|

| Anne and Eric Nordell have perfected a system of cover cropping and crop rotations that virtually eliminates weeds. In addition to the video and collection of articles noted at the end of this article, the Nordells are putting together a manual that goes into more detail on the rotational principles and practices of their weed control system. |

Anne & Eric Nordell’s System of Cover Cropping and Crop Rotations

By Jean English

In the early 1980s, when land was still “pretty cheap,” Eric and Anne Nordell bought their small farm in Trout Run, Pennsylvania – a place with steep, rugged terrain; a relatively short (for Pennsylvania) growing season; and no large, upscale markets nearby. A livestock operation would have been a good fit for this area, which does support numerous dairy farms, but that type of farming would have violated one of the Nordells’ three farming goals: to remain debt-free. So they decided to grow flowers, vegetables and herbs instead – crops that would enable them to meet their other two goals: to keep the farm a two-person operation, because they love working together; and to be able to depend on the internal resources of the farm as much as possible.

Eric and Anne explained, at the 2000 Farmer to Farmer Conference in Bar Harbor, that they realized they needed good weed control to keep Trout Run Farm a two-person operation, and they found that reducing the weed pressure before seeding crops – especially the poorly competitive root crops – ”could make all the difference.” Their lack of irrigation also demanded that they minimize competition from weeds for water.

Cool season crops soon became one of their specialties, because other farmers in the area were not growing them. They found that “packing a clean, quality product like leaf lettuce allowed us to get our feet in the door of restaurants” and other markets. At the Williamsport Farmers’ Market, their customers have “become so dedicated, they come out regardless of the weather.”

Success didn’t come overnight. Their farm was low in fertility and infested with quackgrass when they bought it. They used summer fallow to eliminate the quackgrass, a method they say is “applicable regardless of the size of the farm.” Anne learned about summer fallow when she worked on a large herb farm in Washington state, where the growers would bring the roots up with a chisel plow and let them dry out in the sun over and over during the summer. At Trout Run, she and Eric use a sweep, then a flexible pasture harrow, which shakes the soil off the roots so that they dry and die faster. The technique “is effective as long as you keep the quackgrass from greening, even if it doesn’t dry,” they said. Following the fallow period, they cover cropped the ground with rye in the fall. “It’s critical to use clean seed when cover cropping for weed control,” they said. Getting clean seed should not be a problem if you’re buying from a seed company, but the Nordells buy from nearby farmers, so they clean the seed themselves before sowing it.

The growers found the combination of bare fallow followed by rye to be so effective that they adopted it throughout their farm, year after year. They alternate half-acre fallow strips with half-acre strips of marketable crops, so 3 acres are always in crops and the other 3 are fallow or in cover crops. Over the years, they’ve been able to reduce the fallow period to six weeks or less as their weed population has diminished. They believe that maintaining suitable pH and calcium levels for crops in the soil also seems to favor the growth of crops over grasses.

|

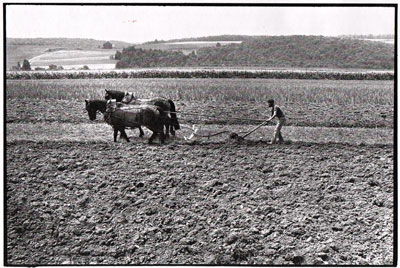

| The Nordells adapted the strip cropping rotational system used by dairy farmers in their part of Pennsylvania to a market garden situation. Photo by Earl Holden Jr. and Sr. |

Thus, the Nordells have substituted summer fallow and crop rotation for the time they would have spent weeding, freeing them to spend more time picking, packing and marketing. “We’re substituting land and live horsepower for off-farm inputs and labor,” they explained. [Their horse-drawn cultivation equipment is “very primitive,” Eric said.]

