DOES make a difference.”

|

|

| The Täby Pressen Model 70 two-phase extruder is mounted on a counter. The white tube from above feeds the extruder hopper from a bin on the floor above, and the motor on the right powers the screw press. Two grades of oil drip into separate trays, which direct the oils into separate 15-gallon tanks, while meal exits the extruder on the left and falls into a funnel over a hole in the floor, which leads to a mixer wagon parked in the basement. Polly Shyka photos. |

Sunflowers are not such heavy feeders as corn and soybeans, and his were well fed from the abundant organic matter available in Perkins’ manured and cover cropped fields. They require 100 pounds of available nitrogen per acre and a pH of 6.5 to 7.5.

Rick Kersbergen, Waldo County Cooperative Extension Educator and Dairy Specialist, says, “Sunflowers are actually a lot more tolerant of weed pressure than corn. We are seeing this in the trials, as well as the importance of rotating land out of sunflowers.” Sunflowers are notoriously prone to a white mold. Kersbergen says, “White mold is the common name for the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, which infects over 350 species of plants. It occurs commonly in Maine on crops such as beans, peppers, head lettuce and cucurbits to name a few, but there are few vegetables it will not attack. This fungus can cause extensive losses in the field and can continue to cause extensive post-harvest losses by rotting the fruit.” For these reasons, Kersbergen urges any farmers growing sunflowers to plant them in the same field no more than two years in a row or, better, in a new field each year. Rotations with grains, hay crops and corn can break the life cycle of the mold, but soybeans should not be planted after sunflowers – an important point for any dairy farmer who is also experimenting with soybeans for meal and oil, as Perkins is.

Perkins calls “tourists and neighbors” the biggest threats to his 35 acres of sunflowers. “They are pretty enough,” he admits, but this dairy farmer is motivated by the seed, fat with potential. The fields are beautiful: that gold color; the order of the rows; the way the plants track the sun across the sky. Sunflowers bloom along with Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, milkweed, ragweed and corn – all encouraging the low rumble of thousands of bees, flying to and from their multicolored hives at the edge of Perkins’ field. True to Perkins’ observation, though, I notice dozens, possibly hundreds, of “stumps” where flowers were cut. “My sunflowers must be all over town,” Perkins grumbles.

Harvesting and Drying

Perkins combined his sunflower seeds from the fields in October. He ran them through a grain dryer to get the moisture level down to 10%, necessary for long-term storage. Kersbergen says the heads must be “really dry or really frozen” to run through the combine well. At a sunflower trial north of Bangor, Kersbergen and the farmers had to wait until the night temperature had dipped below 20 before combining. “If the heads get rained on when they are dry and ready to be combined, the rain sits in the dimple on the back side of the flower, and the head acts as a sponge,” Kersbergen explained. “If there is not an adequate drying opportunity, they have to be frozen solid to be combined. You want the heads to basically shatter.”

Newer combines with feed tables or reels in front of the choppers are more efficient and less troublesome for combining sunflowers. Perkins was able to raise the combine just high enough – about 6 feet off the ground – to get most of the heads and as little stalk as possible. From the hopper on the combine, harvested seeds were augered into a grain bin adjacent to a small building near the farmhouse. They sat in this metal bin all fall, while Perkins completed other harvests and set up “Henry’s press.”

|

| Pencil-thick and steaming, soybean meal exits the extruder. Sunflower meal is almost black in color. Rick Kersbergen photo. |

Pressing

When I stopped to see Perkins’ tabletop-mounted oil extruder in action one January day, I realized, from seeing the skid steer, combine, several tractors and lots of other pieces of machinery and parts in the equipment barn, that Perkins is not only curious and willing to take risks, but he is also not intimidated by (and may even enjoy) running, adjusting and fixing another piece of equipment.

As I approached the door of the peaked building built into a hillside, with its two adjacent grain bins, I smelled a delicious, nutty aroma and heard the dull murmur of a machine running. Inside the spare building, the untended extruder, sitting beneath a drop lamp, was producing two nonstop streams of material. As it extrudes oil from the seeds, the Täby Press uses a large screw chamber to put the raw, unhulled seeds under high pressure. The high fiber and high protein (28%) meal, which is the diameter of a pencil and almost black in color, shoots out the far end with some force. This type of press was once described to me as “a continuous-flow pressure cooker.” In 20 to 30 seconds, the seed or grain goes from ambient temperature to over 300 F just from the mechanical energy that shears the material in a pressurized vessel. The extruder also “cooks” the grain so that proteins are more digestible for animals and humans. The heat deactivates anti-nutritional properties that occur naturally in soybeans and some other grains and pulses.

Perkins heats this three-story building all winter with soybean and sunflower oil using a Cleanburn waste oil heater, the type used in many mechanics’ garages. On the lowest level, two garage doors allow Perkins to bring equipment fueled with the raw, farm-produced oil into a heated space – a necessity, since vegetable oils congeal at low temperatures. “I am just experimenting with one skid steer, and it’s not running a lot this winter. I have to mix the vegetable oils with diesel in the winter, but in the summer I run 100% vegetable oil.” The soybean and sunflower harvests of 2008 should produce more than enough oil to run all his equipment for the warm months of 2009.

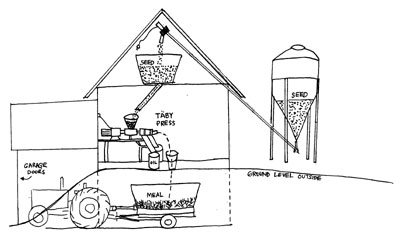

Grain bins outside the building feed an auger tube that goes through the building walls just under the eaves. The seed is augered up to the peaked ceiling of a small loft and then drops into a tube that leads to a 4- x 4-foot plywood bin with pitched sides and a hole in the bottom. This bin sits directly above the extruder on the ground floor below. The hole in the loft floor pipes seed into a hopper on the extruder. The flow is regulated by a valve but also is limited by the rate at which the extruder takes in seed. Gravity moves the meal through a large funnel over a hole in the ground floor and into a mixer wagon parked in the basement.

|

| Combined and cleaned seeds are stored in a metal bin outdoors. Seeds are augered from this bin into a wooden bin inside the loft. The seed then feeds into a hopper on the extruder, which is mounted on a counter on the main floor. The extruder crushes the seed and presses out oil, which drips into 15-gallon tanks. Meal falls into a large funnel leading to a hole in the floor and then drops into a mixer wagon (Total Mixed Ration wagon) parked in the basement. Illustration by Polly Shyka. |

Perkins’ Model 70 Täby Pressen can process 88 to 132 pounds of seed into 2.6 to 4.2 gallons of oil per hour, depending on the condition and type of seed. The oil exits the two-phase press at two places: Oil dripping out closest to the pressure chamber is a muddy brown-gold; the second exit yields clear, bright yellow sunflower oil. The two oil streams drip into separate trays and are filtered and used differently. Ideally, the golden oil would be bottled and sold for human consumption, and the less clean oil would be used as fuel on the farm. To market oil for human consumption, Perkins would need a processor’s license, and the cost of that plus visits from “another inspector” make the goal unappealing for now. So he runs the extruder as he needs meal for the organic dairy herd and stores the oil in old stainless milk tanks in the basement of the processing building.

Asked if he was pleased with his second Täby Pressen extruder (his first is for sale, by the way), he says flatly, “No.” But other extruders on the market that would move him toward fuel and protein independence are no better, he thinks. “I could choose from a Chinese, Indian or Swedish press. I have a hard enough time reading the Täby Web site. Plus the fact that the Chinese and Indian extruders are great big things made of cast iron and yet they are cheaper than my ‘little’ press, which can process more than I need in a year.” He adds, “Poor quality is remembered long after price is forgotten.”

Perkins will produce all the annual meal needed for his dairy herd from his sunflower and soybean harvests of 2008. If high protein meal is one of the fuels for making milk, he has achieved one type of fuel independence. Even if he is still buying petroleum diesel for winter fuel for his machinery, his experimentation has borne fruit. Perkins, true to form, recalls many days when he walked away from the press with shoulders slumped. “I’m learning each time I press. I try to figure out what I am doing wrong, then I tweak things and I try again. I can make pretty good stuff now.” If Perkins prefaces his stories with “Don’t let this happen to you,” surely his ending words must be, “It will be better next time.”

Resources

Täby Pressen www.oilpress.com

Henry Perkins can be contacted at [email protected]

About the author: Polly Shyka lives and farms at Village Farm in Freedom, Maine. She and her husband, Prentice Grassi, grow vegetables for local families in a CSA and for wholesale accounts. They also raise trees and shrubs, as well as pastured livestock. Polly can be contacted at [email protected].