Two Cropping Sequences

They described two cropping sequences. In one, a late planted and harvested crop, such as potatoes, is followed by broadcasted winter hardy rye – the only cover crop that can get established that late in the year. The rye is mowed several times in the spring to encourage it to tiller and regrow. “This creates a nice mulch to smother weeds, but at the same time the rye is regrowing,” they said. The third cutting occurs around the end of June, when the rye is incorporated into the soil and the fallow period begins. This coincides with “the weakest point in the life stage of the weeds we’re trying to control,” such as quackgrass, lambsquarters, pigweed and others. “The objective is to clean the field of weeds a full year before planting cash crops.” The fallow period can be followed by a cover crop of Canadian field peas – or oats (both will be winterkilled). The pea or oat seeds are broadcast at higher rates than if they had been drilled, and are harrowed into the soil. In a garden, field peas are useful, said the Nordells, because they tend to rot at the base, so they’re easy to rake aside into the path when you want to plant in the spring.

The second sequence involves early crops that are removed by the end of July or early August. Sweet clover can be direct-seeded into the cash crops during the summer so that it becomes well established before winter. The following year, the sweet clover is mowed several times to prevent it from growing 4 or 5 feet tall, which would be too much growth to incorporate into the soil easily. Mowing also promotes increased root growth in the sweet clover and helps with weed control. The second clipping occurs around the fourth of July. After the clover is plowed down, the bare fallow period begins, with the soil being worked every two or three weeks. “It’s like a series of stale seed beds the year before the crops are planted,” said the Nordells. “You’re depleting the weed seed bank and putting weeds out of a job by using cover crops to build soil structure.” After the fallow period, rye and vetch can be grown, and 5 to 6 tons per acre of compost (from horse manure, straw and vegetable wastes) are applied to the plow-down area as well, to meet the needs of the heavy feeding crops that will follow.

|

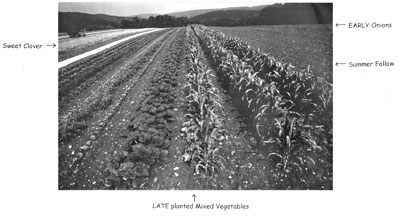

| Four beds show sweet clover; late planted mixed vegetables; summer fallow (for controlling quackgrass and other weeds); and early onions. Photo by John Nordell. |

The Nordells call their system “controlled rotational cover crops” and explain that they’re rotating the timing and types of cover crops. They’ve adapted the principles and practices that field crop farmers use to the market garden. “Old rotations almost always alternated between crops that were planted early and late,” the said. When starting such a system, they said that you may have to plow the fallow area in May and not seed it to cover crops until August. Once the quackgrass is under control, however, the bare fallow period will be just five or six weeks long – the same five or six weeks when broadleaf weeds are most troublesome and are best controlled. Sometimes they don’t even use a fallow period and go straight into a cash crop now. “It depends on how the weed pressure looks in the cover crop. Like any natural system, it’s constantly in flux.”

Adapting Traditional Field Crop Systems

During the second part of their talk, Eric and Anne elaborated on their rotational system. When they began farming in Pennsylvania, there was not much precedent for cover crop rotational systems in vegetables, so they looked at traditional field crop rotations for ideas. They learned about the COWS system: – Corn-Oats-Wheat-Sod – that was used in the Midwest and in Pennsylvania. The sod would be a grass-legume mixture. They noted how this system rotated more than just crops. By rotating in contoured strips of corn, oats, wheat and sod, erosion was minimized, because corn was the only row crop. Tillage was also rotated, as were planting dates. Labor was spread more evenly over the year also – a necessity when these types of rotations were developed, because animals supplied the labor. They have noticed that the farmers in their area have “a kind of rhythm of labor. The farmers near us get a lot done but never seem frantic.”

Eric diagrammed the COWS rotation as follows:

| Strip 1 | Strip 2 | Strip 3 | Strip 4 | |

| Spring | Sod | Oats | Wheat | |

| Summer | Sod | Corn | Clover (seeded into wheat in spring) | |

| Fall | Sod | Wheat |

He pointed out that corn, the heaviest feeder, follows almost two years of soil-building sod; that manure is usually applied before the sod is plowed in this system; and that the fertility of the whole farm system is being concentrated in the corn.

Eric translated the above table into a table of weed control:

| Strip 1 | Strip 2 | Strip 3 | Strip 4 |

| Mowing | Aggressive cultivation | Shading and summer fallow (control quackgrass) |

He then translated the system to a market garden:

| Strip 1 | Strip 2 | Strip 3 | Strip 4 | |

| Spring | Clover | Rye-vetch (apply compost | Rye plowdown midsummer | Early crop |

| Summer | Bare fallow | Late crop (heavy feeders) | Bare fallow | Seed clover |

| Fall | Rye-vetch | Rye | Small grain that winterkills (oats, peas) & apply compost |

The rotational system at Trout Run Farm is organized into 12 half-acre strips. Eric noted that during the fallow period, the soil can actually accumulate moisture, since no crops or weeds are present to transpire water. To minimize soil disturbance, they work the ground as shallowly as possible.

The Nordells talked about their new, no-till system of growing garlic. They adapted a subsoiler so that it makes slits in a cover crop of oats and peas. They plant garlic by hand into the slit, and the oats and peas die back over winter. In the spring, their no-till garlic came up two weeks earlier than garlic that had been heavily mulched and grown in the traditional manner.

|

| Rotating cover crops, summer fallow, early and late crops not only depletes the weed and weed seed reserves, it also spreads labor more uniformly over the season so that this team of horses – and the farmers – can be worked but not overworked. |

In addition to their 6-acre plot of vegetable and cover crops, the Nordells grow specialty crops – such as tomatoes, broccoli and culinary herbs – in their “house garden” using a similar rotation system. They noted that purslane sometimes grows in this garden and that it is “one of the trickier weeds” to control. A heavy mulch and a midsummer smother crop work better than bare fallow for this weed. Rye can be grown and cut several times to produce the mulch, they explained, and at the end of July, Canadian field peas or cow peas can be broadcast on top of the rye residue and then tilled in 2 to 3 inches deep (because of the heat).

Living mulches of sweet clover or white Dutch clover are overseeded into some cash crops to control erosion and build soil. They have also found that growing a single row of rye between cash crop rows, such as carrots, helps control erosion and doesn’t attract rodents as much as clovers do. Similarly, they have planted single rows of vetch between strawberry rows in June; the vetch dies back in the fall.

When asked whether they have a problem with the tarnished plant bug moving into crops when they mow sweet clover, they said that planting a row of buckwheat into the pathways of crops every two weeks provides a haven for beneficial insects (including honeybees), and that tarnished plant bugs move into the buckwheat rather than lettuce when they mow their sweet clover. “We have seen reduced damage from tarnished plant bug by doing this the last two or three years.”

The growing season is extended in the Nordells’ house garden by “porta-hoopies” that they built. They drilled holes into 4×4-inch sills, set the sills 12 feet apart, and drove 20-inch rebar into the holes in the sills, leaving 4 inches of rebar sticking up above the sill. They then slipped PVC pipe over the rebar to create a 12- x 60-foot hoop house for less than 200 dollars. “Because they’re portable,” Anne said, the porta-hoopies enable them to “use crop rotation and cover crops to bring weeds under control a full year ahead.”

When asked about their income, the growers said that they gross $30,000 to $40,000 per year; that about 10% of this goes to production costs; and that the net profit that they report to the IRS (after depreciation, etc.) is $15,000 to $16,000. They live a simple lifestyle and raise much of their own food.

The Nordells have made a video that shows their rotation system, and they have collected copies of the many superb articles they’ve written – about rotation, cultivation, growing onions, using pigs to turn compost, designing a barn for animals and for compost production, and more. The 52-minute tape ($10) and the collected articles ($10; postage and handling included) are available from Anne and Eric Nordell, RD 1 Box 205, Trout Run PA 17771. Their talks at farming conferences are superbly organized, illustrated and informative, as well, and they welcome feedback from growers who try their ideas.